Shooting Star

From Lockheed’s famed design chief Kelly Johnson, the first U.S. jet to fight.

:focal(500x316:501x317)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/42/59/4259ed22-1be6-40ef-8a19-3f7cce850da2/15i_on2014_si-94-13979_live-1.jpg)

On August 6, 1945, at 2:20 p.m., an aircraft taxied onto the runway at the Lockheed Air Terminal in Burbank, California, and began takeoff. The factory-fresh airplane took to the air after 2,700 feet of pavement.

When it was about 150 feet up and 500 feet beyond the runway, a large puff of white smoke billowed behind it. The aircraft continued the ascent for another half-mile, at which point the canopy came off. Five seconds later, the right wing dropped and the airplane nosed over.

The pilot, his parachute already unfurled, exited the right side of the aircraft. Although he cleared the cockpit, shroud lines from his chute caught in the tail assembly. The aircraft disintegrated in a small field at Oxnard Street and Satsuma Avenue in North Hollywood, producing a fireball that consumed everything within a 300-foot radius, including the pilot. The following day, the Los Angeles Times ran two front-page headlines: one informing the world of the U.S. atom bomb attack on Hiroshima, the other about the fiery death of Major Dick Bong.

During the war years, the loss of a U.S. Army Air Forces test pilot was not something that garnered much notice in the press. But Richard Ira “Dick” Bong was more than a test pilot; he was a war hero. Just eight months before, the 24-year-old had received the Medal of Honor for “aggressiveness and daring” in the skies over Borneo, and in Balikpapan and Leyte Gulf, the Philippines. He was America’s highest scoring ace in World War II, credited with shooting down at least 40 Japanese fighters and bombers. After so many victories, he was deemed too valuable to be risked in further combat and sent home. But after the inevitable public relations and war bond tour, Bong won an assignment as a test pilot, one of the most dangerous jobs in the Army.

