Slim and Bud

Meet Charles Lindbergh the barnstormer—as he interviews his oldest flying buddy.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/08B_ON09-flash.jpg)

Charles Lindbergh's account of his record-setting transatlantic flight, We, was rushed to press in 1927. He later admitted that "being young, and easily embarrassed" and wanting to present only the most positive image of aviation, he left out what he called "much of greatest interest." Acutely aware of his place in history, Lindbergh wrote again, in greater detail, of his famous solo flight, publishing The Spirit of St. Louis in 1953. It won a 1954 Pulitzer Prize.

Lindbergh's belief that the history of aviation should be told reached beyond his own part in it. He often encouraged pioneering aviators, including Orville Wright, to write their memoirs. For years Wright dodged the opportunity to tell his story, even while objecting to the errors introduced when others told it for him. "It is a tragedy," Lindbergh wrote in his diary in 1939, "for Wright is getting well on in years, and no one else is able to tell the story as he can."

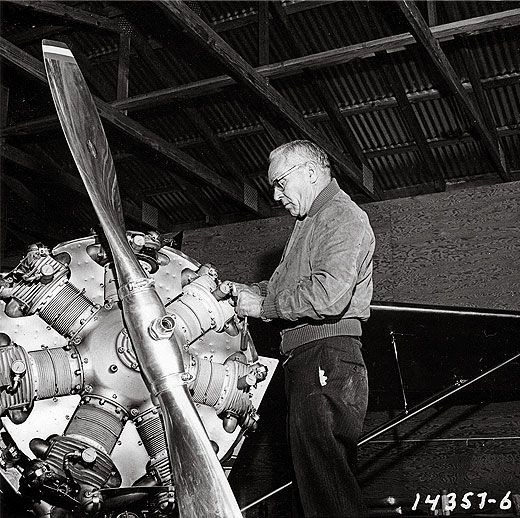

Another pilot whose story Lindbergh thought deserved to be told was his closest friend, Harlan A. "Bud" Gurney. Since his first airplane ride, in 1922, Gurney had been beside Lindbergh, later becoming, like Lindbergh, an airmail pilot, and afterward a captain with United Airlines and a restorer of vintage aircraft. It was Gurney whom Lindbergh trusted as technical advisor on the 1957 film The Spirit of St. Louis, starring Jimmy Stewart.

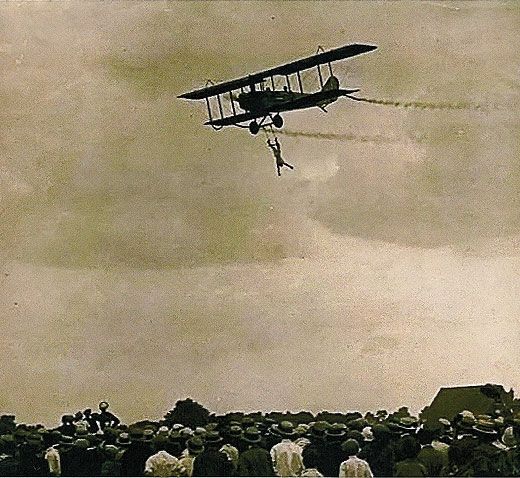

During barnstorming trips in the early 1920s, Gurney, then 18, and Lindbergh, 21, shared stories around the campfire, and had lazy afternoon conversations under the wing of Lindbergh's Curtiss JN-4 Jenny. Certainly, no one knew Lindbergh better as a young adult than Gurney, and vice versa.

Both Lindbergh and Gurney were independent children, and, as teenagers, accepted adult responsibilities. They were both handsome, yet shy with girls; mechanically gifted, and adventuresome.

In 1969, Lindbergh, then 67, and Gurney, 64, met in the Gurneys' California home. While Gurney's wife, Hilda, puttered in the kitchen and the tape recorder spun, Lindbergh interviewed Gurney. It may be the only time Lindbergh was on the opposite end of a microphone.

