Slurp or Gulp?

“Well the rain exploded with a mighty crash, as we fell into the sun…” As a kid, when I heard Paul McCartney sing those words, I sort of envisioned this:Now astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope have envisioned something like this happening to a planet orbiting a star 600 light-years away….

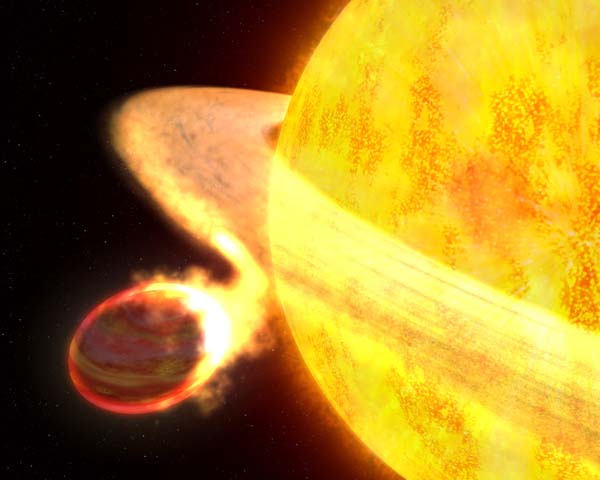

"Well the rain exploded with a mighty crash, as we fell into the sun..." As a kid, when I heard Paul McCartney sing those words, I sort of envisioned this:

Now astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope have envisioned something like this happening to a planet orbiting a star 600 light-years away. But there's no rain to be found on this eerie world.

The planet, WASP-12b, about 1.4 times the size of Jupiter, is steadily losing mass to its host star, which, like our sun, is a yellow dwarf. Discovered in 2008 by a team led by Carole Haswell of the Open University of Great Britain, WASP-12b orbits just one stellar radius from the blistering surface of the host—much closer than tiny Mercury, the innermost planet in our solar system, orbits the sun. Mercury completes an orbit every 88 Earth days. WASP-12b circles its star in 26 hours. "If you were on the outskirts of the planet," says Haswell, "the star would pretty much fill your view of the sky."

She says "outskirts," because the planet is basically a roiling, football-shaped (due to tidal forces) ball of gas heated to 2,800 degrees Fahrenheit—the hottest world yet discovered. Each time WASP-12b passes in front of the star, which dims the star's light a bit, Hubble's Cosmic Origins Spectrograph detects heightened levels of aluminum, tin, manganese, and other elements, which means they exist in the planet's atmosphere. Within 10 million years, possibly, the planet will basically evaporate. Or it may go gulp, right into the fire, before then.

What will that look like? Well, says Haswell, "My conscience is clear if I give you the caveats." First off, it may not really be what we think of as a planet; just an opaque mass that passes in front of the star once a day, surrounded by a tenuous gas cloud of almost three Jupiter radii. That cloud is so expanded from the star's heat that it is being gradually slurped away by the star. "The opaque planet is bigger than models of gas giant planets predict," she says. "If there is a hard metal core, this tends to make the radius of the planet smaller."

Theoretical work published last winter by Shu-lin Li of Peking University predicted that the planet's tidal distortion makes the interior so hot that it greatly expands the outer atmosphere, which has now been confirmed by Hubble. "Since we suspect, after the work of Li that this planet is inflated by tidal heating," says Haswell, "there could be a hard metal core." At some point, that metal core would begin to boil. "But this depends on whether the evolution causes the separation between the star and planet to increase or decrease. It's fair to say we don't have a complete picture of it yet." The angular momentum would determine whether the planet eventually falls inward or drifts outward. But if it stays where it is, it will continue losing "atmosphere" to the star.

The planet could at some point get gulped into the star like an oyster, or smeared onto the stellar surface. If Earth-bound astronomers are around in 10 million years to watch this happen, what might they see? With current technology, says Haswell, astronomers would note no further dip in the light from the star, or the "Doppler wobble" caused by the planet's mass tugging on the star, as it transits each day.