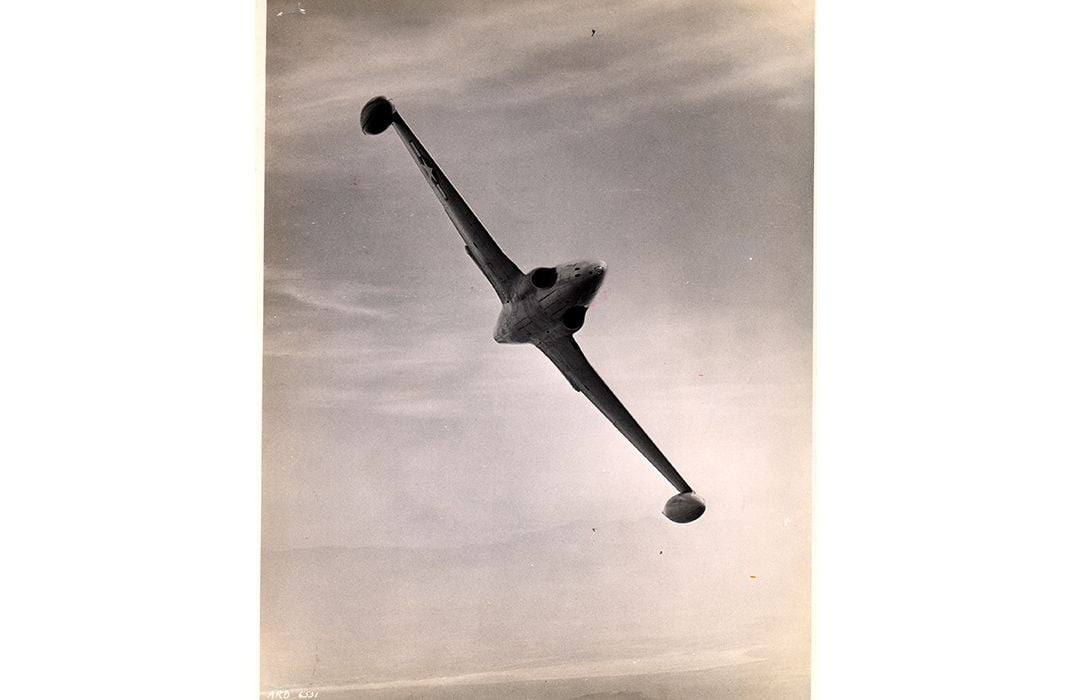

On the day he was killed, Bong had been flying the cutting edge in military aviation, the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star. It wasn’t the first U.S. jet to fly—that honor went to Bell Aircraft’s P-59 Airacomet, which first flew in October 1942, nearly three years earlier. But the P-59 was a dog with fleas, barely able to keep up with the piston-powered P-47s and P-38s of the time. The P-80—a highly maneuverable, winged torpedo that could exceed 500 mph in level flight, as well as a steady gun platform with a six-barrel .50-caliber stinger—belonged to a whole new generation.

Jet Offensive

After Bong’s death, the Shooting Star was grounded pending an investigation. Reporters quickly sniffed out that several other test pilots had died in P-80 accidents, one of them only four days before Bong. The press, the politicians, and the public all asked the same question: If the P-80 was too much for America’s premier fighter pilot, wasn’t it simply too dangerous to serve?

The last thing Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, commanding general of the Army Air Forces, wanted was a mob of taxpayers and politicians threatening to cut funding for his new jet. He had a vested interest in jets. In April 1941, he’d witnessed a test flight in England of the Whittle jet engine-propelled Gloster E.28. Working a deal to bring the Whittle engine to the United States (he promised the Brits an improved design for high-speed, high-temperature turbine blades in return for one engine and all British experimental jet data), Arnold designated General Electric to begin building them under license, and hired Bell Aircraft to build the first jet fighter.

But when the Airacomet fizzled and reports began streaming in of the impending arrival of a twin-engine Nazi superjet, Arnold turned to a company that the Army had turned down when it had pitched the idea of a jet fighter three years earlier.

On June 8, 1943, Clarence “Kelly” Johnson was at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, to sell Lockheed’s Model L-140. Johnson showed specifications and drawings, then threw down the gauntlet: He would deliver his jet prototype within 180 days. Johnson would later write in his memoir, Kelly: More Than My Share of it All, that General Frank Carroll told him,“You will have a Letter of Intent this afternoon by 1:30 p.m. There is a plane leaving Dayton for Burbank at two o’clock. Your time starts then.”

Lockheed had five days shy of half a year to build what Johnson was sure would revolutionize military aviation.

