Steinbeck’s Dispatches From Vietnam

In 1966, the author of The Grapes of Wrath met a new working class: Hueys, Hercs, and Spooky.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/SteinbeckFlash.jpg)

In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson asked John Steinbeck to visit South Vietnam and report to him personally on U.S. operations. (Steinbeck’s third wife, Elaine, and Lady Bird Johnson had been friends at college, and the Steinbecks were frequent visitors to the White House.) Steinbeck was reluctant to go to Vietnam on behalf of the president, but when the Long Island daily Newsday suggested that he travel throughout Southeast Asia as a roving reporter, he accepted. By that time, his two sons were serving in the Army. Between December 1966 and May 1967, Steinbeck wrote 86 stories for the newspaper. Those columns—collected in a book by the University of Virginia Press titled Steinbeck in Vietnam—were the last work to be published during Steinbeck’s lifetime.

December 31, 1966, Saigon: Remember how the lordly jet cuts its engines at 35,000 feet and floats gently toward the earth like Mark Twain’s polyhedron on lonely pinion? Well, that’s not the way you land in Saigon. Your friendly pilot pulls the plug and scuttles down like Walter Kerr leaving the theater or water making an exit from a bathtub. I guess he figures that the quicker he gets in, the less chance he has of taking a hit from a [Viet Cong] crossbow.

[Ca. January 1967/Vietnam]

Did you know that the airport at Saigon is the busiest in the world, that it has more traffic than O’Hare field in Chicago and much more than Kennedy in New York—Well it’s true. We stood around—maybe ten thousand of us all looking like overdone biscuits until our plane was called. It was not a pretty ship this USAF C-130. Its rear end opens and it looks like an anopheles mosquito but into this huge anal orifice can be loaded anything smaller than a church and even that would go in if it had a folding steeple. For passengers, the C-130 lacks a hominess. Four rows of bucket seats extending lengthwise into infinity. You lean back against cargo slings and tangle your feet in a maze of cordage and cables.

Before we took off a towering sergeant (I guess) whipped us with a loud speaker. First he told us the dismal things that could happen to our new home by ground fire, lightning or just bad luck. He said that if any of these things did happen he would tell us later what to do about it. Finally he came to the subject nearest his heart. He said there was dreadful weather ahead. He asked each of us to reach down the paper bag above and put it in our laps and if we felt queasy for God’s sake not to miss the bag because he had to clean it up and the hundred plus of us could make him unhappy. After a few more intimations of disaster he signed off on the loud speaker and the monster ship took off in a series of leaps like a Calaveras County frog.

Once airborne, I got invited to the cockpit where I had a fine view of the country and merciful cup of black scalding coffee. They gave me earphones so I could hear directions for avoiding ground fire and the even more dangerous hazard of our own artillery. The flight was as smooth as an unruffled pond. And when we landed at Pleiku I asked the God-like sergeant why he had talked about rough weather.

“Well, it’s the Viets,” he said. “They have delicate stomachs and some of them are first flights. If I tell them to expect the worst and it isn’t, they’re so relieved that they don’t get sick. And you know I do have to clean up and sometimes it’s just awful.”