Give a brief outline, if you could, [of] where you were born and how you started out at Lincoln. How you got to the sand hills of Nebraska. — Charles Lindbergh

The one-and-a-half-hour interview has been heard only by those close to the Gurney family, and visitors to their hangar. In the interview, Gurney refers to the man beside him alternately as "Charles Lindbergh," or "Slim," a nickname for which Gurney often took credit. When they first met, Lindbergh called his friend "Buddy," which he later shortened to "Bud"; it stuck for the rest of Gurney's life.

The first 40 minutes of the interview are devoted to Gurney's childhood. He struck out on his own at age 13, when he learned his family didn't have enough money to buy his schoolbooks.

The rest of the interview supports what is known of Lindbergh's arrival at the Lincoln Aircraft Corporation to sign up for flying lessons in 1922; Lindbergh's and Gurney's first flight, side by side in Otto Timm's Lincoln-Standard J-1; and other adventures to which Gurney adds his own impressions.

In contrast to Lindbergh, Gurney never downplayed the danger of early flying. Gurney often feared for his life, even then thinking that some stunts were "an idiot thing to do." At least two barnstorming adventures are mentioned in the interview that do not appear in books written by or about Lindbergh.

To say Lindbergh and Gurney were both reckless and brave would be an understatement. Although they were to perform in aerial circuses as wingwalkers and make double and triple parachute drops, Gurney's first jump was prompted by a dare from Lindbergh.

Circling over the fields of Lincoln, Nebraska, Gurney jumped from an airplane piloted by his employer, Ray Page, and dropped into the garden of Mrs. O'Sullivan. As he descended, he heard her shout warnings not to land in her bean patch. He also saw a cloud of dust headed his way, created by Lindbergh on his Excelsior motorcycle, racing in such haste to pick him up that he fell off. Elated with their success, the boys celebrated with ice cream.

Lindbergh and Gurney sometimes disagreed on details. When Gurney reminded Lindbergh about getting a lot of press by performing "dangerous stunts" with Page's Aerial Circus and almost being arrested for recklessness, Lindbergh claimed that he did not remember, adding that the act wasn't that spectacular; "not much happened."

Some weeks I barely made expenses, and on others I carried passengers all week long at five dollars each. — Charles Lindbergh, We

Offering to share income, Lindbergh invited Gurney to go barnstorming in his Jenny during the warm months of 1923. Gurney recalled hoping it would be an "adventure." It was.

"We left to barnstorm in Ashland, Nebraska," Gurney said. "[Lindbergh] left a carborundum can on the magneto distributor, or by it—and it lay between the cylinders." Lindbergh's face must have shown surprise, because Gurney laughed.

"And [it] shorted out the magneto. We had a forced landing. He landed in an open field. We got on top of the engine to see what was wrong with it, and lifted out this carborundum can, and of course the engine ran perfectly after that. He's forgotten about that! Do you remember now?"

Lindbergh was succinct: "No, I don't remember it." "You don't?" asked Gurney. "Oh, you should remember that. I sure do."

The rest of their "adventure" included a desperate attempt to keep the Jenny from blowing across a pasture during a sudden thunderstorm.

Gurney's account of being knocked unconscious for several minutes by lightning is prefaced with a disclaimer:

"I don't know if I'm going to have much agreement with Charles Lindbergh on this, but this is the way I remember it.

"I was holding on to the stabilizer wires underneath the tail of the airplane.... The thing I remember next—which seems strange to me that [Lindbergh] doesn't—[is] that I was lying in about three inches of water...and Charles Lindbergh...said to me, ‘Did you feel that little shock?' "

Neither backed off his version, but eventually Lindbergh conceded that Gurney "may have gotten a worse shock," to which Gurney gracefully concluded, "I don't know.... At any rate, it wasn't a very successful barnstorming trip."

There were several forced landings in Lindbergh's Jenny, and it is amazing that the only serious injury was to Gurney while he was performing a parachute jump after the International Air Races in St. Louis in October 1923.