Under the Big Top

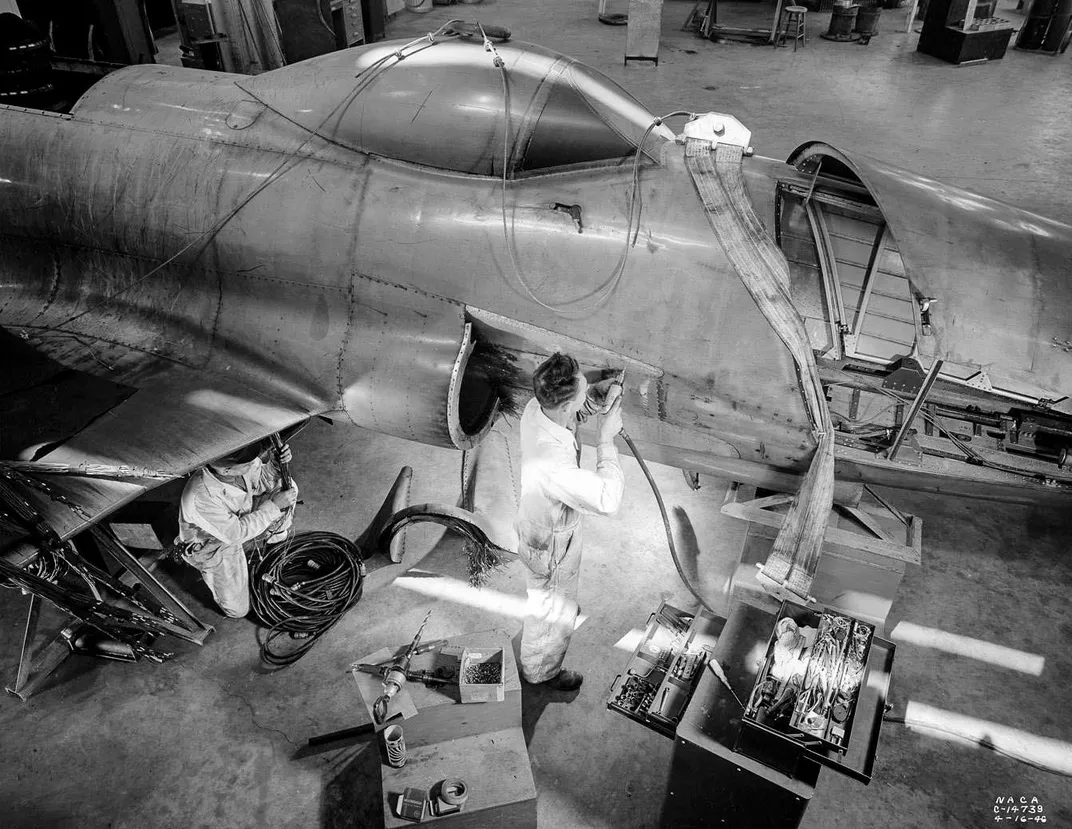

Johnson knew he’d need to sequester his top-secret project. But the aircraft factory’s six football fields’ of floor space was already spoken for, cranking out 28 warplanes a day. Returning to Burbank, Johnson did an end-run around company bureaucracy. He built his own manufacturing site around a small shack near the wind tunnel, and stole personnel from all over the plant. His team bought out a local machine shop to get the tooling it needed, built walls from a vast supply of wooden packing crates that came with the Wright Cyclone engines that powered their Hudson bombers, and topped off the ad hoc facility with a big top rented from a local circus. The unsightly hybrid was christened the Skunk Works after the still that made moonshine in the backwoods of Al Capp’s popular cartoon “Lil’ Abner.”

As summer turned to winter, America’s first real jet fighter took shape inside the most not-up-to-building-code facility in the San Fernando Valley. But the secrecy, drafty surroundings, and merciless schedule wore on the L-140 team: Flu season had arrived, and up to half the staff was out sick at any one time. Even the cops seemed to be against them: A jet engine expert on loan from Britain’s de Havilland Aircraft was stopped for jaywalking and jailed for not having a draft card. But on day 143 of the contract, a spinach-green XP-80 christened Lulu Belle was rolled out for its maiden flight.

On January 8, 1944, Lockheed test pilot Milo Burcham fired up Lulu Belle’s British Halford H-1 Goblin engine and took off. By the second flight of the day, Burcham was confident enough to alarm spectators by skimming low over the field at 475 mph and pulling up into a series of tight aileron rolls.

Only three weeks after that first flight, with most of Europe firmly under German control and the thought of jet-powered Me 262s picking off U.S. bomber crews never far from their minds, the Army brass asked Lockheed to incorporate GE’s yet-to-be-flown, but more powerful, I-40 jet engine into two new airframes, calling the resulting craft XP-80As. Arnold promptly amended the order to include 13 more, identifying them as YP-80As. A week later, Arnold authorized buying an additional 500 P-80As—all before a single one of the first GE-powered jets had taken to the sky.

But they did have Lulu Belle, and it was impressive. “I always dreamed of the perfect airplane and how I would fly it, but little did I realize I would ever see it,” wrote Lockheed test pilot Tony LeVier in his autobiography, Pilot. “As it reached flying speed, it went into the air with no more than a slight pull back on the stick. After the gear and flaps were up, it seemed almost like something you would dream about.”