January 7, 1967/Pleiku

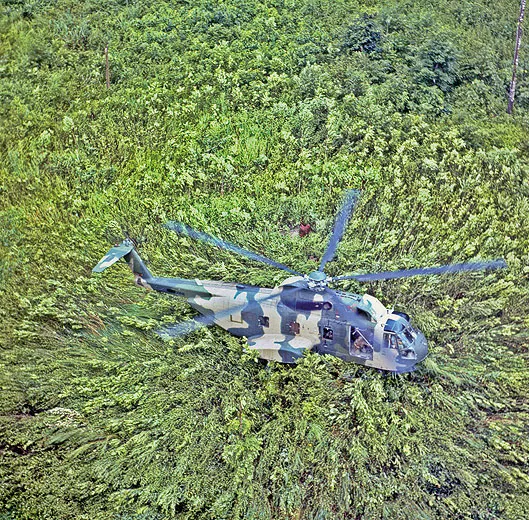

In my opinion the chopper is the greatest invention since the wheel. In eight days I have covered areas and put down in places it would have taken many months to visit on foot and that would be the only way to travel since there are few roads, and many of these are impassable, and what railroads there once were are cut and mangled by the fighting. I think I have traveled in every kind of chopper we have save one, or rather two. There is a single-place bubble I’ve missed because I can’t fly the thing, and I haven’t been on the giant Sky Crane, which looks like a huge dragonfly or praying mantis and which can take in its arms anything it can grip. It has transported a complete operating room with surgery continuing during flight. Eventually, when we have enough of them, the Crane will be of major logistical importance.

January 7, 1967/Pleiku

I wish I could tell you about these pilots [10th Cavalry, Huey helicopter]. They make me sick with envy. They ride their vehicles the way a man controls a fine, well-trained quarter horse. They weave along stream beds, rise like swallows to clear trees, they turn and twist and dip like swifts in the evening. I watch their hands and their feet on the controls, the delicacy of the coordination reminds me of the sure and seemingly slow hands of [Pablo] Casals on the cello.... You will gather that we are now in V.C. country, where every tree may open fire and often does. Maj. Thomas dips into a stream bed cascading down a twisting canyon and you realize that low green cover you saw from high up is towering screaming jungle so dense that noonday light fails to reach the ground. The stream bed twists like a snake and we snake over it, now and then lofting like a tipped fly ball to miss an obstruction or cutting around a tree the way a good cow horse cuts out a single calf from a loose herd.

February 2, 1967/Saigon

Soon after I arrived in South Vietnam, I became aware of the constant presence of slow, low-flying, fixed wing, single engine airplanes that coast and cruise about, circling and quartering. And it wasn’t long before I began to hear about the F.A.C. or Forward Air Controllers. They are among the bravest and the most trusted and admired men in this shattered country, and to the enemy, the F.A.C. must be about the most feared. I had heard many stories of their duties and their accomplishments and just a day ago I was allowed to fly with one on three separate and different missions, and it was an experience I will not soon forget.

As usual it was an early trip through the roiling traffic of Saigon to the 120th Helicopter Operations at Tan Son Nhut Airport. It gets light late this time of year. At 0710 it was still dawn. Then there was the quick and businesslike chopper trip to My Tho in the Delta district. At breakfast I met my pilot, Maj. William E. Masterson, called “Bat” of course, the Forward Air Controller for the Seventh ARVN Division, a strong good looking officer with a very knowing and humorous eye. He was a B-52 pilot who volunteered for FAC. Indeed, I may be wrong, but I believe all FAC pilots are volunteers.

Our aircraft was an O-1 “Bird Dog,” a single-engine, propeller driven, fixed wing Cessna which moves at 90 to 100 knots and has two seats, one behind the other. It is the same aircraft you see all over America, a slow, dependable job with fixed landing gear, fairly safe if its single engine is properly maintained. Our craft carried four rockets on the wing tips, two M-16 carbines, hand operated and mainly for self-defense in case of a forced landing, and a number of smoke bombs for signaling and marking.

We had no parachutes. They would take up too much room and flying as low as the FAC fly—anywhere from 200 to 2,000 feet, you couldn’t get out in time anyway. We did wear the armored vests which are said to take the sting out of small arms fire.

Major Masterson, Bat, said, “They don’t shoot at us much because we can call in an air strike in a few minutes and snipes just don’t want to take the chance. But if we should get hit, I’ll set down easy if I can and then we pile out and hit for cover with the M-16s and wait for rescue.”

