Rough Riders

Five bushplanes and the places only they can fly.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Rough_Riders_11-01-11_1_FLASH.jpg)

They fly over mountains, into jungles and deserts, and onto lakes, making their way through remote places that can hardly be reached any other way. Bushplanes first took to the air after World War I to transport people and cargo to roadless areas, or to explore where most humans had never been. Today, these off-roaders of aviation provide disaster relief, ferry adventurers, and haul daily necessities to isolated communities. Their pilots have to contend with short, rough landing strips and animals straying into their paths on final approach. They land where there are no spare parts or emergency supplies. But to pilots that’s the appeal of bush flying: no two runs are quite the same.

1. Noorduyn Norseman

In 1935, Dutch aircraft designer Robert B.C. Noorduyn custom-built an airplane for pilot Hugh Carlson of Viking Outpost in northern Ontario, Canada. In truth, Carlson wouldn’t be born for another 12 years, but when Noorduyn created the airplane, he had a pilot like Carlson in mind.

Noorduyn, who had worked for Fokker, Bellanca, and Pitcairn, started his own company in 1933 to build an airplane ideal for the Canadian outback. To get it right, he asked bush pilots what they wanted.

For starters, they told him, the airplane should have high wings and four doors, two on each side (for ease in loading cargo and passengers). It had to be adaptable to floats, skis, or fixed landing gear. It needed the capability to carry large loads. It had to be strong enough to withstand rough water on lakes in summer or to plow through snowdrifts in winter. And for those endless winters, it needed an insulated cabin and heated cockpit.

The result: the Noorduyn Norseman. Though designed as a bushplane, the Norseman was widely used as a transport for the Allies during World War II. (Big band leader Glenn Miller was aboard one on assignment for the Army Air Forces band when he disappeared over the English Channel in 1944.) By the time production ended in 1959, a total of 903 Norsemen were built. Fewer than 50 are still flying, 37 of them registered in Canada.

Carlson, whose family has owned and operated a lodge on Red Lake, Ontario, for six decades, bought his Norseman in 1992, and uses it to ferry hunters and fishermen to remote camps. “It’s easy to load,” he says. “I can just sit in the back door and have people hand stuff to me.” Whatever doesn’t fit, such as canoes or lumber, can be strapped to the wing struts. With a balanced load, Carlson says, the airplane almost flies itself. “I’ve sat back, arms crossed, feet on the floor, and not touched the controls for as long as 17 minutes.”

The airplane’s nine-cylinder, 600-horsepower Pratt & Whitney radial engine rumbles like a gang of Harleys. It’s the same engine as that on the de Havilland Otter, but because the Norseman uses a direct drive to turn the propeller instead of a geared system, the engine has been more reliable on Noorduyn’s design. “They had a lot of engine failures,” Carlson says of the Otters, which is one reason those airplanes were converted to turbine-engine power.

Red Lake, about 280 miles north of International Falls, Minnesota, lies at an elevation of 1,200 feet. “You get 300 feet above that and you can fly for hundreds of miles in any direction and not hit a thing,” Carlson says. To land, all he has to do is pull back on the power about 10 miles from touchdown, “and as long as I don’t hit an island, it’s a perfect landing every time.” Carlson remembers flights on calm mornings, when the lakes gleamed like mirrors and he managed to land a planeload of sleeping passengers without waking any of them.

Carlson recently sold his Norseman. The airplane was due for a major overhaul and he figured he’d be retired before he’d be able to earn back the money the work would cost. The new owner stays in touch, and Carlson will be able to see his rugged old bird every summer during the annual Norseman fly-in at Red Lake. “I miss it because it was such an enjoyable plane to fly,” Carlson says. “It will make even a ham-fisted pilot like me look good.”

2. Quest Kodiak

Craig Hollander usually gets to the hangar at Juwata Airport in Tarakan, a city in East Kalimantan, Indonesia, at around 6:30 a.m. After a preflight check of his airplane, he gets the weather report called in from villages in the mountains. It’s always the same: low clouds, rain the night before, poor visibility. He knows if he waits until 8 to depart, the fog will begin to burn off during the hour-long flight from the coastal lowlands to the jungle interior. He also knows to head home by mid-afternoon to avoid the usual tropical thunderstorms.

