Student Aspirations, Public Excitement and the Purpose of a Space Program

What do young people want from the space program?

Recently I had the honor of giving two invited talks about space to college students. The first was a keynote speech for undergraduates at the annual Great Plains Honors Council regional conference (440 participants from 45 different educational institutions across six states), held this year at Lamar University. The other was a seminar for engineering and geology students at the University of Notre Dame. In both cases, I was struck by the fact that—based on their post-seminar comments, both written and oral—the students, though advanced in their academic studies, generally had not heard about the practical value and national strategic purpose in pursuing human missions beyond low Earth orbit. But they were quick to connect with the new information and possibilities.

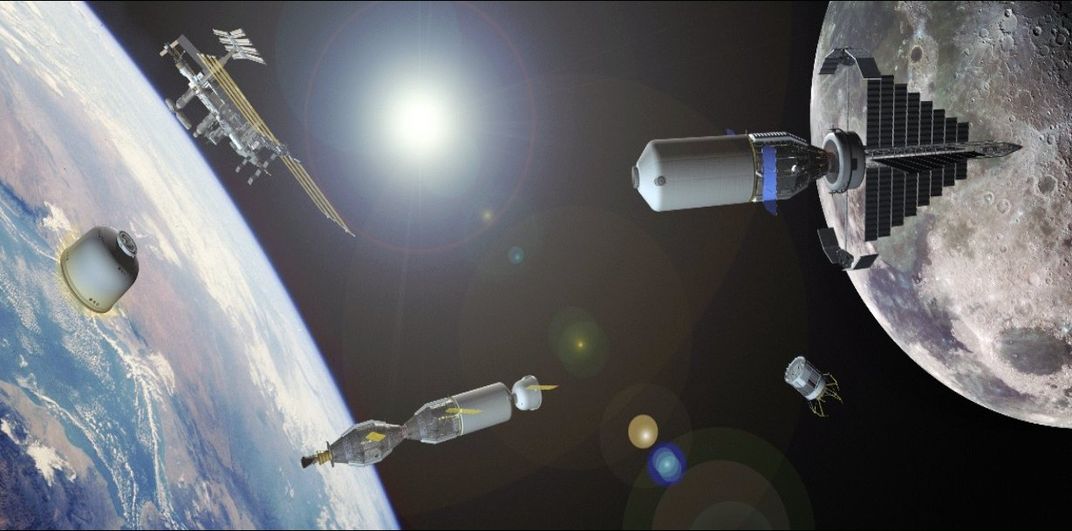

I advocate the outward expansion of operations in low Earth orbit—specifically, to cislunar space, the volume of space between and around Earth and Moon, where most satellite assets reside (video of a previous talk on this subject here). To do this we must build a permanent, space-based transportation system fueled by propellant made from lunar polar ice. Such a system allows routine access for satellite servicing and for construction of wholly new communications and remote sensing systems of superior size and capability. Developing such a space transportation system also permits human missions to the planets. In short, this plan offers a practical return and measureable value for expenditure. Envisioning how various academic disciplines had a place and value in those space endeavors, and realizing that practical, multifaceted returns can be made from investment in space was a light bulb moment for many.

The students were familiar with the usual rationales for the promotion of civil space—the “Journey to Mars” and robotic scientific probes. While the “dream is still alive” (i.e., the notion that space is a new frontier to explore and use), they also know that in today’s world, long-term projects requiring significant federal funding must navigate a maze of competing ideas and that their generation faces an already massive federal budget and debt. In such a contest, those who can show a concrete practical return on investment will have a natural advantage over those with a more nebulous return.

Of the lessons I took from this lecture, a major one was concerned with the necessity of one’s ability to convey the practical value of something. When presenting an idea to a group of people, such as Congress, they are not impressed by opportunities for science of grand future plans, instead they are concerned with what kind of practical or economic value can come from something.

