The Search for Luna 9

Fifty years later, researchers try to locate the first spacecraft to land on another world.

:focal(490x546:491x547)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d8/29/d82911ce-c650-4ead-aa3f-cf7d5bfed7a7/24k_sep2015_luna9_live_web_resize.jpg)

Earth’s moon is a cemetery of space probes, hurled there by numerous nations over the last half-century. Whether they landed successfully or crashed in a useless plume of lunar dust, we usually lost sight of them. NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), which has been scanning the moon’s surface since 2009, has been key to spotting some of these milestone spacecraft. It has sent back pictures of all six Apollo landing sites and that of Surveyor 1, NASA’s first moon lander, which went up in June 1966 to scope out the terrain ahead of the astronauts. Now the hunt is on for the coup de grâce of moon memorabilia.

On February 3, 1966, the Soviet Union kept its lead in the space race by successfully landing the first spacecraft on another celestial body. Luna 9, a spherical spacecraft about two feet in diameter, was ejected from its descent stage and rolled to a stop in Oceanus Procellarum, better known as the Ocean of Storms.

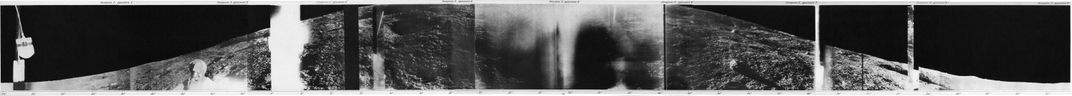

Luna 9 took the first up-close images of the moon’s landscape, which conveyed a vital piece of information: The lunar surface could support the weight of a lander. It wouldn’t gulp the hardware into a loose layer of dust, as some scientists had hypothesized. On February 6, the probe’s batteries died, ending the mission.

Now researchers are using LRO to find this historic spacecraft. Jeff Plescia, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, is one of the leading lunar detectives. He’s combing through the LRO images of the Ocean of Storms. “I have a large screen so that I can study the digital image, stretch it, and look for what might be of interest,” says Plescia.

Why is the search for Luna 9 so challenging? The spacecraft is just so tiny: “Its size is close to the resolution of the images,” Plescia says. By comparison, Surveyor 1, at 14 feet across and nearly 10 feet tall, practically looms in LRO images. Hunters might have better success looking for Luna 9’s discarded descent stage, Plescia says, which could have created a blast pattern nearby.

Also hungry to spot Luna 9 is Mark Robinson of Arizona State University, the principal investigator for LRO’s camera. He says that it’s not only Luna 9’s size but its history that makes the lander hard to find: It was one of the first spacecraft to make it to the moon. “We don’t have a before picture of the landing site,” he says. He’s looking for shadows the lander might cast in dawn and dusk images. Also, pictures snapped when the sun is at zenith, he says, might reveal a halo surrounding the lander.

Robinson hopes future explorers will be able to give Luna 9 the Surveyor 3 treatment: Apollo 12 astronauts landed nearby and brought Surveyor’s camera home; it’s now on display in the National Air and Space Museum.