The Spirit of St. Louis Lands Again

Charles Lindbergh’s iconic aircraft undergoes restoration.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/89/c7/89c75d9e-35ee-4ad5-923d-c5a982cfb43f/16a_jj2015_nasm2015-00294_live.jpg)

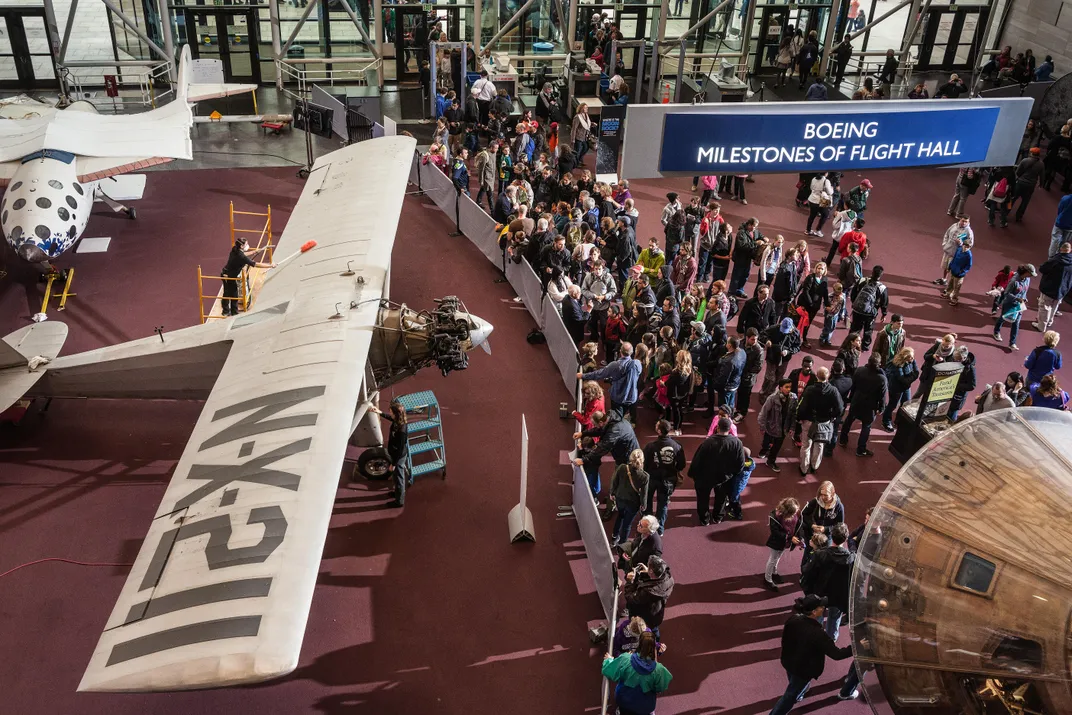

Last January, one of the National Air and Space Museum’s most famous treasures, which had been suspended from the ceiling for 22 years, was lowered to the Museum floor. Its temporary location “gives our visitors a wonderful opportunity to see this remarkable aircraft up close in a way that normally they will not have a chance to,” says curator Bob van der Linden. “It’s a very rare opportunity.”

The aircraft is undergoing preservation work for several months and will be suspended once again as part of the refurbishing of the Boeing Milestones of Flight Hall.

Charles Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis made their final flight together on April 30, 1928, when the famed aviator traveled to the Smithsonian Institution to donate his Ryan NYP.

Four hours and 58 minutes after leaving St. Louis, Lindbergh landed the Spirit at Washington, D.C.’s Bolling Field. After taxiing to a hangar door, Lindbergh sat quietly for a moment. According to the Chicago Daily Tribune, he then gathered a blue sweater and some baggage and stepped out of the airplane. “Lindbergh walked slowly around it, looking it over. He said the plane had flown more than 40,000 miles, and could ‘carry on’ that far again.”

The iconic aircraft has been displayed ever since, initially in the Smithsonian’s Arts & Industries Building, then in the National Air and Space Museum when it opened in 1976.

The recent lowering could be described as anticlimactic, says van der Linden, who adds, “Thank goodness! The last thing you want is excitement when you’re lowering the Spirit of St. Louis.”

During the lowering, van der Linden spoke with head conservator Malcolm Collum about the gold finish on the aircraft’s cowling. “We had always assumed that we were going to reverse it,” says van der Linden, “that it was essentially lacquer that we had put on. But Malcolm told me that Ryan Airlines added the varnish. Although it didn’t appear golden in 1927, it is historically correct.”

“A lot of this is tied to the metallurgy of the time,” explains Collum. “Back in the 1920s, aircraft were made of duraluminum, which is a way of making a nice malleable and strong aluminum alloy. But the biggest drawback is that it’s very susceptible to corrosion. Any exposed aluminum surfaces were always painted with a clear lacquer or paint coating for corrosion protection. These lacquers are very susceptible to light degradation, so over the years they will start to become more brittle and they will turn a beautiful golden, almost bronze color. And that’s the color you see today.”

While the varnish won’t be altered, other items on the cowling will be stabilized. After his 1927 solo transatlantic flight, Lindbergh took the Spirit on a tour of the United States and Central and South America. Flags of the countries he visited were painted on both sides of the cowling.

“Under each flag there’s an indication of when he landed and the city in which he landed,” says Collum. “Every flag is painted by a different person, and they used a different kind of paint and a different lettering style. Each flag has its own unique character.

“But over time,” says Collum, “some colors have faded more than others, depending on what kind of pigments were used by that particular artist. Some of the flags have very badly color shifted. So a yellow strip in a flag will now look like a dark brown. Dealing with that is one of the bigger challenges. The goal of this treatment is to stabilize and preserve as much as possible. So if we see paint that is cleaving off the surface and is going to be susceptible to routine dusting and cleaning, then we’ll go in with a synthetic resin and try and stabilize those areas. We will not be repainting anything.”

Conservators are also evaluating small tears in the fuselage fabric. In the past, explains Collum, if the Museum had a historic airplane that had a tear in it, they would repair it according to the methods that maintenance crews would apply to a flyable airplane, so that the fabric would be strong and meet a variety of performance characteristics.

But conservators noticed a side effect of the repairs that were done 22 years ago, when the aircraft was last worked on. Says Collum: “The process of brushing new dope onto the surrounding, original dope has actually caused collateral damage to the peripheral areas. So we’re now looking at using an adhesive that is not only going to be reversible but also is not going to cause additional collateral damage as it ages.”

The staff has been surprised by a number of subtle details that are evident only in a close viewing. “There’s a gap between the control surfaces,” says Collum. “That hinge gap was originally covered with fabric. When it left the Ryan Aircraft factory, they had all those seams covered up with fabric as a way of helping with the streamlining. And then at some point—I think it was in New York—if you study the photographs, you can see [the fabric coverings are] there one moment, and then in another photograph they’re all gone. Someone went in and tore them all off. We can still see the witness marks in the dope where there was pink-edged taped fabric covering all of the gaps. So for some reason, perhaps it was interfering with the operation of the control surfaces, somebody tore it off all the ailerons and the elevators.

“That’s really the amazing thing about this airplane: It’s so untouched. Even though it has had a bunch of repairs, it’s still an incredibly original airplane.”

The Museum tentatively estimates that the Spirit will be on the floor through July.