I was pretty clumsy getting into the back seat with the thick vest on, and butter-fingered getting the belt and shoulder straps tight. There was no fooling around. The prop soared and brought the oil up to pressure. On the edge of the airstrip a ground man pulled out the pins from the rockets arming them and passed the pins in to me.

The little ship danced down the runway and jumped into the air. I had earphones and a mouthpiece for communication. Our first mission was visual reconnaissance, called naturally VR, and it is unique and fascinating work. Each FAC man has a sizable piece of real estate for which he is responsible. He flies over it every day and sometimes several times a day. He gets to know his spread like the back of his hand and he looks at it so closely that he is aware of any change, even the smallest.

I asked what Bat looked for. “Anything,” he said, “absolutely anything.” We were flying at about 500 feet. “See that little house down there? The one right on the river edge.”

“I see it.”

“Well, I know four people live there. If there were six pairs of pants drying on the bushes, I’d know they had visitors, and maybe V.C. visitors. Look at the next place—see those two big crockery pots against the wall? I know those pots. If there were three or four, I’d investigate. Oh! Oh!” he said and swung suddenly in over the paddies away from the river. About ten water buffalo were grazing, standing in the watery field. Our bird dog swung low and the beasts raised their heads at us.

“V.C. transport,” said Bat. “See, how thin they are? They’re working them hard at night.” He made notes on the detailed map on his lap. “We’ll flare tonight and maybe catch them moving.”

“Tell me some other things you look for,” I asked.

“Well, there are so many things I don’t know where to start. Too many water plants torn loose. Lines in the mud on the canals or the riverside where boats have landed, trails through the grass that have been used since yesterday. Too many people in one place or not enough people where they should be. We spotted a flock of Charleys because one pair of blue jeans was hanging on a peg in a house where there shouldn’t be blue jeans. Sometimes it’s too much smoke coming from a house at the wrong time. That means they’re cooking for strangers. I can’t begin to tell you all we look for. But sometimes I don’t even know what it is I’m seeing. I just get a nervous feeling, and I have to circle and circle until I work out what it is that’s wrong. You know how your mind warns you and you don’t quite know how.”

“Like extrasensory perception?”

“Yes, I guess something like that,” he said.

We followed the river down to the sea and then moved along the beach south and eastward to where the Marines had recently landed. Their beachhead was manned and we turned inland and swept right and left until we found the advance force moving painfully through the flooded muddy country, all mangrove swamp and nastiness. Masterson talked to the ground. “I can’t see anything up ahead,” he told the weary command. “But don’t take my word. You know how they can hide.”

“Don’t we just!” said the ground. We swung back toward the river quartering the country like the bird dog we are named for. On a canal ahead, a line of low houses deep in the trees was slowly burning, almost burned out. “Ammunition dump,” said Bat. “We got it yesterday. Must have been quite a lot from the secondary explosion we got. Have to go back to refuel now. We’ll have a bite of lunch and then we’ve got a target, I think a real good one.”

Not very long afterwards we dipped down on the little airstrip as daintily as a leaf and taxied in. I handed the pins out the window and the ground man stuck them into the holes that disarmed the rockets. And then we drifted to a fueling place and I edged my way out of my seat. The ground was a little wavy under my feet.

February 25, 1967/Saigon

It was my last night and I had reserved it for a final mission. Do you remember or did I even mention Puff, the Magic Dragon? From the ground I had seen it in action in the night but I had never flown in it. It was not given its name by us but by the V.C. who have experienced it. Puff is a kind of crazy conception. It is a C-47—that old Douglas two-motor ship that has been the workhorse of the world since early on in World War II.

The one I was to fly in was celebrating its 24th birthday and that’s an old airplane. I don’t know who designed Puff but whoever did had imagination. It is armed with three six-barreled Gatling guns. Their noses stick out of two side windows and the open door. And these three guns can spray out 2,800 rounds a minute—that’s right, 2,800. In one quarter-turn, these guns fine-tooth an area bigger than a football field and so completely that not even a tuft of crabgrass would remain alive. The guns are fixed. The pilot fires them by rolling up on his side. There are cross hairs on his side glass. When the cross hairs are on the target, he presses a button and a waterfall of fire pours on the target, a Niagara of steel.