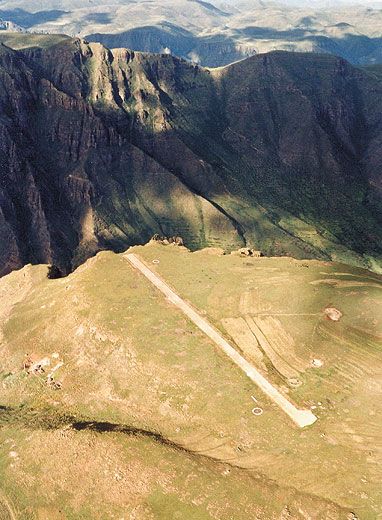

Hollander, who grew up in Ripon, California, flies for Mission Aviation Fellowship, a Christian missionary group dedicated to serving isolated people. Founded in 1945 by a group of World War II pilots, MAF has 126 aircraft in 24 countries for evangelical work, medical evacuation, disaster relief, and humanitarian assistance. In East Kalimantan, Hollander is one of 14 pilot-mechanics (MAF pilots have to be licensed mechanics) who serve more than two dozen villages in the province, an area about the size of the state of Georgia. With a fleet of four turbocharged Cessna 206s, a Cessna Caravan, and a Quest Kodiak, they fly in and out of strips carved out of the hills, with rough grass or dirt surfaces. Most are no longer than 1,500 feet, and nearly all are uphill with grades as high as 23 degrees. Landing approaches require the pilot to maneuver until turning to final about 50 feet above the ground and 150 yards from the runway.

“Having that slope is great for landing and takeoff,” Hollander says. “It gives you a little extra braking action on landing, and a little extra thrust on take-off.” After eight years flying in Indonesia, Hollander says he’s gotten so used to landing uphill that he has to adjust mentally when he lands on flat terrain.

The newest airplane to join the fleet is the Kodiak, one of a new generation of bushplanes. In fact, the manufacturer Quest was founded when more than a dozen missionary and humanitarian groups put up seed money to design and build an airplane to suit their needs.

The most persistent hazards Hollander faces are the conditions of the landing strips, and animals that stray onto them in the moments before touchdown. “We set abort points on every landing,” he says, “but after that point, if something runs out on the runway, you have to ask yourself if [it] is a threat to the plane. If it’s not, it’s better just to plow on through it.” Animal strikes to props and struts are common. “If you run into a chicken or a dog, there’s not going to be too much damage [to the airplane]. I’ve killed a number of dogs over the years. But that’s not too bad. The Indonesians eat dogs so they get a meal out of it.” But if a water buffalo is on the strip, “then you got some hard decisions to make,” he says. “If you hit a water buffalo at 50 knots that’s going to do some damage to both you and the water buffalo.”

The villages that Hollander serves are poor but not destitute, he says. Villagers can earn cash by collecting plants used in pharmaceuticals. MAF provides basic transportation, flying passengers and cargo—mail, construction supplies, food, fuel. The alternative would be a days- or weeks-long journey overland through dense rainforest or a dangerous excursion by boat down one of the swift rivers tumbling out of the mountains.

3. DHC Turbine Otter

Summer mornings in Talkeetna, Alaska, normally begin shrouded by a low, wet overcast. Talkeetna Air Taxi owner and pilot Paul Roderick knows the overcast will usually run solidly the 15 miles north to the Alaska Range foothills. So after filing a flight plan and loading passengers and gear into his de Havilland DHC-3T Turbine Otter, Roderick climbs above 8,000 feet, at which point the airplane breaks into the blue. Looming ahead is majestic Mount McKinley, North America’s highest peak and Roderick’s destination. Once he sees it, he cancels his instrument flight plan and heads for the 20,335-foot-tall mountain.

On McKinley, weather, wind, snow conditions, and visibility are all constantly in flux. “You have to go up there with a totally open mind, ready for anything,” says Roderick, who in addition to flying charters and sightseers around the mountain specializes in depositing climbers on glaciers or on narrow shelves at the bottom of cliffs.

“You may fly into a strip in the morning and there’ll be fresh snow and it will be cold and fast,” Roderick says. “Then the sun will work on it and by afternoon it will be heavy and sticky, almost like sandpaper.” Throw in a light snowfall or gusting winds and it gets challenging, he says.

Roderick has been mountain flying for 20 years. A native of Connecticut, he learned to fly at Embry-Riddle University in Prescott, Arizona, then moved to Alaska and got a job at the company he now owns. Back then, mountain operators only flew Cessna 185s. “It’s an efficient plane and it’s fast,” Roderick says of the ubiquitous six-seat, single-engine taildragger. While larger airplanes such as the de Havilland Beaver and Otter were doing bush work, glacier pilots thought those airplanes were too heavy and would get stuck in the snow. Also, the Pratt & Whitney radial engines on the Beaver and Otter needed babying. “You couldn’t jockey the throttle around,” Roderick says. “You could blow a jug [crack a cylinder] if you weren’t careful by shock-cooling the engine”—descending too quickly, which forces cold air over the hot metal.

All that changed with the Turbine Otter. Replacing the 600-hp piston radials with a 1,000-hp turbine made the airplane faster and more efficient. “With the turbines, you can be at 12,000 feet and just pull the throttle back and drop down 2,000 feet a minute into a glacial bowl and land,” Roderick says. “They have so much power with the turbine that they can just power their way through deep snow.” With room for 10 passengers and a 3,400-pound payload, what used to take two or three trips in a Cessna 185 can now be done with one in the Otter.