Today, the Lulu Belle is on display at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

As Burcham, LeVier, and other Lockheed and Army test pilots put the XP-80 through its paces, Johnson and company were racing to build its more massive progeny. Designed to accommodate the bigger, 33 percent more powerful GE engine, the new designs were two feet longer, a foot taller, and two feet wider than Lulu Belle—and 25 percent heavier. Four days after Allied troops invaded Normandy, the first XP-80A, called Gray Ghost after the shiny lead-colored lacquer paint covering the airframe, first flew with LeVier at the controls.

So confident was Johnson of his new design that earlier that morning he asked LeVier to accept half his standard $5,000 fee for a first flight. After all, he’d flown Lulu Belle, and this was essentially the same jet, just a little bigger. But after the flight, when Johnson saw the sweat dripping down LeVier’s face and heard his report, he saw that LeVier was paid his full $5,000. The Gray Ghost prototype was hypersensitive in pitch, had thrust and flap issues, and had tried to cook LeVier like a goose, with cockpit temperatures soaring to 180 degrees Fahrenheit. But the Army hit the throttle on the P-80 test program, and eventually the most pressing issues, including baked pilots, were solved.

The same month, January 1945, a group of Me 262s brought down an entire squadron of 12 U.S. bombers. The Army again accelerated the P-80 program, putting it on equal footing with the Boeing B-29 bomber. In a war economy, where raw materials and skilled labor were tightly rationed, the Shooting Star was now at the front of the line. The military even contracted with North American Aviation to begin building them under license. It wanted 1,000 P-80s by the end of the year.

The rush came at a heavy cost. The first to fall was Lockheed chief test pilot Burcham, who died in October 1944 after losing an engine on takeoff. Then a Lockheed test pilot was killed in a mid-air collision during a night test. LeVier nearly bought it when a Gray Ghost’s engine disintegrated and tore off the prototype’s tail. Though he bailed out and survived, the P-80 program subsequently killed at least four more test pilots in addition to Bong, all in separate accidents.

Jack E. Sullivan, assistant operations officer at Muroc Army Air Field in California, recounted in Test Flying at Old Wright Field a harrowing P-80A test flight in 1946: “I set up and stabilized my run at 20,000 [feet] and everything looked great, but at about the midpoint of the throttle quadrant, things started changing fast,” he said. “The sound decreased, the tail pipe temperature dropped, the RPM, fuel pressure and everything were zeroing out. I had never experienced an airborne flameout before.”

Sullivan followed the air start procedures he’d practiced on the ground, but it was no use. “I tried again, and again and again, all the while losing altitude and stupidly keeping my head in the cockpit. I had not declared an emergency, still thinking I could get a restart. When it seemed certain that it wouldn’t happen, I yelled at the tower. They cleared me for landing.” Sullivan wasn’t able to reach either of the field’s two runways and instead landed on the grass near the base. But at least he survived.

Bong’s death—and all the prior fatalities that were now receiving the public attention they’d eluded before—brought the P-80 program to a halt. Arnold sent a teletype directing all P-80 commands to stand down, and for five new P-80As to be checked out from stem to stern and updated with any new part that would make them safer. He then ordered each flown for 50 hours. He ended the communiqué with a warning: “There will not be an accident. I repeat, there will not be an accident.”

The five handpicked P-80s and their pilots each dutifully flew 50 hours of some of the least-taxing tests in the history of Wright Field. Within weeks, Arnold was walking the halls of the Pentagon and Congress, propping up support for his program. He also launched a public relations offensive. Suddenly, the P-80 was everywhere: at state fairs, at airshows, on the covers of magazines, and at the 1946 Bendix Trophy Race.

Eager to demonstrate its new jet fighter, the Army Air Forces assigned four P-80s to fly from Van Nuys, California, to Cleveland, with several refueling stops along the way. One of them lost radio contact with the ground and got lost, while another experienced landing gear trouble; both had to drop out of the race. But of the two P-80s that reached Cleveland, one set a new speed record.

The end of World War II changed the Pentagon’s plans for purchasing warplanes. North American’s contract to produce the jet was canceled. The order for P-80s was cut from 5,000 to 2,000.

