Spaceport at the Top of the World

How an ore-mining town in Sweden sees a new identity over the horizon.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Spaceport_2_FLASH.jpg)

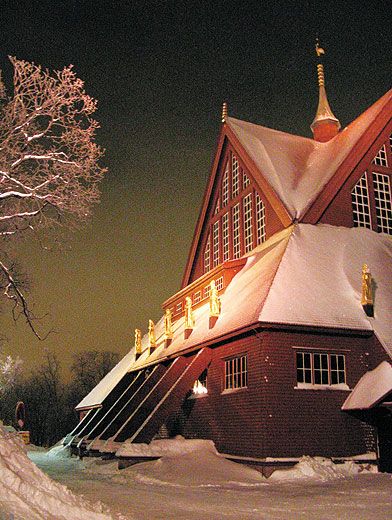

On paper, the Swedish town of Kiruna seems an unlikely place to build Europe’s first commercial spaceport. Located 90 miles above the Arctic Circle and nearly 600 miles north of Stockholm, Kiruna boasts a staggering set of disadvantages: an iron mine relentlessly expanding, eating away at the ground beneath the town, a vast expanse of forests, no sunlight for weeks at a time, and temperatures that for four months of the year barely rise above 15 degrees Fahrenheit.

Yet in 2007, the Swedish government announced an “agreement of understanding” with Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic to make Kiruna the company’s first launch site outside the United States. If all goes according to schedule, Virgin could be flying space tourists to the edge of Earth’s atmosphere from New Mexico as early as next year. With plans for several flights each week by 2013, Kiruna could soon be hosting hundreds of space tourists. Suborbital spaceflights from Kiruna, Virgin Galactic spokespeople have promised, could send tourists straight through the Aurora Borealis.

Though it will be new to many tourists, Spaceport Sweden is not undiscovered. Because of its remote location and minimal air traffic, Kiruna has been home to an array of aerospace activities for almost half a century. The Swedish government established a space research center here in 1964. The center, called Esrange, today includes a 3,240-square-mile range for launching sounding rockets.

But it’s the prospect of people flying into space from their snow-covered airfield that has the residents of Kiruna excited. And hundreds of people have put down $20,000 deposits to be among the first tourists to fly with Virgin Galactic into space. The experience is targeted at a very narrow market, namely people with $200,000 to spend on a vacation. With typical Virgin flair, the Kiruna flight is being packaged as an Arctic adventure complete with a stay in a hotel made of ice and snow, sleigh and snowmobile rides through the wilderness nearby, and, of course, spaceflight.

I went to Kiruna to find out how the company leading the space tourism race became interested in the town despite its handicaps. Kiruna has few natural resources beyond a rich vein of iron ore stretching more than a mile below the ground. It’s not a skiing destination, and there are few cultural attractions. There’s an ample supply of reindeer, but otherwise little charismatic wildlife.

Yet the town has been gifted with something less tangible: a willingness to bet on seemingly crazy ideas—and brilliant marketing. “We have the space facilities with Esrange, and a lot of experience having tourism in Kiruna,” Mayor Kenneth Stålnacke says. “It’s a good idea to marry these together: space and tourism.”

Kiruna’s economy is dominated by the mine, which is on the edge of town. In the past five years, the mine has made the town famous, thanks to a serious problem with an audacious solution. Since the seam of iron ore cuts diagonally below the town, the excavation has slowly been consuming the ground underneath Kiruna’s houses and streets, causing subsidence. Over the next 50 years, the whole town will be relocated to a safer location. A few houses, century-old wood structures built for the first mine workers, have already been shifted. The danger zone is now just a few hundred yards from the town hall, which will be abandoned by 2013.

Kjell Törmä, editor of KirunaTidningen, a local magazine, has spent the last few years documenting the move. One afternoon, not long after dark (which is to say, slightly before 4 p.m.), he picked me up at the doomed town hall in a red Mitsubishi and drove me through neighborhoods destined to collapse within a decade. The century-old mine, he says, is the town’s reason for being, though of its 24,000 residents, the company employs only 1,800 people, of whom 400 work in the mine itself.

Like everyone in town, Törmä is enthusiastic about the potential of space tourism to bring jobs to Kiruna. “Most people know we can’t just live on the mine,” he says. Its heyday was in the 1970s, and since then, the town has shrunk by 7,000. As operations at the mine have gotten more automated, the number of people working there has dropped by half. “In the ’70s, the thinking changed a little bit,” says Törmä. “People realized we need to have other businesses.”

The town began investing in tourism, trying to attract visitors during Kiruna’s short summer. White-water rafting, fly-fishing, survival training, and canoeing were all popular. Some people came just to experience the 24 hours of sunlight at summer’s peak. But for more than half the year, the town’s hotels were empty.