Nearly everything about glacier flying seems counter to conventional flying. In a lot of cases, you’re flying on final approach below your touchdown point. “You’re basically flying up the slope of the peak, trying to match the incline of the mountain,” Roderick says. “The thing about flying glaciers is things are always changing. There are a hundred types of snow. The weather, the winds, the light—it’s always changing. No two landings are the same.” Because of the possibility of weather closing in or of mechanical problems, every airplane carries food, sleeping bags, and survival equipment. “Inevitably,” Roderick says, “one of us gets stuck overnight on the mountain each season.”

4. Cessna

You don’t need a heavy-duty airplane for bush flying, says Karl Finatzer. Whatever you fly, “you just have to know how to fly it professionally.” To prove it, the founder of SkyAfrica uses a fleet of single-engine Cessnas (150, 172, and 182 variants) and a Piper Cherokee 235 for “flying safaris” that land and take off from unimproved strips all over the continent. Other than their distinctive, brightly colored paint jobs (“We got tired of white and lines,” Finatzer jokes), the airplanes are the same ubiquitous models that many pilots learned in or flew sometime in their career.

Which is exactly the point.

SkyAfrica invites pilots to travel to the company’s base, near Johannesburg, South Africa, rent its aircraft, and, after a short certification course plus some instruction on bush flying, take off into the wild, either in a group with a pilot-guide or on their own. The company plans the itinerary and arranges fuel, accommodations, border-crossing permits, ground transportation, and side trips. The flights offer a unique way to see and experience some of the most beautiful landscapes on Earth: deserts, jungles, mountains, river deltas, savannahs. “To see everything that we can show you in two weeks would take months by jeep or car,” Finatzer says. And all of it accessed from remote backcountry strips: grass, dirt, uphill, downhill.

Pilots landing on the 3,200-foot dirt strip at the Kunkuru game lodge in South Africa might find obstacles (hitting an anthill is like hitting a concrete post) and wildlife. Elephants aren’t a problem, Finatzer says. But a giraffe is fearless. You can buzz five feet over its head and it still won’t move. Most of the time, you’ll end up having to fly to another strip.

SkyAfrica has organized adventures from South Africa to Kenya, a distance of nearly 2,000 miles. But it is more than simply an air tourism company. It flies in supplies, flies out the sick, does surveying, and offers flying lessons—“a little bit of everything,” Finatzer says. But the flying safaris are closest to his heart. “When I started the business in 1981, it was just a way to pay for my flying addiction,” he says. Thirty years later, “it’s pretty much the same thing.”

5. P-750 XSTOL

It’s an airplane only a mother could love: Boxy, bug-eyed, with wings bent at an angle, and an extended snout of a nose, the Pacific Aerospace P-750 XSTOL looks a little like a flying anteater.

“It’s about the ugliest aircraft I’ve ever flown,” says Chris Briers, a pilot and manager with National Airways Corporation (NAC), a charter and service company based in Lanseria, South Africa, a suburb of Johannesburg. What it lacks in beauty, though, it makes up for in performance. “It’s rugged, easy, and safe to fly,” Briers says. “It’s very simple, cheap to maintain and run. I have 64 type ratings, and I can say this has become my favorite airplane to fly.”

Derived from the PAC Cresco, which was designed for cropdusting and hauling skydivers, the P-750 features an extended fuselage and modified tail. It is powered by the same Pratt & Whitney JT6A turbine used on the Quest Kodiak and the turbocharged de Havilland Otter. The P-750 can land and take off in less than 800 feet and carry more than 4,000 pounds.

“The most amazing aspect of it is the slow-flight capabilities and the docile stall characteristics of that wing,” Briers says.

With its three P-750s, the NAC has contracts to fly for the U.N. World Food Programme in Chad, Somalia, and Sudan. The airplanes ferry aid workers, fly in supplies, and provide medical evacuations in remote areas. Years of drought and civil strife have turned hundreds of thousands of people in the region into refugees. So the U.N. Humanitarian Air Services charters a wide variety of aircraft to fly in supplies, haul passengers and cargo, or provide transportation where none exists.

The terrain is mostly desert, with some rugged mountains. “Just about every strip we fly into is soft dirt or sand, which is why this aircraft is a such a favorite with the World Food Programme,” he says.

With a two-person crew, the P-750 can carry eight passengers, or a combination of people and freight. Because the areas where the aid organizations work would be unsafe for overnight stays, NAC delivers relief workers with their equipment each morning, and then flies them back to one of the main bases in the afternoon.

The conditions are harsh. Daytime temperatures can reach 115 degrees Fahrenheit. Dust storms are common, and security concerns can make some airstrips unusable or force a change of plans.

Like the places it goes, the P-750 doesn’t have a lot of amenities. “There’s been no attempt to doll it up,” Briers says. Bushplanes aren’t chosen for their looks.

Tom LeCompte wrote about deadstick landings in the Dec. 2009/Jan. 2010 issue of Air & Space/Smithsonian.