Stratomouse!

In the 1950s, balloons carried live mice to near-space to study how the trip might affect astronauts

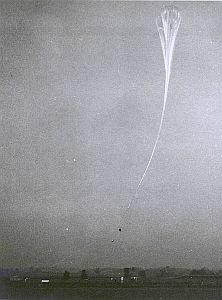

A gondola carrying live payload to be carried up to the stratosphere by balloon. Photo: Winzen Research Inc.

As the U.S. government was gearing up to send the first man into space in the 1950s, questions abounded as to how people would survive in this foreign environment: What kind of vehicle would best protect them? How should environmental controls be configured? Will people even survive the radiation levels, unprotected by the Earth’s atmosphere?

One way to prepare for the journey was to send biological material — plants and animals — to near-space on a balloon, with various instruments, and measure the effects. In 1955, doctor and writer Webb Haymaker followed around a Navy crew as they launched balloons from Minnesota and raced to recover the live payloads. He published the account in what was likely one of the more exciting articles to appear in the journal Military Medicine.

“Operation Stratomouse,” as Haymaker dubbed it, began with the biggest foil of balloon launches: the weather. The many last-minute “no-gos” finally started to turn the anxious crew members against each other. “Once, after a favorable forecast had ushered in utterly impossible weather, and a crew member had remarked that ‘that crowd of parasitic bandits over in the weather station ought to be sent up in one of the balloons,’ Lewis squelched him by commenting quietly that he would be dispatching them in the wrong direction!”

Mice, those perennial lab creatures, were among the payloads to be studied for any effect from cosmic rays. Project lead Otto Winzen noted that although they had “sent balloons up for many purposes, even some with rockets dangling from them which are fired into the upper stratosphere when the balloons reach 80,000 feet… the flights to come have a particular significance because of their living cargoes.”

And those living cargoes required special packing:

They were in a flat wire mesh cage, each in its own compartment, gnawing away on pieces of raw potato, which would quench their thirst on the long cruise. The cage was placed on the platform which covers the lower hemisphere of the gondola. Then the two hemispheres were sealed airtight by means of 134 bolts and nuts, and around the sphere went a thick shell of insulating plastic and over that a layer of shiny aluminum foil to reflect the sun’s rays. The oxygen tanks were strapped into place, and filled to capacity. The gondola purred from the vibration of its cooling fans like something alive.

While certainly risky for the near-space-traveling mice, it wasn’t always a safe venture for the human crew, either.

Evelyn A leaped skyward, giving off an agonizing, crashing, echoing sound. As she moved swiftly in the direction of the truck, a gust of wind caused her to hesitate; her long nylon rope then lashed out to one side in an undulating movement as though it were a whip being cracked. Agile little Herk Ballman, standing at the level of the beacon, just managed to jump out of its way. An old hand at balloon launching, he had always been successful at outwitting a rampaging balloon. His close call brought to mind a launching in Europe in which one crewman had had his scalp ripped from one end to the other by a rising gondola, and another his forearm mangled and his shoulder dislocated by a swerving nylon rope which had momentarily looped itself around his arm.

Once aloft, the 175 foot-diameter balloon was quite the sight:

“There’s something eloquent about a gigantic balloon when being launched, whether it slips away tranquilly into the unknown or goes charging forward like an enraged elephant,” Winzen went on to say. “Each has a personality of its own and every one is a solo performer. From where I stand on the launch platform, I can catch from one balloon the satiny swish of a wedding gown as a breeze twists it, and from another the full resilience of a four-master after it has lurched suddenly before a gust of wind.”

The team had a C-47 at their disposal to chase the balloon, which would travel hundreds of miles away, giving the gondola payload extended exposure to near-space. Meanwhile, calls of flying saucer sightings came pouring in to newspapers and even the FBI as the balloon floated over farms and nearby towns. But Haymaker was taken with the romance of the sight:

Brilliantly lighted by the setting sun, she looks like the evening star. A little later, having taken on a harvest moon hue, she is outshone by Venus. A pity that she is expendable! Tomorrow, after she has accomplished her noble mission, a segment of her wall will be ripped out by a line attached to the top of the falling parachute, and she will wallow and sink, like a harpooned whale, and ultimately be found in farmers’ refrigerators, reduced to vegetable bags.

The Navy boys were just as excited, but less moony-eyed, as one sergeant observed “that she is ’tighter’n a bullfighter’s pants,’ and should be belching off some gas soon.” Eventually, the gondolas were cut from the balloons and parachuted to the ground, where the crew frantically searched for it before time — that is, the oxygen — ran out. “They are looking for congregations of cows, who are curious about gondolas, and for a line-up of cars along a road, for farmers, too, take advantage of extraordinary diversions such as this.”

Sometimes it was good news, such as when the gondola from Evelyn A was recovered: “There they were, all 60 mice cocking their eyes at the warden and me as though asking for food.” Other times, it was total loss, such as when the gondola on Emma V didn’t sever properly, the payload clinging on far too long for the animals to survive. Emma V continued on its flight, making newspapers around the region as the crew tried anything to get it down:

Our Emma V was described as an unruly giant. The following morning the account was continued, the caption reading, ”Balloon Dips But Evades Plane Guns”… On the fifth morning there was this surprising announcement: ”Wandering Balloon is First Satellite.” The Emma V was sighted over Bathhurst, New Brunswick, and was headed over the Atlantic for ”a high-altitude European tour.”

Haymaker grandly concluded his story about the ballooners, championing their role in future spaceflight:

Up there, in the as yet hostile and forbidding fringes of space, where it is always night, the ubiquitous mouse has gained a foothold. Before man can do likewise, or, indeed, pierce the stratosphere and travel through the black unknown beyond, he will continue to need balloon-borne animals as forerunners-unless, per chance, man himself is willing to serve as “guinea pig” for his fellowman.