Secret Casualties of the Cold War

Gary Powers wasn’t the only one. More than 200 airmen were shot down while spying on the Soviet Union.

:focal(2600x2925:2601x2926)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/87/d5/87d5ce57-b2da-4708-b0b4-79d119b56c22/04m_spypln2016_pb4y2privateer_live.jpg)

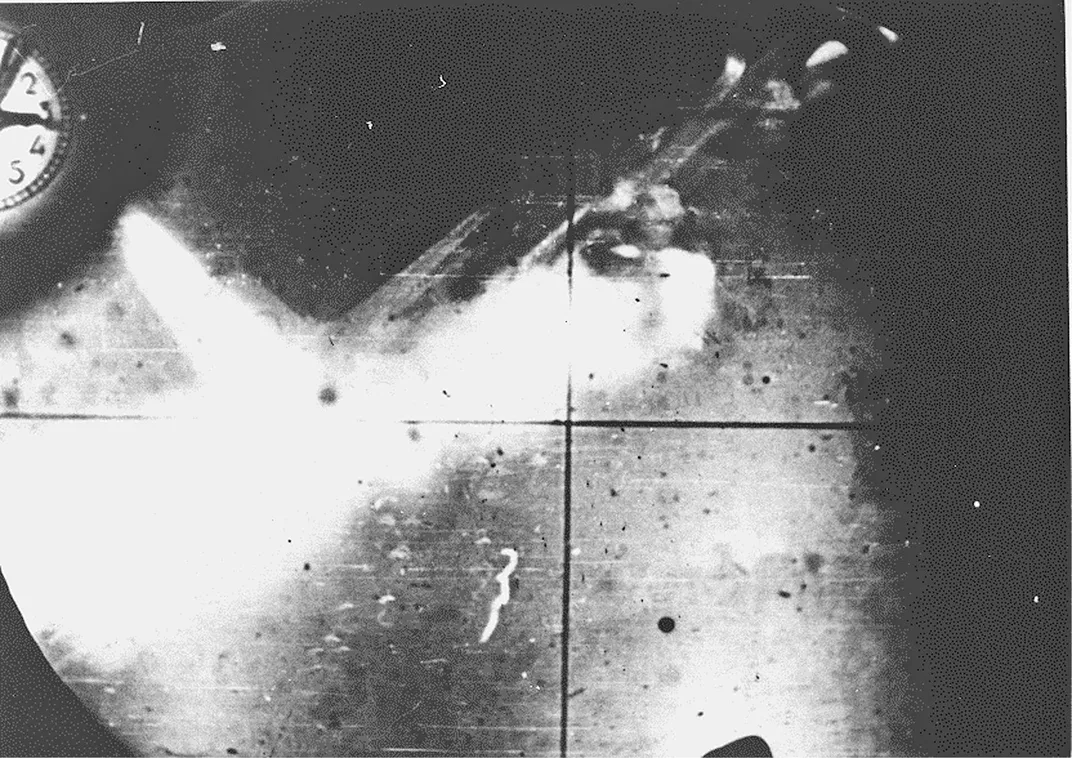

Near the gates of the National Security Agency at Fort Meade, Maryland, a C-130 Hercules sits in National Vigilance Park, on a small sliver of land sandwiched between a gas station and a parking lot. The aircraft is painted to represent Air Force 60528, which was shot down by four MiG-17s on September 2, 1958, after entering Soviet airspace. On the NSA website, a grainy gun-camera image from one of the MiGs shows the C-130 ablaze; it crashed 28 miles inside the Armenian border, and all 17 crew members were killed.

When the families of the victims were notified of the crash, they weren’t told of the crew’s actual mission—spying on the Soviets—or what happened to them. They were given a cover story of a routine mission gone awry. Although the Soviets denied shooting down the aircraft (they claimed it “fell” onto their territory), a few weeks after the crash, they returned the remains of six individuals. They provided no information about the other 11 crew members.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, a U.S. excavation team searched previously classified files for clues to what had happened to the rest of the crew. They visited the crash site in Sasnashen, Armenia, in 1993. Had the others survived the crash, and perhaps been taken prisoners of war? The team interviewed the MiG-17 pilot who shot down the C-130 and asked if he’d seen anyone bail out of the aircraft. He hadn’t. They asked other witnesses: No one had seen parachutes.

