The Spacewalk From Hell

While everyone else was marveling at the first free flight from the shuttle, Bob Stewart was in a world of hurt.

:focal(959x859:960x860)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/51/b8/51b891f9-0125-4ce7-9a8e-7c8e01cf1cc9/s84-27035_large.jpg)

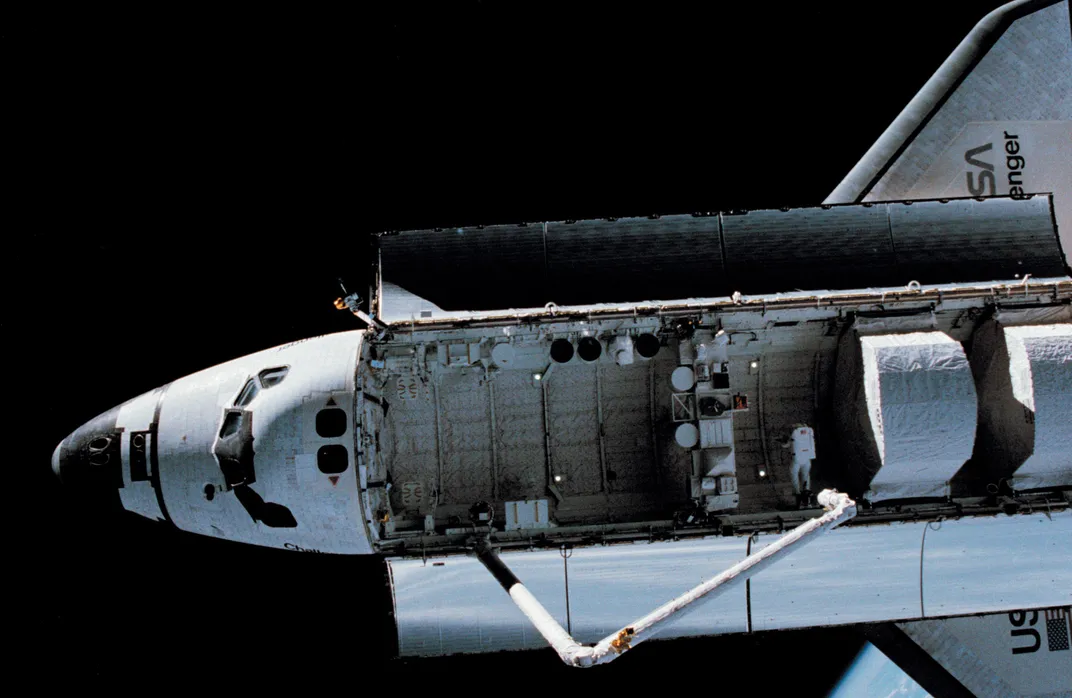

A spacewalk in Earth orbit—any spacewalk—requires working in a deadly vacuum for six hours in a stiff spacesuit. It’s an exhausting physical and mental challenge, and that’s if everything goes well. But when Bob Stewart ventured outside space shuttle Challenger with Bruce McCandless on February 7, 1984 to test NASA’s Manned Maneuvering Unit (MMU) “flying backpack” on mission STS-41B, he had no idea how jinxed a spacewalk could get.

The trouble started before the astronauts even opened the hatch to go outside. As the air vented out of the shuttle airlock, Stewart followed standard procedure, yawning to equalize the pressure between his middle ears and the spacesuit atmosphere of 4.3 pounds per square inch. That simple action broke the snap on the chin strap holding his communications carrier—the familiar cloth “Snoopy cap” worn inside the helmet.

“Now the chin pad on the strap floated up in front of my eyes…the worst possible place for it to be,” Stewart recalls. He pursed his lips and blew, bouncing the strap between his nose and the helmet surface. “As it came by, I grabbed it with my tongue and started stuffing it down inside the [helmet neck ring] to keep it from getting in my way.”

While he was busy giving the strap a tongue-lashing, Stewart didn’t notice that his Snoopy cap, which normally fit snugly, was riding up his head, taking his microphones and headphones along with it. “The first time I found that out was when I felt pressure on my ear lobes. Then I looked up…the mikes by this time were up at nose level,” instead of bent down toward Stewart’s mouth where they were supposed to be.

