Stowaways

The strange things restorers find in old aircraft.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/stowaways-0508-631.jpg)

Over the last half-century, the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration and Storage Facility in Suitland, Maryland, has restored some of the rarest and most important aircraft in history: a Northrop Flying Wing, the B-29 that bombed Hiroshima, a World War I-era Nieuport 28C fighter. The Garber complex has played as crucial a role in preserving aerospace history as its spiffier counterparts, the National Air and Space Museum on the Washington, D.C. Mall and the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Virginia. But in some ways, Garber is also like the Land of the Misfit Toys. Dark, dusty hangars house broken, battered pieces of equipment and aircraft waiting—often for years—for their moment to be brought back to life.

When the time comes, each aircraft is hauled out and taken apart, often down to the tiniest screw, and that is how the restoration team ends up discovering stowaways—unexpected objects hidden in nooks and crannies, sometimes dating back to the earliest days of the aircraft.

Depending on their relationship to the aircraft that hosted them, these accidental artifacts fall into three general categories.

Details That Tell the Tale

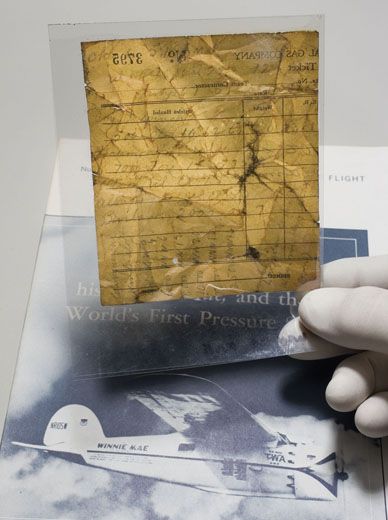

Sometimes the Garber restorers come across objects that help flesh out the story of the aircraft, much the way little details make a scene in a novel easier to picture. Museum Specialist Bob McLean came across such an artifact while helping to restore the Lockheed Vega Winnie Mae, renowned as the aircraft in which Wiley Post made the first two solo flights around the globe, in 1931 and 1933. The airplane had been donated to the Smithsonian in 1936, a year after Post had died. While in the cockpit, McLean stumbled on an oil-soaked scrap of paper. "At first I thought it was just a receipt," he says. "But if you look closely, you can make out [numbers signifying] winds aloft and stations out west." So far, it's not known whether the handwriting is indeed Post's.

In the case of the Museum's Martin B-26 Marauder, Flak Bait, the Garber restorers unearthed artifacts in it that serve as reminders of the bomber's unusually violent career.

Flak Bait survived a formidable 207 missions over Europe, more than any other U.S. aircraft during World War II. And it has more than 1,000 patched flak holes to show for it. But though it could take plenty of punishment from the Germans, it was intolerant of abuse from its own pilots. "It was considered a very dangerous aircraft to fly because it was so unforgiving," says Museum Specialist Matt Nazzaro. "It had very high wing loading and was very fast for a medium bomber. Any pilot who commanded one would swear by the airplane, but if you made one critical mistake, there was no forgiveness."

In the course of surveying Flak Bait, the Garber restorers uncovered several paper clock faces pasted on the bulkheads. Nazzaro believes these were used to orient crew members when they spotted an enemy aircraft. "If they were disoriented, they could just look at the clock and properly communicate where the enemy was: ‘Bandit at two o'clock,' for example."

When the restorers removed the rear fuselage cabin floor, they discovered four .50-caliber shell casings, marked with a 1942 manufacturing date. Nazzaro believes the bullets were fired "probably from the waist guns" of the bomber.

Flak Bait's entire floor was covered with 10-millimeter-thick armor plating. "It was like a high-grade-steel throw rug," says Nazzaro. "It slowed down the airplane because it was so heavy, but it was necessary to prevent flak from coming up through the floor and killing people." When they pulled up the armor plating, Nazzaro says, the restorers found "mud from airfields 50 years back under there."

They also saw wooden matches strewn everywhere, as well as automobile ashtrays riveted to the interior. "These guys were smoking their brains out," Nazzaro says. "After a dangerous mission like the ones they flew, wouldn't you?"

Details That Set the Stage

Some of the stowaways uncovered at Garber illuminate not the history of the individual aircraft but rather the time and place in which it served. Last July, intern Eric Lawrence was cleaning out a Curtiss F9C-2 Sparrowhawk, a small, airship-based fighter that the Navy used in the 1930s for reconnaissance patrols along the U.S. coasts. When he was working in the fuselage tail cone, Lawrence came across a broken pencil, inscribed with the words "Hoover for President, 1928."

