The Secret Mosquito Stash

When Airbus tried to demolish a building, it uncovered treasure.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/d9/ded9779a-a2b3-444c-89f4-4aa506638e2d/24i_dj2018_si-72-8523_live-wr.jpg)

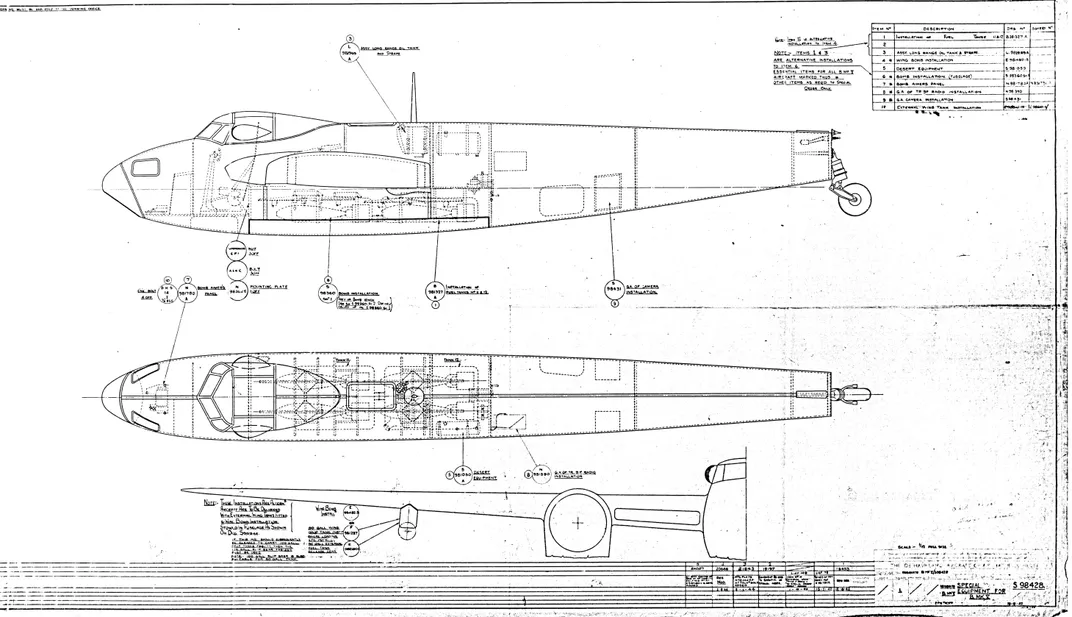

When Airbus Industries prepared to bulldoze a small World War II-era building at its Broughton, England facility last August, the crew found something astonishing: thousands of forgotten 80-year-old technical drawings for the de Havilland Mosquito, at one time the fastest aircraft in the world. Demolition was halted while Airbus contacted The People’s Mosquito, a U.K. charity hoping to restore and fly a version of the Royal Air Force’s versatile twin-engine bomber, and asked if they’d be interested in the documents.

John Lilley, chairman of The People’s Mosquito, immediately drove to the site. “When he got there,” says Ross Sharp, the charity’s director of engineering and airframe compliance, “he found himself staring at a filing cabinet full of more than 22,000 aperture cards.” (An aperture card is a microfilm image mounted on stiff card stock.) “It was an emergency situation,” Sharp continues, “so they put the cards—all 148 pounds of them—into refuse bags and loaded them into his car.”