“I slammed my head on the back pad to keep the carrier from crawling off,” he says. Now he had an even bigger worry. “I did not want the ground to know about this problem, because they might cancel the EVA.” While Challenger was out of touch with Mission Control, he told McCandless and commander Vance Brand, inside the shuttle, what was happening. “We talked it over and I decided that I wanted to go. So Vance said, ‘OK, we’ll go.’ We went outside the airlock with my head stuck into the back pad to keep the comm carrier from coming off.”

He knew that spacewalking with his head jammed against the back of his helmet wouldn’t be fun, but the former Army test pilot and veteran of hundreds of Vietnam helicopter gunship missions thought he could tough it out.

As McCandless donned the MMU for history’s first “untethered” spacewalk—one of the most dramatic moments of the shuttle era—Stewart set to work in the payload bay. “I went to do my first task…and I could not get into the foot restraints. I could get my toe into the loop, of course, but I could not rotate my heel under the heel locks.” He couldn’t see it, but the outer fabric on his boots had slipped down over the heel cleats, preventing him from locking into the foot platform. “That meant I had to anchor myself in place with my left hand, which now takes away half my tools. And I’d have to react against all the torques I’m generating through my arms, rather than my feet. It was unbearably painful, with cramps in my arms.” Asked what was his frustration level, on a one-to-ten scale, he says, “Oh, man, it was about nine and a half.”

Meanwhile, Mission Control was on the radio loop with the free-flying McCandless, who was describing the stupendous views from his perch above the cargo bay. Then they turned to his spacewalking partner. “Bruce, we’ve heard enough from you. Bob, how are you doing?” Stewart’s voice-activated mikes were now up around eyeball level. “So I scream at the top of my voice…‘Oh, I’m doing fine! Let’s talk about it later.’ ” What he really thought was, I’ve got a problem with the suit, but I’m dealing with it. Leave me the hell alone.

The ground did not take the hint.

The strain of shouting while breathing the dry, pure oxygen inside the helmet had parched Stewart’s throat. But he dared not dip his chin to sip water from the straw on his neck ring: “If I moved my head to get to the water bottle, I’m going to lose the comm carrier. And I know where it’s going to go—right in front of my face.”

While McCandless continued his magic carpet ride, soaring as far as 300 feet from Challenger, Stewart faced his next problem. The sublimator in his spacesuit backpack, which chilled the water circulating through tubes in the cooling garment next to his skin, became choked with ice. The checklist attached to his suit cuff advised setting the suit temperature control to full cold. “That puts maximum cold water around your body so its heat can melt the ice in the sublimator,” he explains. “Well, when I turned that thing on full cold it was just like jumping into the Arctic Ocean. I could not turn that thing back to ‘hot’ fast enough!”

Now winging it, since there was no more advice from the checklist, Stewart thought he could clear the blockage by turning off the suit’s fan and water pump, cutting the water flow so the ice could sublimate away into vacuum. With the fan off, however, carbon dioxide levels in his helmet began to rise. When he sensed his breathing deepening in response, he flipped the fan back on. For the rest of the spacewalk he endured half a dozen of these freeze-ups, the last just as he was returning to the airlock.

“It was a very frustrating EVA,” he says, in a masterpiece of understatement.

Two days later, the spacewalkers went outside again, and this time Stewart would get to fly the MMU himself. While suiting up, he “put on the comm carrier, then took some medical tape…and wrapped it round and round my head to keep the [Snoopy cap] somewhat under control.” He still couldn’t use the foot restraints, but “postflight we figured out that the thermal micrometeoroid garment [TMG] on my suit slipped down over the [boot] heel tracks” and the engineers came up with a straightforward fix so future spacewalkers wouldn’t suffer the same problem.

Stewart found flying the MMU a test pilot’s dream. He gave the jet pack a top handling rating, “the only flying machine I have ever thought about giving a ‘1’. The only way you could make the MMU any easier to fly would be to wire it directly into your brain, so you only have to think about [executing] a maneuver. It was just a delightful machine…”

“While I was out there looking at the orbiter and looking at Earth, I got to thinking: ‘What would it be like to be the only person in the universe?’ So I turned the MMU to where I couldn’t see the Earth, moon, or sun—I could only see the blackness of space.”

“I only lasted about fifteen seconds, and I thought, ‘Well, let’s just turn around and make sure everything’s still there.’ That was an interesting feeling that I did not expect.”

It was a well-earned treat after one of the worst first spacewalks any shuttle astronaut could ever have.