Evocative items seemed to pour out of the sole surviving Japanese Aichi M6A1 Seiran, a World War II bomber designed to be stashed in a submarine, its wings folded, until the sub surfaced for launch. Allied forces discovered a Seiran at the Fukuyama training base after World War II and brought it to California on a U.S. carrier. It was eventually donated to the Smithsonian.

The restoration "was an unusually long project," says Nazzaro, lasting from 1989 to 2000. "It's probably the most accurately restored and one of the finest restorations of any Japanese World War II aircraft in the world. You get inside that airplane and you go right back to 1945."

During the process of removing, cleaning, and cataloging every bolt and rivet in the Seiran, a number of items turned up. "We scraped up the dirt in the bilge, filtered and cleaned it, and found these artifacts," says Nazzaro, holding up several tools and plastic bags filled with metal scraps. One of the tools is a hand-made bucking bar, which is placed on the other side of a piece of metal being riveted in order to dampen the shock of the rivet gun. "You can see an actual finger notch here," says Nazzaro, gripping the Seiran tool to show how fingers fit the bucking bar. "It was probably made for a small hand, maybe a woman or a student. That tells a story for me."

The metal scraps the restorers found in the Seiran are small and round and have sharp edges. "Someone probably realized he needed a hole drilled through a bulkhead but didn't have a hole saw," Nazzaro says. "He used a standard drill instead, and drilled 50 or so holes close together and then knocked it out. He didn't even bother to smooth the edges so it wouldn't cut whatever wires were passing through here. An American airplane would have had a rubber grommet around that hole."

In an inboard-wing fuel tank, restorers found inspection progress records, a worker time card, and a warehouse receipt.

Nazzaro believes the artifacts in the Seiran provide clues to the mood prevailing in wartime Japan. The material the restorers discovered, he says, shows "their urgency, how really desperate they were to get this flying. It speaks to the level of quality in their factories."

Mysteries remain. One of the forms had a handwritten note on it, which translates to "Yesterday's thought. Today's thought. There is no difference." Is that a sign of dedication and focus, or of demoralizing boredom?

Details That Don't Fit

And then there are the finds that no one can account for.

Beneath the pilot's seat of an elderly glider, a Bowlus 1-S-2100 Senior Albatross built in 1933, restorers found a linen handkerchief, delicately embroidered with flowers. Says Bob McLean: "It looks like something a wealthy person would have carried with them—but that's just my impression."

The American-made Albatross, named Falcon, had been donated to the Smithsonian in 1935 by the widow of Warren E. Eaton, who had flown SPAD XIII fighters in the 103rd Aero Squadron in France during World War I. After the war, Eaton founded the Soaring Society of America. Could the embroidered handkerchief have been given to him by a beloved family member, or by the object of his affections? At some point had a woman flown the glider? It's fun to imagine the possibilities.

A small medallion—discovered tightly crumpled around a screw in a World War II British Hawker Hurricane Mk.IIC fighter—also ended up teasing the restorers with possible storylines. Museum Specialist Will Lee, who found the medal while working on the Hawker restoration, took the time to straighten it out, make it recognizable, and do some investigating. "It's actually a watch fob," says Lee. In the course of researching the item, Lee learned the meaning of the medallion's icons: "The anchor symbol means it was made in Birmingham, England. The lion indicates that it's made of silver, and the letter corresponds to a date—in this case, 1915." But who had owned the medallion? A pilot? A maintainer? A person of wealth? And why was it wrapped around a screw?

Whoever the medallion's owner was, he may have had a sweet tooth: While working on the Hurricane, Garber employees also found a vintage candy bar wrapper.

The handkerchief from the Albatross and the pencil from the Sparrowhawk were both catalogued and attached to the aircraft's collections by their curators. Not all items discovered during the restoration process are classified this way. "It really depends on the mood of the curator," says McLean, "whether he has time to process the item and whether he even knows about it."

No matter what object the restorers find, even when they can't fit it into any kind of narrative, they take it seriously. They know that what looks like a piece of junk can be brought to life by the right insight. At Garber, a jagged metal scrap can serve as a small portrait of wartime desperation, and a dirty list of scribbled numbers can show the drive it takes to set a world record—twice.