Team members interviewed a General Sozinov who was at the site minutes after the crash. He said the aircraft burned for eight hours; survivors were unlikely. When they visited the site, they found hundreds of skeletal fragments; with these, they were able to identify two other crew members. They concluded the others had died there as well. The remains were brought back to the United States, and on September 2, 1998, the families of Air Force 60528 gathered at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia for a burial with full military honors.

The case of Air Force 60528 is unusual—not because the U.S. government withheld the truth about its purpose for nearly 40 years, but because the crew members’ remains were ultimately recovered and returned, and their memories honored. For the crews of at least 30 other lost reconnaissance airplanes, there has been no recovery, no return, no ceremony.

The most famous spying mission flown during the cold war was the high-altitude flight of Francis Gary Powers, whose U-2 was brought down on May 1, 1960, by a Soviet surface-to-air missile. But hundreds of airmen were shot down. Almost all were flying missions to collect information about Soviet air defenses.

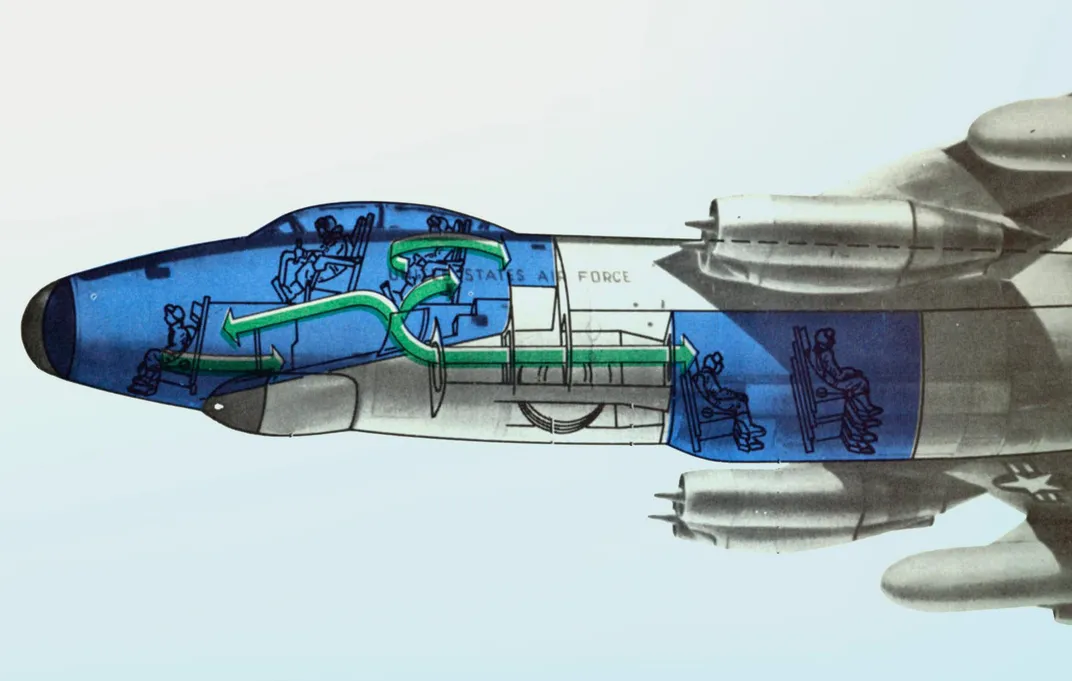

Ferret flights, as the reconnaissance missions had been nicknamed, dated back to World War II, when converted bombers carrying electronic equipment located enemy radar stations. Cold war ferret flights, made by the Navy and Air Force, had a similar purpose: pinpointing the location and capabilities of the enemy’s radar. In the event of nuclear war with the Soviet Union, the information would be critical to the U.S. Strategic Air Command bombers, which would have to jam, destroy, or evade radar in order to strike Soviet targets.

