The Sultan of Speed

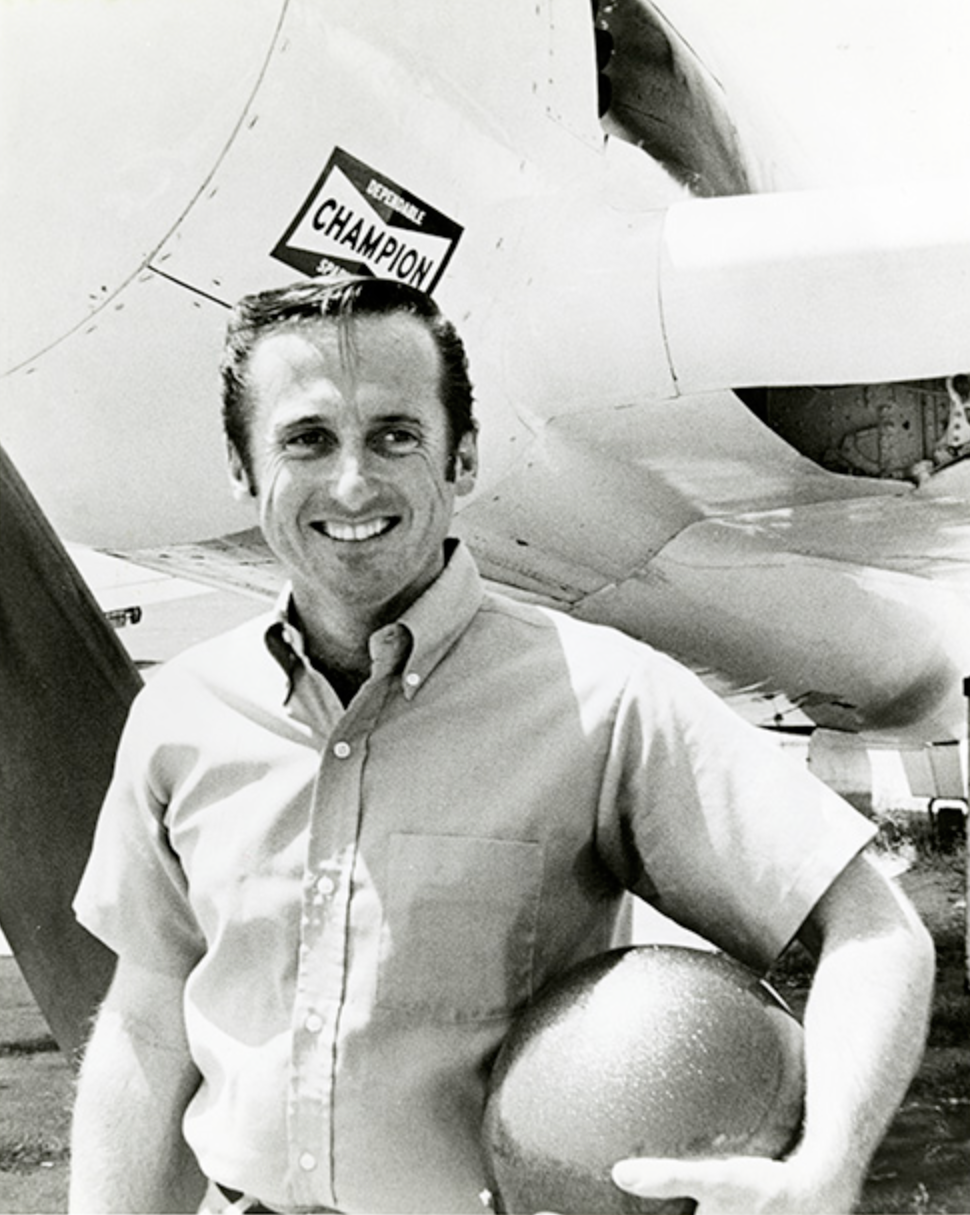

Remembering the irrepressible Darryl Greenamyer (1936-2018).