These ships, some of them, are in the air in every area at night and all night. If a call for help comes, they can be there in a very short time. They carry quantities of the parachute flares we see in the sky every night, flares so bright that they put an area of midday on a part of the night-bound earth. And these flares are not mechanically released. They are manhandled out the open door by the flare crew. I knew the technique but I have never flown a night mission with Puff. I had reserved it for my last night in South Vietnam. We were to fly at dark and hoped to be back by midnight.

I went by chopper to the field where the Puffs live, met the pilot and his crew and had supper with them. Our mission was not general call. A crossroad area had been observed to be used after dark recently by Charley, who was rushing supplies from one place to another for reasons best known to Charley. We were to be directed by one of the little F.A.C. planes I spoke of in an earlier letter.

Because it was hot and no wind in prospect, I wore only light slacks and a cotton shirt. We flew at dusk and very soon I found myself freezing. Puff is not a quiet ship, her door is open, her gun ports open, her engines loud and everything on her rattles. I did not wear a headset because I wanted to move about, so one of the flare crew, a big man, had to offer me an extra flight suit and he said it in pantomime. I accepted with chattering teeth and struggled into it and zipped it up. Then they fitted me with a parachute harness and showed me where my pack was in case of need. But even I knew that flying at low altitude, if the need should arise, there wouldn’t be much time to get out even if I were young and clever.

Forward of the guns and aft by the open door were the racks where the flares stood, three feet high, four inches in diameter. I think they weigh about 40 pounds. Wrestling 200 or 300 of them out the door would be a good night’s work. The ship was dark, except for its recognition lights and a dim red light over the navigator’s table.

They gave me ear plugs. I had heard that the sound of these guns is unique, so I put the rubber stoppers in my ears but they were irritating so I pulled them out again and only hoped to get my mouth open when we fired.

There was a line of afterglow in the western sky, only it was not west the way Puff flies. Sometimes it was overhead, sometimes straight down. Without an instrument you couldn’t tell up from down but my feet were held to the steel floor by the centrifuge of the turning, twisting ship. Then the order came and a flare was thrown out and another and another. They whirled down and the brilliant lights came on. We upsided and looked down on the ghost-lighted earth. Far below us almost skimming the earth, I could see the shape of the tiny skimming FAC plane inspecting the target and reporting to our pilot. We dropped three more flares, whirled and dropped three more. The road and the crossroads were very clearly defined on the ground and then there was a curious unearthly undulating mass like an amoeba under a microscope, a pseudo-pod changing in shape and size as it moved. Now Puff went up on its side. I did know enough to get my mouth open. The sound of those guns is like nothing I have heard. It is like a coffee grinder as big as Mt. Everest compounded with a dentist’s drill. A growl, but one that rocks your body and flaps your eardrums like wind-whipped flags. And out through the door I could see a stream, a wide river of fire that seemed to curve and wave toward the earth.

In May 1967, Steinbeck returned to the United States and told President Johnson what he’d seen. A second debriefing, to Johnson’s cabinet, is archived at the Department of Defense. Steinbeck returned to New York and on December 20, 1968, died of heart failure.

Copyright © 1965, 1966, 1967 by John Steinbeck; renewed Elaine Steinbeck and Thom Steinbeck 1993, 1994, 1995. Reprinted with permission of McIntosh & Otis, Inc. “Vietnam War: No Front, No Rear,” “Action in the Delta,” “Terrorism,” “Puff, the Magic Dragon,” from America and Americans and Selected Nonfiction by John Steinbeck, edited by Susan Shillinglaw & J. Benson, copyright © 2002 by Elaine Steinbeck and Thomas Steinbeck. Used by permission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.