Flying unarmed and at night, along the Soviet borders or even hundreds of miles inland, the ferret crews did not try to hide from enemy radar; instead, they would get deliberately caught. Then they could listen to the enemy response through radio, radar, and other signals. The plan was to capture the information, then get out before fighters were scrambled or missiles were launched.

Often missions didn’t go according to plan. Carlos Campbell, an air intelligence officer who flew on reconnaissance flights in the early 1960s, told reporter William E. Burrows in 1994: “We were jumped by MiG-15s, MiG-17s, and ‘Flashlights’ [Yak‑25s] quite frequently. You go numb for about a second. Then you go into a reactive mode and loosen up. Anybody who tells you he isn’t scared isn’t breathing.”

Most aircraft flown on ferret flights, like the PB4Y-2 Privateer, the RB-50, and the RB-29, were variants of piston-powered World War II-era bombers, but some were newer jet aircraft. Surveillance crews were jammed into cramped compartments, where they huddled over radar screens and electronic monitoring devices. They were told that if they were shot down, they were on their own. They couldn’t expect rescue.

Because the ferret missions were top secret, the families knew nothing about the nature of the flights—or what happened when they went wrong. Finally, in 1992, documents about the flights were declassified. A joint U.S.-Russia commission was established to resolve cases, and families and private citizens doggedly undertook their own efforts to learn the fate of their loved ones. But 126 airmen are still unaccounted for. Their families are still waiting to find out what happened to them.

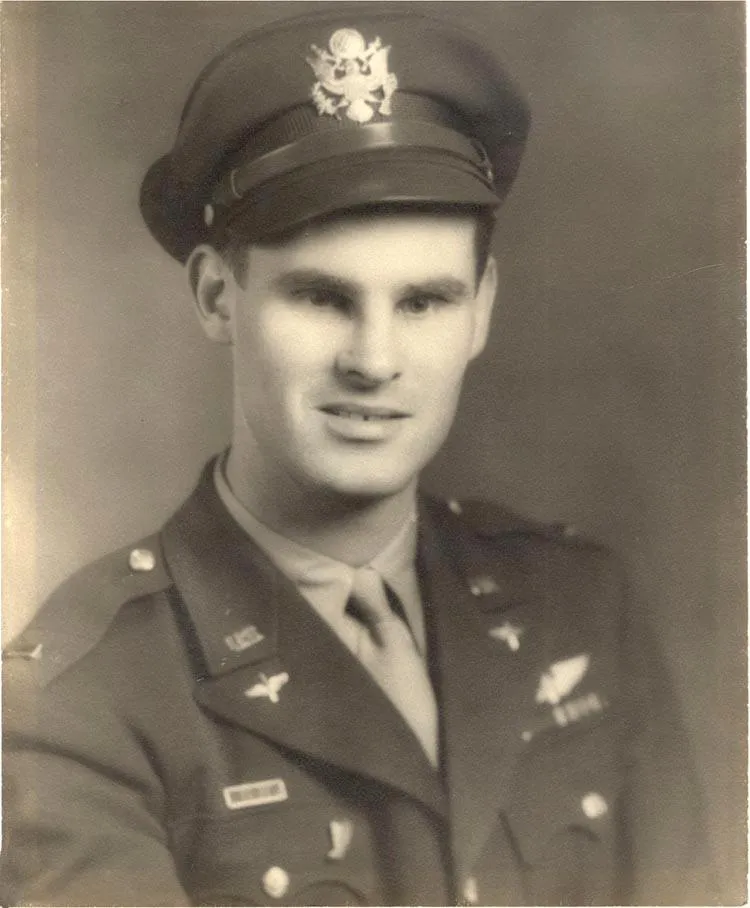

Jack Fette was the pilot of a Navy PB4Y-2 Privateer, a maritime patrol bomber converted to a ferret aircraft; his was based in Morocco. On April 8, 1950, just before Jack was due to go on leave, another Privateer pilot got sick. Jack volunteered to fly in his place. That night, he and the crew were shot down over the Baltic Sea. Jack’s sister, Dorothy Fette Neville, was waiting for a telegram to find out where to pick her brother up to begin his leave. Neville’s daughter, Kathy Fiffick, says today: “And [instead] she got the telegram that said the plane was lost.”