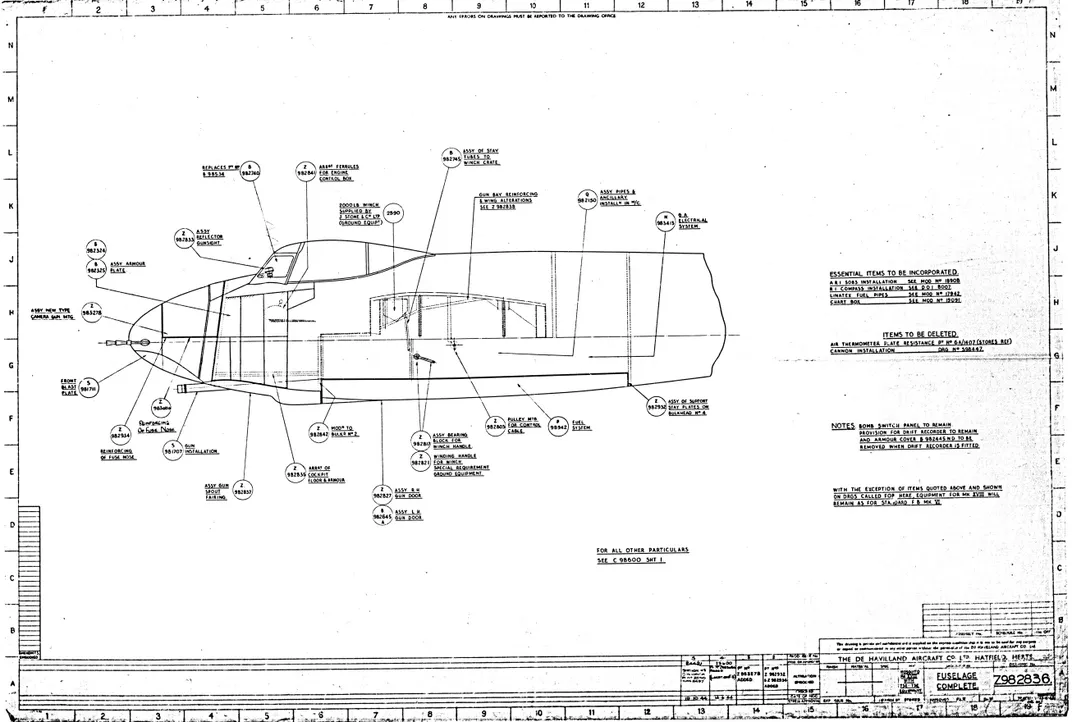

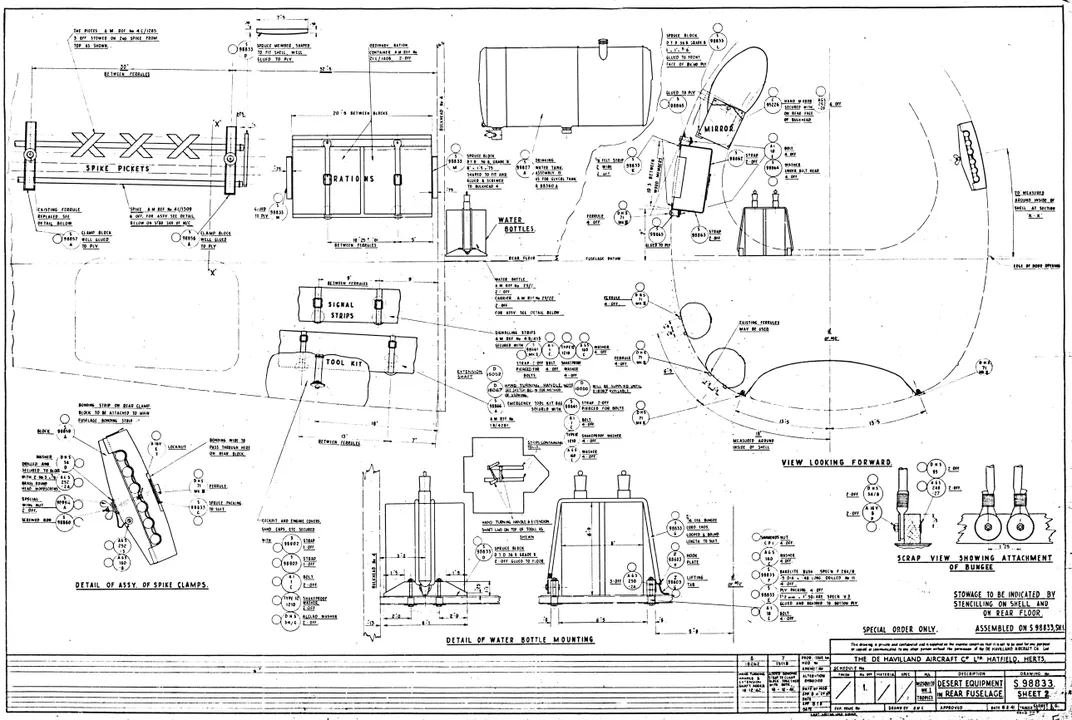

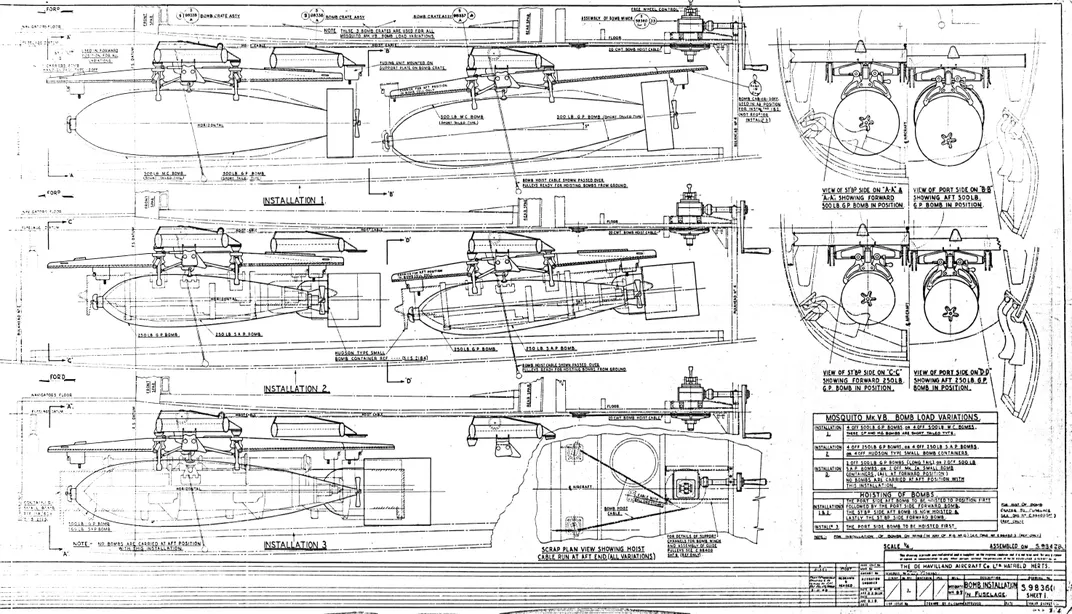

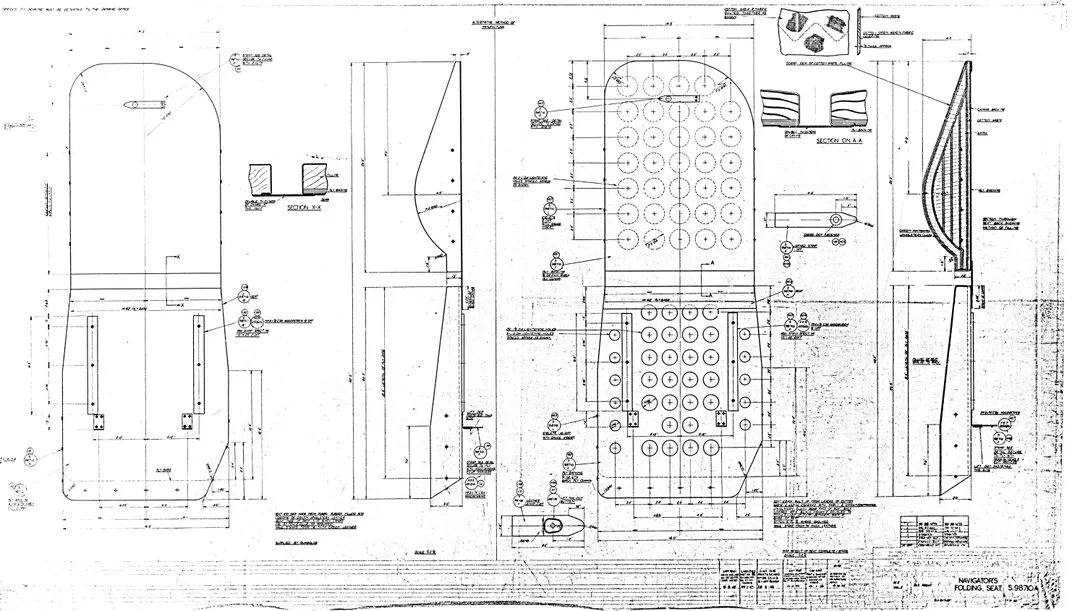

The cards, some in need of restoration themselves, were immediately scanned, at a cost of about $6,000. Sharp’s job is to assess their relevance; he is almost halfway through the collection. “Some of these drawings have an ethereal beauty,” he says, “although they contain much more than drawings, in that some include scribbled notes and rough sketches. Some of the cards contain annotations, things like ‘first two prototypes only.’ You are actually looking at a complete history of an aircraft, its evolution and its variants, including unbuilt versions.”

It makes sense that the documents were found at the Airbus facility; it was a de Havilland factory during the war, but much more recently serviced British Aerospace’s DH.98 Mosquito—the last airworthy Mosquito in all of Europe—until its crash at the Barton airshow in 1996. The documents are a mix of British Aerospace, Hawker Siddeley (the predecessor to British Aerospace) and de Havilland drawings, making classification a challenge. “I opened up one the other day,” says Sharp, “and I thought