Lindbergh and Gurney traveled separately to the races, where they stood among 140,000 spectators and watched biplanes roar around pylons at 200 mph. Both found the spectacle exhilarating, but, said Gurney, "it couldn't all be fun. There was work to be done." Gurney was promised $50 for a parachute drop over the grandstand, money that would allow him to return to school. Lindbergh agreed to carry Gurney aloft in his Jenny. When Gurney jumped from the Jenny, he dropped into the slip stream of another aircraft, and his parachute collapsed. While spectators watched, Gurney fell to the ground.

"I hit it...more or less horizontally, and...broke [a] bone in one arm and did some damage to the socket. [I] put the parachute over my shoulder...and I walked across the field, and I almost made the hospital tent one quarter mile away. Almost. When I woke up I was in an ambulance, and Charles Lindbergh was beside me."

For three weeks, Gurney had one daily visitor—his friend Slim. When Gurney felt strong enough to leave the hospital, he had no way to settle his bill. "They weren't going to let me out," said Gurney. "After all, I wasn't a charity case. I'd won quite a bit of money at the St. Louis Air Races although I hadn't collected it. And they had no way of collecting the money, so I had to collect it. And guess who I collected it from? Charles Lindbergh!

"[P]rior to entering Barnes Hospital in St. Louis, I'd met a boy named Francis Stimson.... I introduced him to Charles Lindbergh. While I was in the hospital, Charles Lindbergh sold his Jenny to Francis Stimson and was teaching him to fly."

Because Gurney's accident and the sale of Lindbergh's Jenny happened so close together, some historians have speculated that Lindbergh sold his Jenny to pay Gurney's hospital bill. However, aviation historian Chet Peek, who has reviewed the unedited manuscript of The Spirit of St. Louis, says that Lindbergh was paid for his Jenny on November 14, 1923, long after Gurney had left the hospital. It's possible that the money Gurney collected from Lindbergh was Gurney's own prize money, which Lindbergh retrieved for him.

No need to worry about [Gurney] — clear head — steady nerves — agile as a monkey. — Charles Lindbergh, The Spirit of St. Louis

Gurney spent that fall picking up odd jobs around the St. Louis airfield, and doing aircraft repair work Lindbergh referred to him. Lindbergh's mother, Evangeline, visited at Christmas; Gurney recalled, "Mrs. Lindbergh...had never seen a wing-walking show, and Slim and I made up our minds we'd show it to her."

Gurney confessed that he was "very much taken" with Mrs. Lindbergh. "I thought she was about the most perfect woman in the world. And she was."

With Gurney still wearing a steel brace on his arm, Lindbergh took him aloft. Using one arm to balance on the wing of the "decrepit" Jenny, Gurney managed to get through several stunts before his threadbare pants were blown apart at the seams.

"[T]hinking as much as I did of Charles Lindbergh's mother, having this disgraceful show...having no pants on—they just hung onto the belt and flew in the slip stream. Nothing on but a thin pair of shorts!

"I tried to get back in the cockpit, and you know, for some reason that Jenny went out of control. It went up and down and crossways and every time I tried to dive for the cockpit there were forces generated that kept me from getting into that cockpit! And I've always suspected that Charles Lindbergh had a hand in those crazy maneuvers."

Gurney concluded, "Well, as much as I already thought of Evangeline Lindbergh, I thought what a wonderful sense of humor she had. I think no comedians could have put on a show like ours."

Lindbergh's biographical accounts of his reckless "adventures" are sometimes minimalistic, almost to the point of denial. There were probably few people in the world who would challenge Charles Lindbergh. But in this taped account, it is obvious that Gurney has no such inhibitions. With diplomacy based upon mutual respect and friendship, Gurney holds firm even when Lindbergh disagrees.

It is tantalizing to imagine further interviews in which Gurney describes his years with Lindbergh as an airmail pilot for Robertson Aircraft Company in St. Louis during the mid-1920s, or their lives together and apart after Lindbergh became the most famous man in the world.

It is a loss to history that, like so many pioneer aviators of the Golden Age, Gurney did not write his autobiography. Yet, thanks to Charles Lindbergh, we have at least one chapter.

Giacinta Bradley Koontz is an aviation historian.