Charlotte Busch Mitnik has been waiting for her brother Sam since 1952. “You cannot mourn a POW/MIA,” she says. “What you do is you hope and you pray and you worry if they’re well, and wonder if they are ever coming home.”

In June 1952, Mitnik was 18 and had just graduated from high school. Her brother Sam was the pilot of an RB-29, converted from the famous four-engine Superfortress, stationed in Japan. “I was upstairs and I heard my dad close the window in the living room,” she recalls. “And then all of a sudden I heard my mother crying. I knew something tragic had happened to my brother.” For Charlotte’s family, this wasn’t a new experience: Charlotte’s brother Morris was lost in World War II.

Mitnik recalls her father frequently writing to senators asking for help, but nothing came of it. And that was the end of the story—for 40 years.

In 1992, Boris Yeltsin, the newly elected president of the Russian Federation, flew to a summit in Washington, D.C. On the airplane, he was interviewed by NBC News, and asked about American POWs from the Vietnam War. “Our archives have shown that it is true: Some of them were transferred to the territory of the former U.S.S.R. and were kept in labor camps,” Yeltsin said. A few days later, in a speech to a joint meeting of Congress, Yeltsin said that if any Americans were still in the former Soviet Union, they would be found and returned to their families.

A few months earlier, Yeltsin and President George H.W. Bush had formed the U.S.-Russia Joint Commission on POWs/MIAs to resolve outstanding cases, and ambassador Malcolm Toon was sent to Moscow to make initial inquiries. Although the trip was not productive, the previously chilly relations seemed to thaw. “There was the sense that the Russians were ready to work with us,” says Norman Kass, the executive secretary of the U.S. side of the commission from 1993 to 2010. Kass felt “a sense of optimism that we’ve gotten past all the strain and conflict of the cold war, and here we had decided on working together on a shared humanitarian interest. So it was about as hopeful a period as I can recall.”

Toon represented the Americans. General Dimitrii Volkogonov represented the Russians. As Yeltsin’s military adviser, he had access to records, and he had clout. Kass remembers seeing Volkogonov as “a ray of hope…who genuinely wanted to work through this issue.” Another ally on the Russian side was retired Admiral Boris Novyy, who doggedly pursued leads. “He still had access to materials that were deemed closed to any foreigners,” Kass says. “Working through him, we were able to make some headway.” Novyy supplied a large number of papers documenting “border violations” by U.S. reconnaissance aircraft.

The U.S. point man in Moscow was James Connell, a Naval Academy graduate with a Ph.D. in Russian and decades in the Navy working on Soviet issues, including the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. Connell, deputy chief of POWs/MIAs in Moscow, arrived in that city in 1992 with Toon: “I came for nine days and stayed for nine years,” he says.

Connell, who speaks with a quiet intensity, faced a daunting task. He and his team criss-crossed Russia and the former Soviet republics digging into archives. “There is not a big old folder somewhere that says ‘American POWs,’ unfortunately,” he says. “There’s the archives of the Russian Navy in Gatchina near St. Petersburg. There is Podolsk, which is the central archives of the Russian Ministry of Defense and has everything but the Navy [missions]. There’s the FSB and KGB archives. There is the Ministry of Foreign Affairs archives. Then you have the Archives of the Russian Federation. There’s a whole list of them.”

Connell and his team interviewed hundreds of witnesses: guards, retired officers, former prison camp inmates, even the pilots who shot down some of the airplanes. “A lot of our business is rumors,” Connell says, and tracking and corroborating the stories with the evidence is laborious. To investigate the case of Jack Fette’s Privateer, he says, “we’ve interviewed dozens of witnesses.”

He learned that Soviet rescue vessels were at the site of the Privateer’s crash within hours. While they didn’t find any aircraft wreckage, they did discover two inflated life rafts. In 1993, the commission interviewed Anatoly Gerasimov, one of the Russian pilots who intercepted the Privateer. He claimed the aircraft exploded mid-air before crashing into the sea. But in a documentary filmed just a few years after he spoke to the commission, Gerasimov said he’d seen 10 parachutes bailing out of the damaged aircraft—and that he’d been instructed not to tell the commission of this.