:focal(1773x548:1774x549)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/4d/214dce67-a9cc-4a5c-aa15-54b66f1a612a/greenamyer.jpg)

Darryl Greenamyer, who died October 1, was my hero. Not just mine, of course; he’s the hero of every aviation fan who’s been conscious in the last 50 years. But, just as a lot of airplane lovers choose their favorite warbirds (P-47 Thunderbolt), some also choose their favorite pilots. Greenamyer was about a decade behind the greatest generation of test pilots—Yeager, Hoover, Crossfield, Armstrong, Edwards—but he’s in the pantheon, and whereas those pilots gained fame in government-funded programs, Greenamyer, who got his start in the military, earned his reputation working for nobody but Darryl Greenamyer.

The world three-kilometer speed record for piston-engine aircraft had stood for 30 years when Greenamyer broke it in 1969, flying an average speed of 482 mph in his Bearcat Conquest I and reinvigorating the ambitions of race pilots for the next 50 years. In 1964, with a beat-up Grumman F8F Bearcat as bait, Greenamyer assembled a team of nonpareils from Lockheed, where he had been a test pilot on F-104s, A-12s, and SR-71s. One of the keys to the Bearcat’s speed was an engine cooling system that borrowed an idea from the F-104 and an application from the Messerschmitt Me 209, the airplane built to set the speed record in 1939. “When F-104 pilots dashed to Mach 2.2 to intercept an airplane, they had a special little heat exchanger in the environmental control system to help cool the air that was coming into the cockpit to cool the pilot and also the avionics equipment,” explains Pete Law, part of the Lockheed brain trust that Greenamyer recruited to assist in his effort at record-breaking. (While we’re talking, Law says forlornly, “I’m the only member of the crew still alive.”) The F-104’s heat exchanger was a water-boiling system, says Law, akin to the water-boiling system the Germans had used to cool the Me 209’s oil and engine coolant. Still at Lockheed, Greenamyer went to Ben Rich, then head of propulsion thermodynamics at the Lockheed Skunk Works (and later its director), to ask about designing a cooling system; Rich introduced him to Law. “Oh, yeah. I can design one of those,” Law remembers saying. Lockheed aerodynamicist Bruce Boland joined up at the same time, and the systems and modifications that the team introduced on the Bearcat later spread throughout the racing community and are still creating winners at the Reno air races today. In 1977, Greenamyer donated the airplane to the Smithsonian Institution National Air and Space Museum.

Besides leading his racing crews—his Bearcat took the championship five years in a row between 1965 and 1969 and again in 1971—Greenamyer was one of the hardest workers on the team. “He’s a hands-on guy, he’s not just stand off and call me when the airplane’s ready,” Bill Kerchenfaut told aviation photographer and writer Wayne Sagar in 1998. (Kerchenfaut, who died in 2016, was another of Reno’s legends. After getting his start with Greenamyer, he went on to become the winningest crew chief at the air races.) “He’s a superb mechanic,” Kerchenfaut said. “An excellent engineer.”

“He could do anything that needed to be done on the airplane,” said Law. According to family lore, Greenamyer started building his credentials as a mechanic early: when he was a toddler. Ready to be liberated from his crib one morning, he grabbed a screwdriver from a nearby window sill, unfastened screws on the crib’s four posts, and dropped himself to the floor.

Lockheed hired him right out of college in 1961—he had earned most of his credits toward a degree in mechanical engineering at the University of Arizona while he was flying F-100s with the Arizona Air National Guard—though Greenamyer has said he just kept showing up until someone finally told him, “You’re hired.” Three years later, still at Lockheed as a test pilot of F-104 Starfighters, SR-71 Blackbirds, and A-12s (the CIA variant of the SR), Greenamyer began accumulating parts to build his own F-104, planning to set the world low-altitude speed record even before he had taken the three-kilometer record from the Germans. As a Sports Illustrated reporter wrote in 1978, “Although he is a rare creature, Greenamyer is downright commonplace compared to the Red Baron, the extraordinary [F-104] he assembled with his own hands. If King Khalid of Saudi Arabia wanted a plane just like Greenamyer’s, he could not buy one, not for all the oil in his country….The Red Baron was truly one of a kind—and there will never be one like it because nobody, not even Greenamyer, is sure just where all the junk in it came from.” Pete Law knows where some of it came from.

