Saying Goodbye to My Seahawk

The day I had to leave my SH-60B helicopter at the boneyard.

:focal(492x208:493x209)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/64/a1641563-0382-4fc1-8b40-609019460656/17c_on2016_cimg0444_live.jpg)

We landed from a hover and taxied for what seemed like miles across the desert airfield. At last, the plane captain waved us to a stop, and we began the shutdown procedures for our Sikorsky SH-60B Seahawk. I held the controls while my copilot ran the checklist and flipped switches. He reached the step that reads “PCLs—Idle,” which directs the pilot to pull the power control levers aft, out of the “Fly” position.

“Killing One,” he said, indicating that he was securing the no. 1 engine. Poor word choice, I thought, as the turboshaft shut down. The Turbine Gas Temperature gauge on both engines ticked to zero, the helicopter’s heartbeat flatlining for good.

It was late November 2012, and, accompanied by another SH-60B due for decommissioning, we had reached the final stop on our cross-country flight: Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, home to the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group. Davis-Monthan is home to the largest military aircraft “boneyard” in the world, a usually-final resting place for more than 4,400 aircraft, including a relatively small number of civilian aircraft. This is Arlington Cemetery for faithful aircraft who have spent their lives in service to their nation. After three decades in salt spray and pitching waves, it seemed strange that these helicopters should end up in a dust bowl ringed by mountains. But it would be the final resting place for every SH-60B I had flown in my first three years as a Navy pilot.

The sudden absence of the rotor blades’ staccato roar made the silence in the cockpit feel somehow just as loud. In just a few seconds, the boneyard workers would surround the aircraft, inspect it carefully, and begin the preservation process. Some aircraft are marked for metal scrap, some are cannibalized for parts to keep other aircraft flying, others are marketed to foreign militaries. A lucky few even return to flight status.

I didn’t know my aircraft’s ultimate fate. I knew that within days, if not hours, it would be drained of all fluids and sealed with a white latex layer called Spraylat. I knew its rotor blades would be removed, giving it an appearance as unsettling to me as a headless Barbie. The lines of Earthbound aircraft made me think of broken toys.

Before unstrapping and climbing out, I reached for the rotary dial of the TACAN, or Tactical Air Navigation System. I clicked until the numbers read “51X”—the homing beacon channel for Naval Station Mayport in Jacksonville, Florida. Silly, but it made me feel better. Just in case this Seahawk ever needs to find its way home.

The Mayport squadron I joined in 2010 as a “nugget” aviator, HSL-46, sent detachments of six or seven pilots, 20-odd enlisted maintainers, and one or two helicopters to deploy on the Navy’s smallest boats. Most people assume Navy pilots deploy on aircraft carriers, but the world of the -60B was much more confined. The USS Anzio, a guided-missile cruiser and the largest class of the Navy’s small ships, is all of 567 feet long. We took two helicopters and stuffed them, blades and tail folded, in an afterthought of a hangar above the missile deck.

These Seahawks had been built in the mid-1980s in the Sikorsky factory at Stratford, Connecticut. Plaques stating each helicopter’s month and year of delivery were usually obscured by the copilot’s boots in the cockpit. The two aircraft being retired on this day had deployed many times, on cruisers, frigates, and destroyers, with many pilots.

Before 1993, only men had the privilege to fly them. Sixteen years after women were given the chance, I was assigned to a -60B in a training squadron, HSL-40. The helicopters that had hunted Soviet submarines during the cold war and stood watch in the waters off Kosovo were often nicknamed after pilots’ wives or girlfriends. By 2011, the helicopters were just as often named for reality TV celebrities or popular songs—my favorite was called “Crazy Bitch” after a hard rock song. (The helicopter dubbed “Kim” was named for Kim Kardashian, although this was not meant as a flattering tribute.)

I was among the last to fly the SH-60B. By the time of the official SH-60B Seahawk sundown ceremony in San Diego, about two and a half years later, all Navy helicopter squadrons would have transitioned to the MH-60R—also named Seahawk—which boasted an all-glass digital cockpit, among other enhancements.

Our two-aircraft formation had flown from Florida to Arizona in a four-day, three-night “road” trip. It was my first flight over land in more than half a year. After months of monochromatic blue beneath the aircraft, a change in scenery was revitalizing, and I soaked up the green bayou vistas of the Deep South, grateful to be back in the States. We refueled in landlocked cattle towns, where the concept of a seagoing service was as foreign as a Democrat. On our next-to-last day, after 12 hours of flying, we stopped in El Paso just after sunset and tied down the aircraft for the night, one leg short of our destination. We had been allowed three to five days to deliver the birds, with authority to deviate for weather or maintenance issues as long as we kept our squadron apprised of our progress. Without saying it out loud, all four pilots seemed to want to delay the inevitable parting.