In 1989, a Kiruna entrepreneur named Yngve Bergqvist changed that completely. Bergqvist organized an ice festival in Jukkasjärvi (seven miles from Kiruna), inviting artists from Japan to carve ice sculptures and construct an exhibition building made of ice and snow. The festival caught on, and a few years later, Bergqvist lodged a group of corporate clients in the empty ice house overnight.

They survived, and a business was born—the IceHotel, which has grown from its humble origins into a global brand. Each winter, a hotel with dozens of rooms is built out of a mixture of snow and ice (“snice,” IceHotel employees call it). Guests pay between $200 and $600 to spend a night bundled in thermal sleeping bags on reindeer skins in a 23-degree room.

The IceHotel’s fame transformed Kiruna into a winter tourist attraction. The town’s high season is now mid-December through the end of March. Underemployed truck drivers plow racetracks on frozen lakes for car companies and tourists who want to try ice driving; there are snowmobile and sled-dog tours for adventurers, and reindeer-spotting trips for nature lovers.

In many places, someone wanting to build a hotel out of ice—and charge people $600 a night to sleep in it—might have been laughed out of town. But here people seem to take the unusual in stride. Perhaps that’s one reason the town is so supportive of Virgin Galactic’s equally outrageous plans. “Bergqvist showed it was possible to make crazy success out of what’s just outside the house,” Törmä says. “Many people are very proud of these crazy ideas.”

Spaceflight could mean yet another tourist boom in Kiruna. Johanna Bergström-Roos, information manager at Esrange space center, says the minimum stay for space tourists would be three days—two for orientation and classes to make sure people know how to handle themselves in flight, and one for the flight itself.

And those rich enough to buy $200,000 trips to space are going to want to share their experience with spouses, kids, maybe parents and friends. “If a space tourist comes, they’ll bring five, 10, 15 people along,” Bergström-Roos says. All those people will need places to stay and things to do. Plans are already in the works: Bergström-Roos showed me sketches for Space City 2020, a development program that would capitalize on the spaceport’s success with space summer camps, centrifuges to simulate high G-forces, and video links to let people on the ground share the spaceflight experience in real time.

Dan Bjork, the IceHotel’s marketing director, says the hotel is working with Spaceport Sweden (a consortium made up of four corporations in Kiruna, including the Swedish Space Corporation, and the IceHotel) to come up with a plan to pamper Virgin’s customers, from accommodations and entertainment to working with Virgin’s medical staff to produce just the right pre-flight menu for their four-star restaurant.

Bergström-Roos estimates that the space industry in Kiruna employs 500 people right now. “If we can double that in 10 years, it will be a great success,” she says. “We know the mine will not be there forever.”

To my surprise, those least excited about the arrival of space tourists were members of Kiruna’s scientific community. Esrange, Sweden’s rocket range and the heart of Kiruna’s space industry, sits about 30 miles outside of town, along a snow-covered road that passes through mile after mile of pine forest. Just after dawn—which is to say, at about 8:45 in the morning—I gingerly turn along a sharp bend just in time to see a trio of reindeer plow through the snow on the side of the road and head into the woods.

Finally I climb a low hill and arrive at a security gate. Beyond it is a boxy building topped with telemetry antennas and radomes. Today, Esrange, which stages between 5 and 10 launches per year, is the European Space Agency’s primary site for lofting research rockets. Esrange itself is more of a launch pad than a lab; the staff specialize in getting other people’s experiments into space, or at least high into the atmosphere, whether it’s on rockets or balloons. Center scientists and engineers have built and launched eight satellites, including a space observatory (ODIN) and Sweden’s first satellite, VIKING, which was designed to study the aurora. They’ve also launched more than 550 balloons carrying atmospheric experiments—as well as astronomical instruments that need the clear skies of the upper atmosphere—as high as 24 miles above Earth. Nearly 35 Esrange-launched polar-orbit communications satellites make a total of 150 passes per day over the space center. “We started suborbital flights in 1966,” says Bergström-Roos. “We have all the infrastructure you need for communication with spaceflights.”

Esrange’s isolation makes the site ideal for rocket launches. The payloads parachute to Earth, landing on the 3,240-square-mile range, and within an hour are delivered by helicopter to researchers. At the peak of their suborbital flights, the range’s MAXUS and MASER rockets offer between seven and 13 minutes of near-weightlessness. Payloads are usually physics, chemistry, or biology experiments, some weighing up to 2,200 pounds. The constant, dry cold creates snow that’s almost dusty, so satellite dishes and buildings are clear of ice.

The day I visit, the space center’s restaurant is packed with students from all over Europe learning the rules for their balloon and rocket experiments. At the buffet line, Bergström-Roos introduces me to Lennart Poromaa, a gray-haired Swedish engineer who has spent nearly 24 years sending rockets and balloons up from Esrange.

