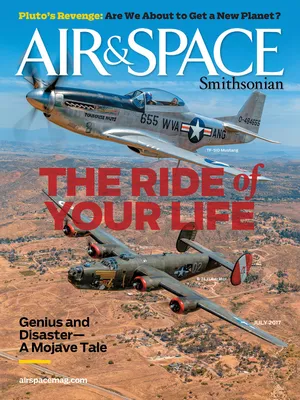

Amazing Stories of the Space Age

Some of the space history stories you’ve never heard are the most interesting.

:focal(816x307:817x308)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/43/35/433593e3-f36d-4cd1-bccb-b9eb07547435/disney_vb.jpg)

In science writer Rod Pyle’s new book, Amazing Stories of the Space Age, he has assembled an engrossing collection of stories that show the sometimes misguided ambitions of scientists and engineers who nonetheless contributed to the advancement of aerospace. He spoke with senior associate editor Diane Tedeschi in April.

Air & Space: Why did you decide to write this book?

Pyle: I have made TV documentaries and written books about spaceflight. Along the way, I would find these odd little stories of programs planned but not flown and less-known details about missions that were flown. I started collecting them. When I had enough tidbits, I began working on Amazing Stories of the Space Age.

What is the most shocking or preposterous story you came across?

Probably Project Orion, the atomic rocket. This had been declassified for decades, but the notion of powering a spacecraft with atomic bombs repeatedly exploding behind it was just incredible.

I noticed that many of the stories you write about occurred during the Cold War between the U.S. and the former Soviet Union. How much does fear and anxiety drive the development of technology?

Quite a lot I think. It’s important to bear in mind that the Space Age was a kind of perfect storm of conditions: We had just come out of World War II as a victor, with incredible technological achievements at hand, both our own and those inherited from the Germans. We had a convenient arch-enemy in the Soviet Union, and a president who needed a “win”—the Soviets were handing us our lunch in rocket power and spaceflight firsts, and Kennedy had just experienced the disgrace of the Bay of Pigs debacle. He wanted some kind of non-shooting competition to prove that America had superior technological capability, a better system of governance, better educational institutions—just more mojo all around. When queried, his advisors famously told him that the Soviets could probably beat us with a space station, and possibly even to lunar orbit, but landing humans there and bringing them back might give us a chance at being first. Thus, the race to the moon was born.

I recently spoke with Lori Garver, former deputy administrator for NASA, and she said that the key motivators for big human achievements like spaceflight are a combination of fear, greed, and glory. This includes the basic survival instinct—let’s get the solar system populated in case something happens on Earth—and the greed that’s intrinsic in the rise of the private sector in spaceflight. Glory is self-explanatory. So here’s hoping that these eternal motivators can be used in a more constructive and lasting fashion—namely, the true opening of the solar system instead of another one-shot expeditionary dash like Apollo, glorious though it was.

Do you think the U.S. will enter a Cold War-like competition with China? Are we already in one?

There are those who pine for another such competition, citing China as our new competitor, or to some even an enemy. But we are so intertwined with China economically and geopolitically, I see this as unlikely. The Chinese may serve as a short lever in a sense, able to cause some motion in our programs. I would love to be on the floor of the [U.S.] Senate when the Chinese land humans on the moon in a few years and one senator turns to another and says “How could you let this happen?” All of the United States “let this happen.” We took our eyes off the space prize. However, in the end I see the rise of the private sector in space being a better motivator for more advanced spaceflight capabilities. There appear to be solid economic arguments for the development of Earth orbit and cislunar space. The benefits range from global cheap broadband—imagine the new and clever minds that will contribute new and innovative ideas to the marketplace—to abundant, clean, and ultimately cheap solar power. These are just two examples of space technologies that will span the chasm of time and investment, and provide unimaginable benefits to us all.

While researching the book, did you ever think about what Nazi Germany could have accomplished had it channeled its technology for beneficial causes instead of weaponry?

Honestly, I was so caught up in the audacious nature of projects like the Silverbird Amerika bomber and the lineage of the Apollo program’s Saturn V, that I thought of pre-war Germany as more of an amoral technology forge, and of wartime German technology as a desperate, ultimately not very effective R&D program. But you have a point: had these energies been channeled toward arguably pro-human endeavors like the Apollo program or the International Space Station, they could possibly have made great strides, had [Germany’s] interwar economy been strong enough.

Do you think we should return to the moon?

This is the big question that spurs debate—like tossing gasoline onto a flame when space people get together. My personal opinion is that if Elon Musk can really develop a business case for Mars—I spoke to Gwynne Shotwell, president and COO of SpaceX last week, and she thinks he can—then the push to Mars might make sense. But if we are talking about efforts like the emerging NASA-private-international partnerships we are seeing, the moon makes more sense to me. It’s close, it’s achievable, and it has resources, though probably not as rich as those found on Mars. There is a lot we can do near to and on the moon: not just bases and science, but space infrastructure development and technological R&D, which can help to create a long-term human presence in the solar system. Accomplishing the same thing on Mars would be much more challenging. I just hope we don’t get stuck at the moon for 35 years.

We can do whatever we decide to do. I’d like to paraphrase a wonderful quote that Gene Kranz [NASA Flight Director during the Gemini and Apollo programs] gave me when I interviewed him a few years ago. We had just finished discussing the Apollo program, and he paused for a moment. Then he looked at me very seriously, with that steely-eyed missile-man gaze of his, and said, “What America will dare, America can do.” It gave me chills. My reaction is, we know what we can do when properly motivated—so what do we dare? That really is the question before us as a nation—and a world—of scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs, and citizens.