By now, witnesses have aged, adding urgency to the mission. Connell learned the name of one of the pilots who shot down the RB-29 piloted by Sam Busch, Charlotte’s brother. Connell went to Nalchik, near Chechnya, to interview the pilot, only to learn he’d died just two months before.

Informing the commission’s search was an unexpected trove of documents. In November 1992, archivist Richard Boylan at the Federal Records Center, just outside Washington, D.C., came across 35 boxes of files sealed since 1963. The files had been assembled by Sam Klaus, a long-forgotten state department lawyer with a top-secret security clearance who had hounded military and intelligence officials for documentation on what were then called “serious air incidents.” He amassed files on all the ferret missions up to that time so he could appeal to the International Court of Justice, forcing the Soviets to reveal what happened to the crews. The files provided Boylan with detailed information about what the U.S. government knew or speculated about the shootdowns.

In 1993, the commission’s Cold War Group scored an early success. A retired KGB Maritime Border Guards sailor, Vasili Saiko, presented the commission with a U.S. Naval Academy ring engraved with the name John Robertson Dunham, class of 1950. Dunham’s airplane, an RB-29 from the 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron, was shot down on October 7, 1952, over the Sea of Japan. Saiko said he’d found Dunham’s body, taken the ring, and buried the airman on Yuri Island. Dunham’s remains were excavated in September 1994 and returned to the United States. He was buried at Arlington in August 1995, and a month later, the RB-29 families gathered there to dedicate a stone memorializing the crew.

The commission’s research was reported to family members at regular meetings sponsored by the Department of Defense. Jack Fette’s niece Kathy Fiffick and her husband Paul started attending the meetings in 1996. Paul remembers hearing a rumor that Fette’s airplane had been salvaged. “[T]hey claim that this plane was raised by the Russians, and that when they pulled it up, someone on the salvage ship observed…two people still strapped into their seats,” he says. But Kathy also remembers their analysis: “The POW/MIA people told us about this. We heard about it when we went to one of the meetings. Then they told us it couldn’t be verified.”

That cycle would repeat. A rumor surfaces, sometimes with fragmentary evidence, is investigated, and is officially suspended into a state of the merely possible, along with words the families have come to dread: “There is not enough evidence to support that claim.”

The clues that surfaced about Sam Busch’s RB-29 mission show how families have been led to hope for understanding, only to be left with more mysteries. On June 13, 1952, Busch and his crew left Yokota Air Base, in Honshu, Japan, on a classified mission surveilling shipping activity in the Sea of Japan. Radar contact was lost three hours later, and the aircraft failed to return to base. During a rescue flight, an empty life raft was spotted about 100 miles off the Soviet coast, although no aircraft wreckage was found, and no survivors were sighted. It wasn’t until 1993 that the Russians released a 1952 memo to Soviet leader Joseph Stalin reporting that on June 13, a U.S. B-29 was shot down 18 miles from the shore. In the summer of 1999, Kass interviewed a Soviet émigré to Israel, Benjamin Dodin. A survivor of Soviet prison camps, Dodin had earlier presented his memoirs to the U.S. consulate; excerpts from his diary suggest that between four and 10 members of Busch’s crew survived the crash. The document includes two names: “Bush” (misspelled) and “Moore.” One of Sam Busch’s crewmates was Master Sergeant David Moore. Connell recalls, “At our request, the Russian Federal Security Service studied these memoirs and concluded they were without foundation in reality.”

But there’s more: Connell says that another RB-29 was shot down over China on July 4, 1952, less than a month after Busch’s was. During interrogation, a crewman on the July flight was asked about pilot Sam Busch. How would they know about Busch?

Charlotte Busch Mitnik says, “Some people in the Department of Defense said that they couldn’t verify the diary. But in my mind, I know that Dodin was telling the truth.”