Poromaa has doubts about sending up regular manned flights like the ones Virgin has planned. As a trio of Poles chat at one end of the table, I ask Poromaa if he would take a ride into space if money were no object. For a man whose job is sending million-dollar experiments skyward on a regular basis, Poromaa is remarkably uninterested. “In sounding rockets, you don’t have any people,” he says. “What we are dealing with, if we have a failure, a lot of money is lost but we don’t kill anybody. You can’t use a destruct charge if you have people on board.”

Next to him, Bergström-Roos cringes a bit. Poromaa shrugs: “I know too much about the risks. I would not be the first one to go,” he says, finishing his chicken. “You can never say never, but…”

When the first people fly into space from above the Arctic Circle, they’ll take off from Peter Salomonsson’s airport. From his first floor office, overlooking Kiruna’s snow-covered runway, the airport manager can easily keep an eye on the three flights that take off and land here each day, mostly connecting flights from SAS’s hub near Stockholm.

As long as the runway stays cold, ice isn’t a problem. “When it’s very dry and very cold, we have very small problems to land aircraft at Kiruna,” Salomonsson says. Virgin’s six-passenger SpaceShipTwo, last year christened Virgin Spaceship (VSS) Enterprise, would lift off from the runway with the help of a mothership, and glide back to the ground and land in the same place.

Like many of the Kirunans I met, Salomonsson has a knack for turning what some might consider the town’s weaknesses into selling points. He even counts the lack of air traffic above the Arctic Circle as one of Kiruna’s competitive advantages. “We have lots of free slot time,” he says. “Ten hours a day you can fly other things, like spaceflights.”

Pulling on a green wool hoodie, Salomonsson leads me to his car. We weave through the airport to the back door of his pride and joy: the Arena Arctica, a vast hangar big enough to swallow a 747-400, with room to spare. The Arena was built in 1991 to host research flights and cold-weather testing for Boeing. Since then, Airbus, NASA, and Eurocopter have all put aircraft through their paces in Kiruna, and the hangar has served as home base for atmospheric research flights.

Inside is a decommissioned Soviet Myasishchev M-55 spyplane capable of reaching altitudes of more than 70,000 feet. Even with its 122-foot wingspan—just a few feet shorter than Virgin’s mothership—the craft looked small in the 70,000-square-foot hangar. Heated concrete floors can keep airplanes warm overnight in bad weather, so there’s no need for constant de-icing. With creative parking, Salomonsson says, the airport has managed to fit two 737-800s, one MD-80, two Gulfstreams, and a Learjet inside.

The airport and the arena are critical parts of Kiruna’s appeal for Virgin and other commercial spaceflight operators. Spaceport America, near New Mexico’s White Sands Missile Range, is being built from scratch, but Kiruna’s infrastructure is already in place. In the last few years, Salomonsson has hosted execs from Virgin several times. Last year, Virgin Galactic President Will Whitehorn and a few dozen space tourists on the company’s waiting list visited Kiruna, where they met local dignitaries (including mayor Stålnacke and members of the Swedish royal family), spent a night in the IceHotel, and toured the Space Research Institute. The airport and the arena were a key stop on the itinerary. “When they arrived, they loved what they saw,” Salomonsson says. “The infrastructure’s already there, so we don’t have to build new from the beginning.”

Whitehorn declined to be interviewed, telling me via e-mail that Virgin Galactic was focused on making a New Mexico launch happen before discussing plans to fly from anywhere else. When pressed, he noted Kiruna’s “unique” attractions: a breathtaking view of the Arctic land and sea, and the Aurora Borealis.

Is it safe to send tourists hurtling through the aurora? Since the phenomenon results from space-borne particles hitting Earth’s upper atmosphere, a short flight through it won’t expose passengers to more radiation than astronauts on the International Space Station absorb in a similar six-minute period. “I would not think it would be dangerous,” says geophysicist Nikolai Østgaard, an aurora researcher at the University of Bergen in Norway.

A bigger question is whether there will be anything to see. The aurora may be best seen from below, where the light created by columns dozens of miles tall appears as a solid wave. “It’s going to be very exciting to see the light they’re flying into, but in a six-minute flight I don’t know what the chances of hitting it are,” Østgaard says. “The aurora moves like curtains, at a couple of hundred meters per second.”

Since announcing Kiruna as a possible spaceport, Virgin Galactic has been tight-lipped about its plans. Lots needs to happen behind the scenes, including regulatory approval from the United States (which may have concerns about exporting technology with potential military applications) and Swedish authorities. In Kiruna, Swedish pragmatism is keeping everyone from counting their space tourism dollars until they see flights take off in New Mexico. “If they are successful in New Mexico, they will come to Kiruna, we hope,” says Stålnacke.

Kiruna’s ready. Through some trick of the imagination, people here seemed to have turned everything I initially imagined as a liability into an asset. Throw in a healthy dose of cautious optimism, and you have the makings of the world’s northernmost spaceport.

Andrew Curry is a writer based in Berlin, Germany. This is his first article for Air & Space/Smithsonian.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1604_Danube_Contribs_02.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1604_Danube_Contribs_02.jpg)