The isolated world of a warship at sea can be claustrophobic, and even the most serious of missions felt like a reprieve from ship’s prison. We called it “air liberty”—flying low over the whitecaps, spotting dolphins in foreign waters, cloud surfing on lazy, quiet days in theater, and then the high-intensity night approaches to the rocking postage stamp of a flight deck. Our helicopters represented freedom, the way a teenager’s first car does.

Over two deployments I logged nearly 1,000 flight hours, and spent more than a year away from the States. My squadron changed in my absence, phasing in the new helicopters. New pilots, sharing the new-car smell of their advanced MH-60Rs, were my peers, sort of, but they made me feel like a dinosaur.

The military has a life-cycle plan for every war machine purchased, and the original intended life span of an SH-60B was 10,000 hours. When a replacement helicopter wasn’t quite ready, a paperwork drill extended the limit to 12,000 hours, then 13,000. To offset the extensions, the engineers at Naval Air Systems Command implemented a system called Fatigue Life Management, limiting flight time to 80 hours a month per aircraft. The -60B, dubbed a “legacy” helicopter as new ones rolled off the assembly line, were all I’d known, and the boneyard delivery offered me a chance to say goodbye before shore duty. I would continue flying in the MH-60R for a test squadron, but it wasn’t the same. I felt I owed the SH-60B a debt of gratitude, for my early flight lessons and for its years of service to many pilots before me.

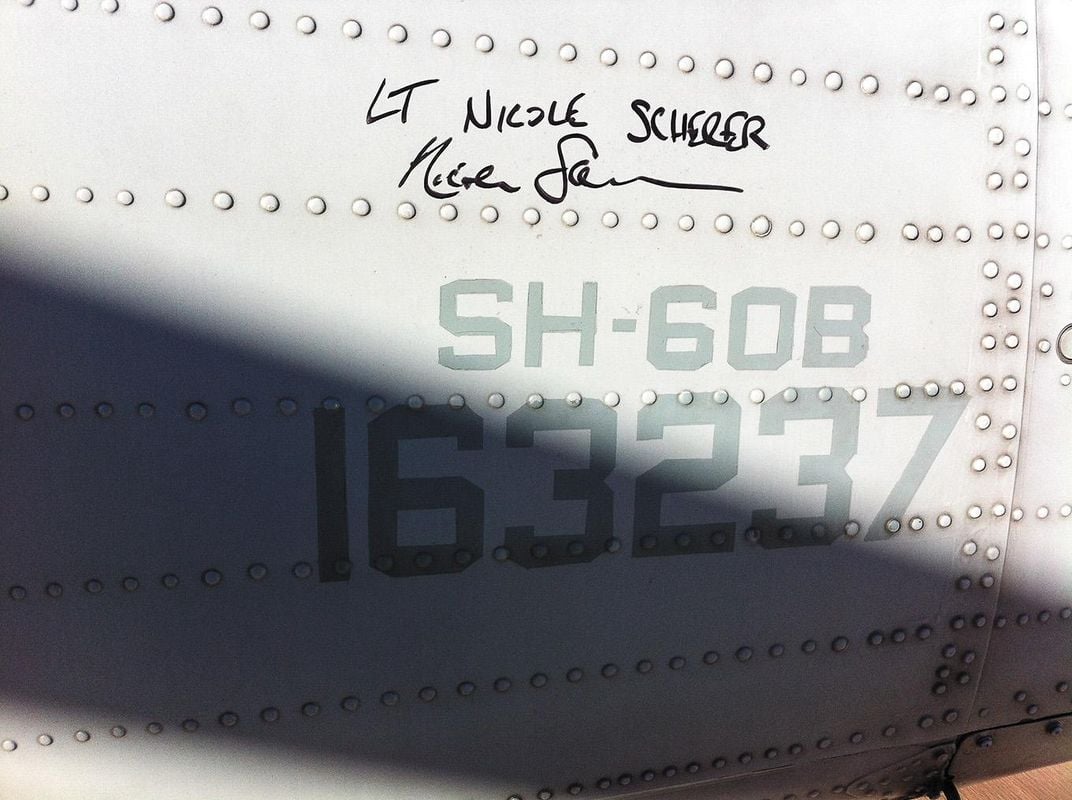

The boneyard workers handed Sharpies to the six aircrew so we could sign the tails of the two helicopters. As I signed, I recalled all the hours I had spent in a -60B, learning what it meant to be a Navy helicopter pilot. I signed a custody transfer release, and the boneyard crew offered a receipt. Unsure of what to do with a receipt for a multimillion-dollar helicopter, I folded it and stuffed it in the pocket of my flight suit.

I ran my hand across the helicopter’s rivets one last time, and walked away.