At the time Greenamyer was putting together his own personal Starfighter, Lockheed was working on an export version of the Mach 2 interceptor with a high wing and gentler handling characteristics, the CL-1200. (The Starfighter had proved difficult for pilots who weren’t stars to fly.) Lockheed genius Kelly Johnson needed a nosecone for the airplane, and Greenamyer had accumulated several. In exchange for a nosecose, Johnson said, Greenamyer could spend 15 minutes with parts and pieces the company had cannibalized for possible use on the CL-1200. “So Darryl told me what he wanted and I went down and told the guys in charge of the mockup area,” says Law. “I set all the parts aside so Darryl could carry the stuff out and put it in his pickup truck.” It was a simpler time.

In 1977, after a first pass at 1,010 mph about 60 feet off the ground, Greenamyer flew the F-104 to set the low-altitude speed record, 996 mph. He felt pretty confident that the airplane could also steal the absolute altitude record from Russian pilot Alexandr Fedotov, who had that same year climbed his MiG E-266M to 123,523 feet. But on a practice run for the altitude record, Greenamyer couldn’t get the F-104’s gear lowered, despite six tries consuming 30 minutes of fuel, and, with the needle close to empty, he had to punch out, using the one component on an F-104 he had never tested. Minutes later, in pieces on the desert floor, lay 13 years of work and incalculable treasure. The story Greenamyer told afterward—after losing his priceless airplane and almost losing his life—was about walking across the lakebed of Edwards to a road, where he was overtaken by a concerned citizen in a truck. “An airplane just crashed and the pilot ejected. Did you see anything?” exclaimed the driver. “No,” replied Greenamyer. “I just got here myself.”

While he was working on the Red Baron, Greenamyer was also finding, retrieving, restoring, and selling vintage warbirds, including seven DHC-4 Caribous, the utilitarian transports that became vital as movers of U.S. troops and supplies during the Vietnam War. One of these was also vital to Greenamyer’s next audacious escapade: a 1995 attempt to retrieve the B-29 Kee Bird from a Greenland ice shelf, where it had crash landed in 1947 after its pilot became disoriented during a mission to the North Pole. The failed and costly effort to recover the bomber was the subject of a 1996 NOVA documentary.

Had the restoration succeeded, the proceeds would have funded Greenamyer’s new racer Shockwave. He designed it around a Pratt & Whitney 28-cylinder R-4360 engine, found wing panels from a Sea Fury and tail surfaces from an F-86 Sabre, and worked on its scratch-built fuselage. Meanwhile, he returned to the races and triumphed in a string of Reno championships with a carbon-fiber Lancair, stimulating the growth of the new Sport Class of air racing. Only a pilot of Greenamyer’s stature could have drawn competitors so quickly to a new class of racing. The year after his first Sport Class race, said collaborator Andy Chiavetta, “the whole Sport Class hangar was filled with airplanes.”

Last summer, when Greenamyer visited the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center to see his Bearcat Conquest 1 one last time, he was most interested in seeing the names of the “Pit Lizards” inscribed on the fuselage. I thought about that when Pete Law told me how much they all idolized him, how much he had poured into the airplane and how much they had all gotten, though they were all volunteers, from working with him on it. Greenamyer was controversial; plenty of posts in online pilot chat rooms call the Kee Bird debacle “shameful” and “unforgiveable.” But once you’ve scratch built an F-104 and flown it 1,000 mph to a speed record that 40 years later still stands, you can be forgiven, I think, for believing that anything is possible.

Somewhere in a hangar in California, pieces of Shockwave are waiting for an indomitable optimist with ambition as powerful as a Double Wasp engine and I guess a lot of dough. Maybe a team of racers and engineers could get that racer past 600 mph. They’ll also need the charisma of a Darryl Greenamyer, my favorite pilot.