The Soviet City in the Sky

In 1928, a Russian architect proposed taking urban living to new heights.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/14/d8/14d84027-a5d1-43ab-a53a-2ffee6c1c6ab/cabin.jpg)

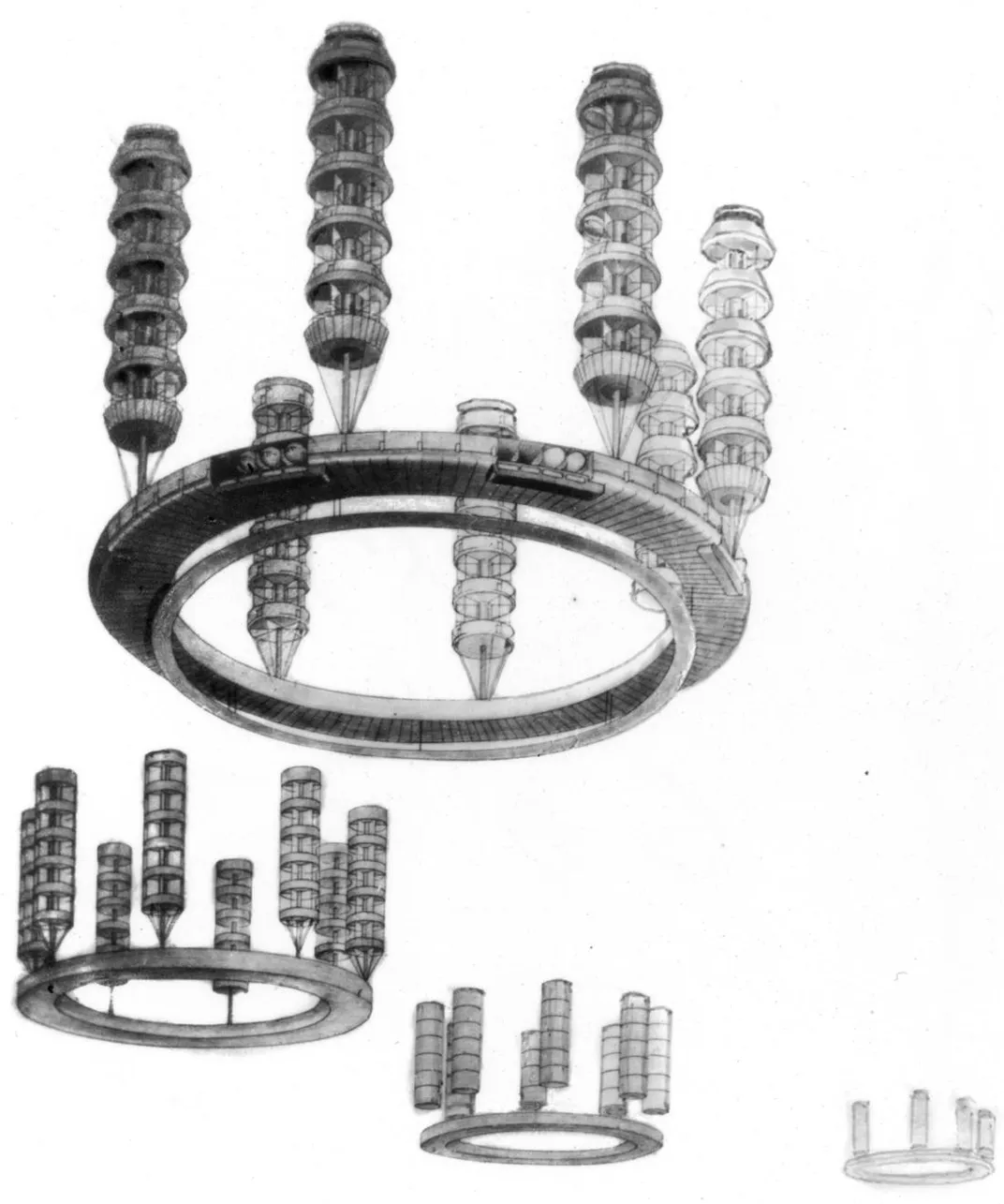

There’s always one student who can’t meet the deadline, and in 1928 at the Vkhutemas Technical Institute, it was Georgii Krutikov. While the rest of the architecture students and faculty packed for summer break, Krutikov feverishly continued sketching his designs. When he finished, he argued in his oral presentation that since the landmass available to humanity was limited, and the population was exploding, a radical solution was needed. His idea? Mobile architecture. By “mobile,” he meant to place buildings in the sky, so the land could then be cultivated.

After Krutikov’s presentation, witnesses recall “a terrible quiet reigned.” Finally, someone asked Krutikov how long he’d spent on the idea. “Fifteen years,” the student replied calmly.

There were no further questions.

When the press learned that Krutikov had been awarded the title “architect-artist,” he was mocked as the “Soviet Jules Verne,” and the diploma committee castigated for training “day-dreamers,” not “builders.” The committee replied that while Krutikov’s project was “visionary” and “utopian,” the other students’ designs (62 in all) were all “highly practical.”

The avant-garde artist is the subject of a newly translated work, Georgii Krutikov: The Flying City and Beyond, by Selim Omarovich Khan-Magomedov (2015, Tenov Books/University of Chicago Press). Krutikov, as it turns out, was intensely interested in aviation—particularly airships—and drew designs for gondolas and airplane factories. He also subscribed to aeronautical magazines, and corresponded with prominent scientists such as Konstantin Tsiolkovsky.

Krutikov proposed that the city would be suspended in the air by some kind of atomic energy—he’s a little iffy on the details—and people would travel from the surfae to the airborne residential pods in a “cabin,” a kind of space capsule that was capable of traveling through air, on the ground, and underwater. The cabin would be equipped with self-cleaning walls (why?) and furniture for one person, which would be able to change shape depending on whether the traveler was sitting or standing.

What became of the Flying City? Although Krutikov’s design wasn’t published at the time, architects recalled his visionary work—and the furor it caused—many years later, during the Space Race of the 1950s, according to Khan-Magomedov. Krutikov himself died in 1958, after a career designing residental buildings, Metro stations, and conserving architectural landmarks. While researching his book, Khan-Magomedov tracked down Krutikov’s classmates, many of whom could draw portions of the Flying City from memory. They believed that nothing remained of the work, neither sketches nor photographs. But Khan-Magomedov located a family member and uncovered a treasure trove: the original Flying City drawings, photographs of students’ work, unpublished manuscripts, and more. With these documents, the details of Krutikov’s vision finally come to light.

Images from Georgii Krutikov: The Flying City and Beyond used with the permission of the publisher.