Fortune and Glory

By the second half of the 1940s, the P-80 was a staple at U.S. air bases. The A-model was supplanted by the B, the first operational U.S. jet with an ejection seat. Soon after, the C supplanted both. With each evolution, the Shooting Star became bigger, heavier, and more powerful.

“The ‘A’ felt good. It was easy to fly and very dependable, and the most fun of the bunch to fly,” says former Air Force fighter pilot Jack Broughton. “The B-model was sort of a doggy, in-between type that nobody thought too much about. The ‘C’ was a more powerful airplane. Far superior engine systems, a flameout aerostart switch, just a whole lot more sophistication.”

When the Air Force became an independent service in 1947, it eliminated the P (for “pursuit”) prefix in favor of F (“fighter”), redesignating its Shooting Stars F-80s. By 1949, the new Republic F-84 Thunderjets and swept-wing North American F-86 Sabres had supplanted the aging F-80s as the shiny new toys Air Force fighter pilots wanted to fly. Still, the majority of Air Force combat squadrons flew F-80s. When North Korea invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950, it was the Shooting Star that became America’s first jet to go to war.

Flying first from Japan, then from South Korean airstrips, F-80 crews helped establish aerial dominance over an inferior North Korean air force. But the situation on the ground was dire. The F-80 took on the role in Korea that the P-47 had in World War II: ground support.

“I got there while we were getting our butts kicked off the peninsula,” says Broughton. “It was colder than hell and we were hanging on by our teeth; everything else had been pushed back to Japan.” He flew his first mission from Taegu airfield in South Korea. “There were about a half-dozen disabled Russian T-34 tanks right off the end of the runway.”

With the Shooting Star’s speed, Broughton needed only 15 minutes to reach the frontlines, bringing bombs, rockets, napalm, and a full load of .50-caliber ammunition to support pinned-down troops at places that became known as the Sand Castle, the Punchbowl, and Heartbreak Ridge.

“By that time, the Chinese had come into the thing and it was like water over the dam, there were so many of them,” Broughton recalls. “We were usually a flight of four, and we’re looking at a hill of bad guys. We’re screaming at full power on the deck, pull the nose up, pick a nice spot, and each plane drops two napalm cans. That whole bloody ridge would be nothing but one big ball of fire. We go over the top, turn around, and use our six .50s on anything that might still be there.”

Tanks, troops, trains, bridges: Anything that could make war or help make war appeared in the illuminated gunsights of F-80 pilots. The Pusan Perimeter—a 140-mile defensive line on the southeastern tip of the Korean peninsula that included the port of Pusan—held, and eventually the frontline started moving northward. The Shooting Stars went with it.

“Once the Pusan Perimeter was busted and we started moving north, our missions became more interdiction,” says Broughton. “Sometimes we would have a fixed target quite a way up north, like a bridge or railway junction. The further north you went, the more likely you would be greeted by MiGs.”

In the early months of the war, the F-80 largely swept the skies of antiquated propeller-driven North Korean aircraft. But when Russian swept-wing MiG‑15s arrived, the 100-mph-slower F-80 lost the advantage. F-80 crews quickly learned to leave the MiGs to the more nimble Sabres whenever possible.

“On a flight up north, they shot down my number-two man on the first pass, and one of my flight had already aborted, so that left me and my number three,” says Broughton. “We had run into a group of 16 MiGs led by a Russian who was good.”

A dogfight among jets typically lasts only a minute or so. For 22 minutes, Broughton and his new wingman George Womack used the only edge the Shooting Stars had: the ability to turn inside the MiGs. “We’d just rack the -80s around, turning completely inside them, and they’d go scooting past,” says Broughton. “And when they did get into position to shoot at us, their guns were so poorly harmonized that when they pulled the trigger, there would be tracers all over the sky.”

Which is a lucky thing if you’re flying an outmatched airplane. Sweating so heavily he had to pull off his sunglasses to see, Broughton watched the MiG leader come in close behind and slide past him. “The MiG’s cannon fire goes all over the sky out in front of me and I just kept rolling to inverted and I’m looking right down in his cockpit. We were probably six feet from each other, canopy to canopy. I’m looking down in his cockpit and he’s so frustrated, waving around trying to hit something. As he started to scoot by, I just completed my roll and I’m right behind him as I let loose with my six machine guns up the MiG’s tailpipe. If I hit him I will never know, but the next thing he rolls over on his back and dives away and the rest of the MiGs go with him.”