But 10 million years is a pretty long time—maybe by then we'll watch it through some future telescope in high-resolution, or be out there in a starship for the occasion.

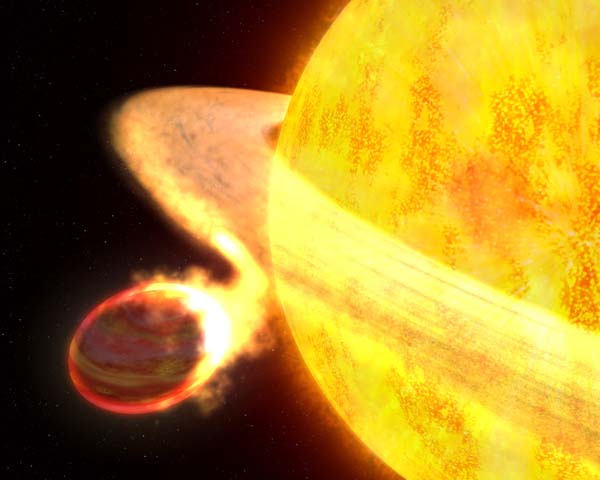

Now astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope have envisioned something like this happening to a planet orbiting a star 600 light-years away. But there's no rain to be found on this eerie world.

The planet, WASP-12b, about 1.4 times the size of Jupiter, is steadily losing mass to its host star, which, like our sun, is a yellow dwarf. Discovered in 2008 by a team led by Carole Haswell of the Open University of Great Britain, WASP-12b orbits just one stellar radius from the blistering surface of the host—much closer than tiny Mercury, the innermost planet in our solar system, orbits the sun. Mercury completes an orbit every 88 Earth days. WASP-12b circles its star in 26 hours. "If you were on the outskirts of the planet," says Haswell, "the star would pretty much fill your view of the sky."

She says "outskirts," because the planet is basically a roiling, football-shaped (due to tidal forces) ball of gas heated to 2,800 degrees Fahrenheit—the hottest world yet discovered. Each time WASP-12b passes in front of the star, which dims the star's light a bit, Hubble's Cosmic Origins Spectrograph detects heightened levels of aluminum, tin, manganese, and other elements, which means they exist in the planet's atmosphere. Within 10 million years, possibly, the planet will basically evaporate. Or it may go gulp, right into the fire, before then.

What will that look like? Well, says Haswell, "My conscience is clear if I give you the caveats." First off, it may not really be what we think of as a planet; just an opaque mass that passes in front of the star once a day, surrounded by a tenuous gas cloud of almost three Jupiter radii. That cloud is so expanded from the star's heat that it is being gradually slurped away by the star. "The opaque planet is bigger than models of gas giant planets predict," she says. "If there is a hard metal core, this tends to make the radius of the planet smaller."

Theoretical work published last winter by Shu-lin Li of Peking University predicted that the planet's tidal distortion makes the interior so hot that it greatly expands the outer atmosphere, which has now been confirmed by Hubble. "Since we suspect, after the work of Li that this planet is inflated by tidal heating," says Haswell, "there could be a hard metal core." At some point, that metal core would begin to boil. "But this depends on whether the evolution causes the separation between the star and planet to increase or decrease. It's fair to say we don't have a complete picture of it yet." The angular momentum would determine whether the planet eventually falls inward or drifts outward. But if it stays where it is, it will continue losing "atmosphere" to the star.

The planet could at some point get gulped into the star like an oyster, or smeared onto the stellar surface. If Earth-bound astronomers are around in 10 million years to watch this happen, what might they see? With current technology, says Haswell, astronomers would note no further dip in the light from the star, or the "Doppler wobble" caused by the planet's mass tugging on the star, as it transits each day.

But 10 million years is a pretty long time—maybe by then we'll watch it through some future telescope in high-resolution, or be out there in a starship for the occasion.