After the initial successes—identifying the fate of 19 people—the commission’s effectiveness began to wane. When Volkogonov, the influential Russian chair, died in 1995, Kass lost a powerful ally: “[Volkogonov’s replacement] had nowhere near the clout and authority, and so the whole project, just from that transfer of authority, began to wane.” Admiral Novyy, deeply respected by the families for his steadfast searching, died in 2014.

Politics have played a major role in impeding the commission’s progress. In 2001, Connell and 49 other diplomats were kicked out of the country in retaliation for Russian diplomats being sent home from Washington for allegedly spying. In 2004, President Vladimir Putin dissolved the Russian side of the commission, and soon after shut down access to the main archive in Podolsk. The commission was eventually restarted, but Kass describes its present work as piecemeal.

The U.S. side has had its own problems. The Pentagon had two POW/MIA offices, and the commission operated independently of those. One of the offices, the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC), was roiled by press reports in 2013 of gross dysfunction. The two offices were merged into one unit, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), which began operations in early 2015.

At the agency’s annual meetings for POW/MIA families, Kathy Fiffick saw evidence of the complicated bureaucracy and lack of progress. “They always had some kind of information for us, even if it was just ‘We have applied to get into these archives. We’re trying to get the border patrol records,’ ” she recalls, “but that was it.” Despite their admiration and appreciation for the likes of Connell, Kass, and Novyy, the families interviewed for this article all perceive the agency as plagued by indifference.

“It got to the point where we ended up just scheduling meetings with Dr. Connell and Admiral Novyy, or whoever was around, and we would show up for that,” Fiffick says. “[But the officers assigned to us] wouldn’t know us from one year to the next. They were new every year.” In an email she makes her feelings very clear: “We do not think DPAA thinks it is worth any real effort given such a small number of Cold War [missing] in Russia. We do not expect that they will uncover any information for us in the future.”

The search for the cold war missing has been fueled by the initiative of individuals, whether under official government auspices or as independent citizens. Mark Sauter, an independent historian, took up the story in 1989. In the 1980s he commanded a U.S. guardpost inside the Korean DMZ and, following his service, became an investigative television reporter covering the military. His first breakthrough was at the Eisenhower Presidential Library in Abilene, Kansas, where he discovered a document from 1955 with the subject line “Re: POWs in the USSR.” Sauter’s curiosity was piqued.

Nearly 30 years later, after hundreds of Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, interviews with family members and Pentagon insiders, and travel to Moscow and Pyongyang, Sauter believes that crews could have been taken alive and imprisoned and that the U.S. government concealed that possibility. At the Eisenhower library, he found a declassified memo from January 1955 describing Soviet defector Yuri Rastvorov’s brief to U.S. officials on American POWs from Korea being held in Siberia. Another declassified memo, from General G.B. Erskine in the defense department to Walter Robertson in the state department in September 1955, states: “a small number of Air Force crews whose missions involved flights over the Sea of Japan during the Korean War were shot down by aircraft based in the Soviet Far East, some of whom are probably held by the Soviet Union.” The memo concludes by reminding the recipient of “the undesirability of providing any information through any source which might lead the next of kin…to assume or believe that these personnel might still be alive and held unless the Communists are prepared at some point to document such information.”

Several family members interviewed for this article refer to Sauter as a trusted resource. He has published his findings in two books, most recently American Trophies, co-authored with John Zimmerlee and published in 2013. His first book, Soldiers of Misfortune, changed Beverly Billinger Deane’s life.

In August 1956, Beverly was a 24-year-old whose husband of three months, Lieutenant James Brayton Deane Jr., was a pilot in the Navy’s VQ-1 Air Reconnaissance Squadron. She had put her medical studies on hold to move with Deane when he was deployed to Iwakuni Naval Air Station in Japan. On August 23, she opened her front door to find the squadron’s executive officer and a chaplain: Deane’s P4M-1Q Mercator was missing off the coast of Shanghai.

By 1992, Beverly had long accepted the official story: that her husband and his crew had been shot down and killed on a training mission. She had remarried in 1960, had four children, and moved on with her life. But upon reading Sauter’s book, she launched a 24-year quest for her possibly still living first husband.

