Stay Tuned

A new emergency warning system will be tested on Wednesday — 60 years after another radio network warned Americans of Cold War air raids.

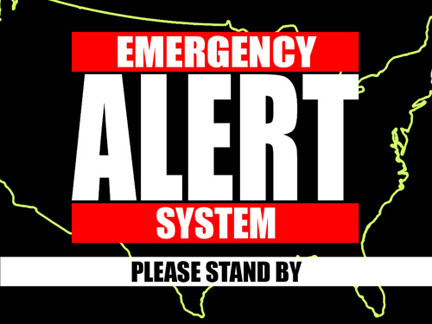

For 30 seconds beginning at 2 p.m. Eastern on Wednesday, November 9, every television and radio station in every U.S. state and a few of its territories, both broadcast and cable, will offer different programming than usual. Wednesday’s message will be continuous whether by audio, video, or digital stream: This is a Test.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has assured the public that “it’s not pass or fail.” It’s simply the first nationwide trial of the emergency alert system (EAS).

That system has been tested on a local basis every week for the last 15 years, when EAS replaced the emergency broadcast system. But it’s never been tested simultaneously from shore to shore. For one thing, it takes a lot of coordination: from the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) National Weather Service. Weather alerts, unsurprisingly, have comprised most of the genuine, local uses of EAS.

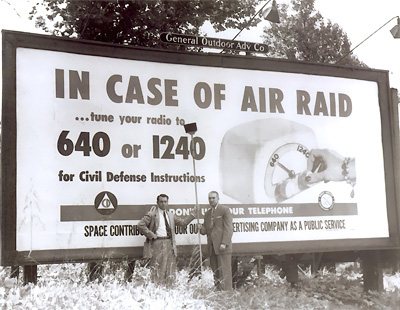

But EAS’s roots are not in storm warnings. Sixty years ago, a national system, CONELRAD (Control of Electromagnetic Radiation), was established in case of an air raid during the Cold War. Before CONELRAD, urgent news arrived by telephone or teletype machine to radio stations and fledgling TV networks, where a bulletin was typed in haste and handed to an announcer to read breathlessly on air. In March 1951, an FCC study recommended to President Harry Truman that “basic key stations” of the air defense command (ADC) and select radio stations reserve a special phone circuit and radio frequency to ensure a uniform and sober distribution.

On December 10, 1951, CONELRAD went live on two positions of the AM dial, 640 and 1240 kHz. It was tested nationally for the first time in the wee hours of September 16, 1953. By the summer of 1956, nationwide tests ran as long as 15 minutes and included a selection of tunes by the Air Force Symphony Orchestra. Almost from the start, though, the system gave false alarms from poorly wired connections or even lightning. Once a station on the CONELRAD circuit began transmitting, all other radio stations were to power down.

Commercial radio stations were often based in the center of cities, with their broadcast towers sitting atop the tallest available structures, making a natural bulls-eye for an enemy bomber to home in on its signal. To prevent such radio range finding, all stations other than the ring of CONELRAD transmitters were to temporarily cease broadcasting. Only brief bursts of emergency instructions were issued to prevent enemies homing in on the CONELRAD sites, which were nonetheless set well away from population centers.

Until 1963, the FCC required all radios sold in the U.S. to carry a mark reminding listeners where to tune in for civil defense instructions. Under CONELRAD, the small triangular CD or civil defense mark was also sold in a kit to glue onto the dials of older radios. When the national test transmits this week, we’ll see how that old technique compares to today’s digital reach.