One theme I emphasize in my talks is that, while space is expensive, it need not break the national budget. The key to success in such an effort is to: 1) know exactly what you are trying to achieve; 2) plan an incremental approach to that goal, using small pieces; 3) build in intermediate milestones at regular intervals to demonstrate progress. In many cases, it is the rate of expenditure that is critical, not the total aggregate cost.

I liked what he said about needing “early, recurring milestones for major objectives.” When you are trying to persuade people to invest completely in your idea, you need small benchmarks to build their confidence over time. This same plan should be used for engineers working with building owners and any other regulatory or funding body.

Several students were taken with the idea that the United States has a critical role to play in space. I explained that the emergence of a free market in space development is not a foregone conclusion, but rather depends on the willingness of the United States to be present and involved in future space economic activity, wherever it occurs. This argument is based on historical analogy—our nation believes in free enterprise, the rule of law, and a pluralistic political system, and we inculcate these values where we are involved.

The best way for the United States to respond to other countries’ space programs is simply to be there; to be in space and a part of a process so we have a say in what happens.

… More ominously, but perhaps more practically motivating, is the idea that a nation is either space powerful or space vulnerable—and those who are present make the rules. China, for example, has rapidly expanded their military-run space program. Though they do not pose a current threat, Dr. Spudis makes clear that this is no permanent truth—all of their missions thus far are “dual purpose.”

Many students understood my analogy of spaceflight to seafaring. The use of the world’s oceans by a wide variety of vessels has created a global civilization, one of trade and communications between all of humanity. As we move from LEO into the space beyond, we engage in voyages that last for weeks and months, instead of days. And as in seafaring, the new spacefarers require different vehicles and the supporting ports and re-fueling stations to permit this mode of travel.

I thought it was really interesting when he said that space exploration is not analogous with flight but rather with sea exploration. The term spacefaring sums this up well.

…We need to rethink what space travel can offer our world in terms of technological innovation and economic value. An analogy Mr. Spudis used was sea faring. Space is an unexplored ocean with untapped resources.

In addition to a new appreciation for the practical value of human spaceflight, most students instinctively view space as aspirational—a new and exciting theater of human endeavor to be engaged in and won. Building infrastructure and creating new wealth is all well and good, but our reach should always exceed our grasp. It is this challenge of new frontiers that engages people emotionally. Yet, interestingly, they didn’t seem primed for instant gratification nor “excitement”—requirements often cited as the necessary rationale to initiate new programs. Showing maturity, they saw the practical benefits of creating a long-term, cost-effective, permanent infrastructure.

I found this presentation very appealing. I was always very interested in space growing up and used to love watching the shuttle launches on TV. I was heartbroken when they stopped that program, but would love to see us expand our realms and attempt to maintain a presence in space. I was shocked how little his idea cost as well with respect to fitting within the current budget. I hope that some of his ideas receive backing going forward because going out into space and trying to do something useful makes sense given the eventual limited resources here on earth, the national interests mentioned, as well as it satisfies the natural human urge for curiosity and exploration beyond our own world.

… In the end, he proposes a new template for space travel and budget allocation—incremental, extensible building blocks that disperse comfortably into NASA’s yearly budget, extraction of material and energy from space to run the equipment located there, and only sending “smart,” information-dense materials up from Earth. Polar ice on the moon makes this a practical possibility—but it is up to my generation to make it happen.

The role of public opinion as an underlying support structure for our government space program is a topic that has received a lot of attention within the space community. The received wisdom is that a dynamic space program must “excite” the public in order to justify steady or increased funding for future projects. Although there is no objective evidence supporting this supposition, it is certainly true that in a democracy, long-term projects cannot be sustained for years and decades unless there is at least a modicum of popular support.

I always enjoy engaging with students because they help me put into perspective exactly how one segment of the public perceives and reacts to what is being done in space. The idea that there is no interest in a return to the Moon (“We’ve been there”) is simply not true, because this generation has never been to the Moon. But when shown the value of such an endeavor and how it contributes to our long-term posture in space and on Earth, they get it.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/blog_headshot_spudis-300x300.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/blog_headshot_spudis-300x300.jpg)