Sauter wrote that Deane’s crew of 16 was tracked by Chinese radar for nearly 45 minutes before the aircraft was shot down over Chinese territorial waters. He also said U.S. intelligence officials had received reports for at least two years concerning the alleged survival of two members of the crew. Beverly read the Klaus files, finding documents confirming what Sauter had written. She got other documents through FOIA requests. One document said that one of the crash survivors had slightly raised cheekbones and thin lips, and that the intelligence officer felt the description fit Deane. She tracked down Deane’s former squadron mates, and sought records from dozens of military and government agencies. She went to China in 1999 and 2000, working through the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries. Li Xiaolin, the association’s vice president, told her that the Chinese government still considered the Deane files “highly classified.” At the end of her first trip, a Chinese acquaintance (whom she’d rather not name) told her that the previous year, a retired Chinese air force official had related an account—highly detailed—of a huge celebration held after the two pilots from the shootdown were captured. When Beverly returned to China in 2000, her acquaintance told her that the air force official was now describing his memory as “fuzzy”—and would talk to her only if government officials were present.

Beverly hit a wall and couldn’t break through. She even tried a card no other family had to play: She was a friend of Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. Rumsfeld and Deane had been in flight training together in Pensacola in 1954 and had become friends. Beverly asked for Rumsfeld’s help. He secured letters to the Chinese from President Ford and Henry Kissinger. Colin Powell made inquiries in 2001. Later, as George W. Bush’s Secretary of Defense, Rumsfeld himself made personal inquiries.

None of it made a difference. The Chinese simply refused to allow access to any files. Desperate, Beverly enlisted her daughter Katherine Shaver, a Washington Post reporter. Katherine chased the same trap lines and tried new contacts in China—all without result. She finally met with a courteous, stonewalling official at the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C., who repeated over and over that there were no records of survivors, and that was that.

“As a journalist, it’s extremely frustrating to know there’s information out there and you can’t get to it,” Katherine said in 2016. “As her daughter, it’s infuriating. She’s 83 years old, this happened 60 years ago, and she deserves an answer.”

It’s the same wall the researchers hit in Russia: files that remain sealed. Connell says, “There is a great deal of information we believe left in Russian archives, and we are going to fight to get access to all of it that we possibly can. When we have periodic meetings and sit across the table from one another and we tell them what we would like, they tell us either they can do it, or more often than not, ‘We’ll look into it,’ which is the standard answer.”

Connell and Kass see resistance on the U.S. side too. “For us it wasn’t the question of having [access] to look at the material, it was that the material could not be tracked down,” Kass says. “So that right away invites a whole slew of questions. ‘Well, how many other documents that could be helpful to our work have likewise not been made available or lost?’ ”

Before Kass retired in 2010, he and his team formulated a comprehensive plan for progress with the Russians. “We sent it to Moscow, the Russians agreed with it, and [six years later], it’s never been implemented,” he says.

Those still searching and waiting are in a race against the clock. Russia and China have very few cold war veterans left to interview. Charlotte Mitnik knows her time is limited too. “I’m 82 years old, and before I go, I would like to have my brother’s remains returned,” she said in 2016, adding, “I don’t think it will happen in my lifetime. How long has it been? Sixty-four years? They should still come out with some kind of facts.”

In Lepaja, Latvia, there is a rare example of official recognition of one of the shootdowns. Initiated in 2000, an annual ceremony at the Mother Sea Monument commemorates the downing of Jack Fette’s Privateer and the loss of the crew. Two commemorative plaques are also embedded in the monument. In 2015 Kathy and Paul Fiffick attended the ceremony, the first crew members’ family to do so. “They pulled out all the stops,” says Kathy. Paul recalls the moving speeches by the Latvians. “They always looked at the aircrew as a model,” he says. “Someday if [the Latvians] persisted, they would gain their independence from the Soviets.”

Later in the ceremony, on a ship on the Black Sea, the Fifficks and their hosts put four commemorative wreaths over the side. Kathy had a quiet moment to herself. “I was hoping that Jack was going to speak to me at one of those moments. I really hoped. I thought, ‘Maybe I’ll get one of those little miracles.’ I didn’t.”