She Just Wanted to Fly

A combat rescue pilot saved lives in Afghanistan while facing challenges to serve at home.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4a/17/4a17cb6a-8382-4fa8-a397-9cde3abbd411/mary_jennings_hegar.jpg)

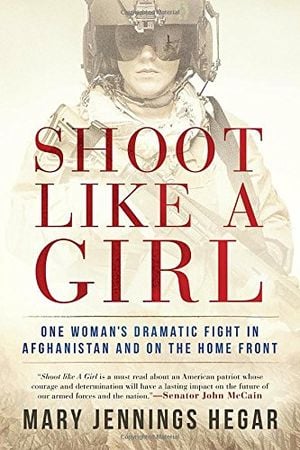

Mary Jennings “MJ” Hegar is a decorated veteran who served three tours in Afghanistan as a combat search-and-rescue pilot in the Air National Guard. She has written a moving account of her military experience and her fight against gender discrimination in the armed services in Shoot Like a Girl: One Woman’s Dramatic Fight in Afghanistan and on the Home Front. TriStar Pictures has secured the film rights to Hegar’s story. She spoke with Senior Associate Editor Diane Tedeschi.

Air & Space: Why did you decide to write this book?

Hegar: Initially, I wanted to educate people about Air Force combat rescue in Afghanistan. Unfortunately, that book didn’t get published, and my agent advised me that I needed to write more of a memoir—bringing attention to rescue through my own personal story instead of from a distance. As a private person and an introvert, this was a daunting task, but she was right. It’s the personal stories that seem to grab people’s attention. The women-in-combat theme is actually secondary and not very prevalent throughout the book. It’s not really even a book about a female pilot: It’s just a book about a pilot in Afghanistan, and the road she traveled to get there.

When did you decide that you wanted to be a military pilot?

When I was little and watched Han Solo evade the imperial fleet in the Millennium Falcon [in Star Wars], I wanted whatever career could get me closest to that asteroid field. A love of the freedom of flight mixed with an adrenaline addiction and a healthy dose of patriotism made flying rescue helicopters a natural choice.

What are some of the qualities that make a good combat-search-and-rescue (CSAR) helicopter pilot?

Aside from the qualities that make a good pilot in general—steely nerves, good hands, strong study/work ethic—I believe that, given the fact that we are maneuvering at high speeds very low to the ground often with live fire and lives depending on us, a good CSAR pilot must not be a cowboy—taking unnecessary risks to show off—and must be prepared to live the rescue motto of “These things we do that others may live.” There is a humility and sense of sacrifice that is critical to that motto that each of us must embody in order to be a true CSAR crew member.

Did your ROTC experience prepare you for the discrimination you faced as a female officer?

Honestly, it was a complete shock. I had one instance in high school, but other than that I never was the target of gender discrimination. I had setbacks, but they were due to my own mistakes. It was a shock due to the fact that my parents never made me feel like there was anything weird about my aspirations, despite the fact that, at the time, women actually weren’t allowed into combat cockpits. Being raised in a tolerant, progressive town like Austin [Texas] didn’t hurt either. So I was completely disarmed and caught unprepared to deal with the discrimination I faced after college.

After returning from a combat zone, was it sometimes difficult to transition to normal life back in the United States?

Absolutely. After you’ve cleaned American blood out of the back of your aircraft, it’s difficult to empathize with a family member complaining about the long line at the grocery store. Some people report having difficulty dealing with the fact that life went on for their loved ones back home—the world didn’t fall apart without them. I didn’t experience this, because I was single, but I understand the sentiment. For me, it was about trying not to punish people for the fact that they lived sheltered lives. It was also difficult coming down from the adrenaline and camaraderie [of a deployment].

Women serving in the military don’t want their gender to be a hindrance—or even an issue that requires special consideration. Do you think that day is coming sooner—or later?

I think that day gets closer and closer every minute. The more level the playing field, the more standards that are the same, the more competent women we get in these jobs, and the fewer instances where we have to make a point of someone’s gender—for job placement or lodging—the better off we’ll be.

Do you have any advice for women who want to serve in the armed forces?

Yes, I always tell people it’s a great idea to serve. Even if it turns out that it’s not for you, you have marketable experience, training, resources, and an assumption by employers that you have integrity, are a hard worker, and are coachable.

For women specifically, my advice is the same for women in any male-dominated career field. The best way to get ahead is to be the absolute best at whatever your job is. It’s the only way to be above reproach. Never assume that you’re being discriminated against. Always assume, first, that it’s something you have control over. Only when you’ve done all you can and have proven yourself as the absolute best and are still failing should you consider that it could be your gender. That should be a last resort. Even if it’s true, your credibility will rise with those who would not penalize you for your gender. Finally, do not date members of your unit or people who associate with them. Once you do, you cease being a colleague and sister-in-arms, and you become a possible target. There’s no coming back from that.

What was your favorite video game while deployed in Afghanistan?

That’s easy. We were addicted to Halo. It was amazing: We had a bunch of computers linked together, and we could play capture the flag with 16 or so people. You could hear people yelling out tactical info like “Help! Johnson is sniping us from the waterfall!” and such. So much fun.