The Shooting Star dropped its last bomb in combat on April 30, 1953. While its photo-reconnaissance version, the RF-80, continued to fly, the fighter was relegated to combat patrols over Japan. By the end of the war, in July 1953, 35 percent of the F-80Cs produced had been destroyed—14 by MiGs, 113 by ground fire, and 166 by accidents or unknown causes. A year later, the remaining Shooting Stars were phased out from active duty (the RF-80 stayed on until the end of 1957). The F-80 remained a staple in the Air Force Reserve and Air National Guards until 1958, and beginning in the 1950s, the United States sent surplus F-80s to six South American air forces.

Missile Impossible

As fighter technology moved on, the Air Force used its surplus F-80s for missile tests, and for ill-fated experiments in gasoline- and ramjet-power. It even tried towing one behind a bomber to extend its range; that didn’t work either.

Then the F-80 became the star of one of the most bizarre piloted test programs of the still-young nuclear age.

RASCAL (RAdar SCAnning Link) was Bell’s solution to a problem that vexed the Strategic Air Command: how to give bomber crews a fighting chance to survive the blast of a just-dropped, two-megaton W-27 thermonuclear device.

“It was one weird-looking aircraft,” says former Air Force test pilot Joe Kittinger, who in 1960 rose to fame for setting a world record for highest skydive (19 miles) from a balloon. “Bell Aircraft took old A-models and retrofitted them with these great big noses that extended five feet. That was for the [radar]. They put these hydraulically operated fins on their wings and replaced the fuel in the tip tanks with the avionics package of the RASCAL missile.” At $2.2 million each, real RASCALs were too pricey to throw away on training, so Bell built the Air Force the best surrogate it could, using repurposed P-80As.

Along with the nuke, the 18,000 pounds of air-to-surface missile packed 3,000 gallons of JP4 and white fuming nitric acid oxidizer in a 31-foot-long, four-foot-wide package. Carrying only 40 minutes of fuel, the RASCAL imitator was limited to two simulated bomb runs per flight. After lauching the weapon, the bomber pilots would turn tail to escape the blast, while the bombardier/navigator would use a joystick to guide the missile to the target remotely.

“We got right underneath the bomb bay of the airplane and they gave you a countdown, 5-4-3-2-1,” Kittinger says. “When they said ‘Launch’ we would push the power full forward and press the command button, giving the bombardier radio control of the plane. They would climb us up to 45,000 feet, fly us out, and then give us a dive command.”

Non-pilots remotely flying nuclear-tipped missiles with 1950s radio technology was exactly as difficult as it sounds.

“It was a pretty violent ride,” Kittinger recalls. “We had a disconnect button on the top of the stick to quickly take back control if something went way wrong. But they’re flying the plane remotely and you don’t want to disturb things by touching the stick. So the whole time we’re getting jerked around the cockpit, and our hands are on both sides of the stick but not touching it. As the flight continued, the stick is going this way and that—and we’re chasing it around the cockpit with our hands.”

The bombardiers would even steer the F-80 during the near-vertical plunge to target. “We got down to minimum altitude, usually 1,000 feet, then we’d hit the button and do the pullout,” says Kittinger. “They got so good that we would call the guys up and say, ‘Okay, pull us out of the dive.’ ”

For six months in 1957, Kittinger got 20 occasions to chase his F-80’s remote-controlled stick before the RASCAL program was canceled.

It was an odd coda to the F-80’s tour of duty in Korea, a conflict of the nuclear age but fought with conventional weapons: By the time the Korean War ended in 1953, F-80s had flown 98,515 sorties, firing 81,000 rockets and dropping 41,493 tons of bombs and napalm. They had downed 37 enemy aircraft and destroyed 21 on the ground.

This from an airplane built in a circus tent.