Wait a minute! That’s not a Mosquito—unless we suddenly started building a biplane version. It was actually specifications on how to completely re-cover, with Irish linen, a de Havilland Tiger Moth. The drawing just snuck in there.”

The drawings will help the organization in its restoration of a Mosquito NF.36 that crashed near RAF Coltishall airfield in February 1949. Instead of having to reverse-engineer parts of the bomber—a time-consuming and costly process—they can simply get the specs for the parts from the drawings.

“Things like the main hydraulic reservoir, that stands out,” says Sharp. “And we now have drawings for the internal baffles for the main fuel tanks. And there are minor things, like how to construct the navigator’s folding seat, its precise layout and the actual cotton and wadding that you use. It’s rather elegant.” The cost of the restoration is estimated at $9 million; if the entire funding were in place, says Sharp, the aircraft could be completed in about three and a half years.

Restoration has already begun; Aerowood Ltd., an aviation wood specialist in New Zealand, has started production on the aircraft’s wing ribs, using Canadian spruce cut from the same area—Queen Charlotte Islands—that generated lumber for wartime Mosquitoes produced by de Havilland Canada. During the war, 900 men—“former wrestlers, boxers, and local tough guys,” reported the Hartford Courant in 1943—worked 10-hour days cutting spruce trees for airplane production. “There are six main woods used in the Mosquito,” says Sharp, “all engineered, brilliantly, for what they do. Only one in 10 spruce trees were actually capable of meeting the exacting specifications for the aircraft.”

The airplane, known as the “Wooden Wonder” was originally built to be an unarmed fast bomber, but proved so versatile it was used as a night fighter, for photo-reconnaissance, as a light bomber, and as a maritime strike aircraft. Of the more than 7,000 Mosquitoes built, only a handful remain, and only three known airworthy examples survive, two in the United States, and one in Canada. The discovery of these priceless drawings has galvanized the members of The People’s Mosquito, who hope to see the aircraft once again flying over Britain. “We must fly and we must educate and we must remember,” says Sharp, “and honor all of those who have served in the Mosquito, including those that built her. And that’s just what we’re doing.”