Game-Day Traffic

Directing air traffic for Super Bowl XII in New Orleans, we controllers had to be on our game.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/26/c6/26c6f8d5-9f8e-4c74-bdc5-c32fc4546d82/17d_sep2015_moisanttower1977_live-web-resize.jpg)

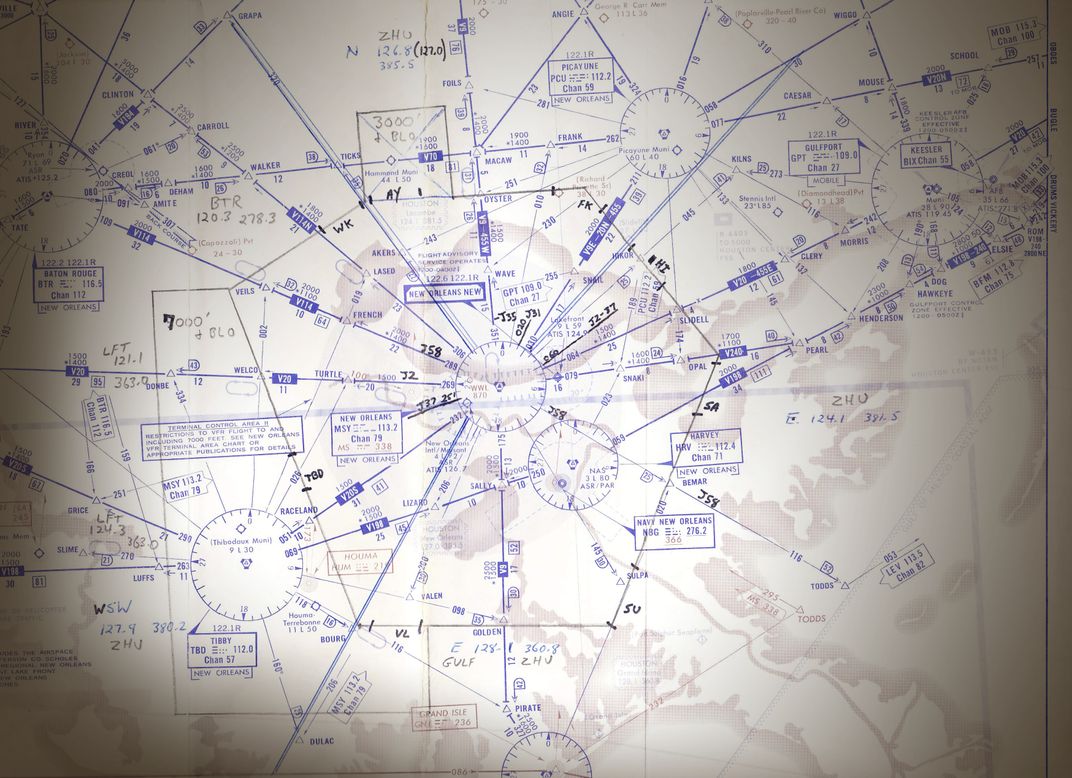

When the Louisiana Superdome hosted Super Bowl XII on January 15, 1978, many of the 75,000 fans in attendance traveled to New Orleans by airplane. Most of them had no idea they were part of another big game: the one in the air, with plays and tactics executed by air traffic control.

In the late 1970s New Orleans International Airport was popularly known as Moisant Field. Its air traffic control facility was Moisant tower, a 12-story building located in the middle of Concourse C. The ground floor housed New Orleans approach control, which managed the airspace within a (roughly) 35-mile radius of the airport. The top floor was crowned by the tower cab, the glass pentagon where controllers worked local airport traffic.

I reported for duty at Moisant in July 1977. My facility training manual proclaimed the tower “The Epitome of Service in the Science of Air Traffic Control.” It was a busy place with limited runways and complex airspace, catering to a mix of air carrier, general aviation, and military flights. Eugene “Thunder” Thornton, a grizzled veteran of air traffic control, told me on day one, “If you make it here, you can work traffic anywhere in the country.”

By December, I had completed on-the-job training in the tower cab and was certified to work all positions upstairs. The new year would bring more intense on-the-job training downstairs in approach control. The Sugar Bowl, the Super Bowl, and Mardi Gras were all scheduled for the same five-week period. That would mean a big boost in air traffic.

On Thursday, January 12, I was working arrival radar on the 2 p.m.-to-10 p.m. shift, with an instructor monitoring every radio transmission I made. Henry Boudreaux was an excellent instructor, a man of character and precision. He was typically patient and calm when working with new trainees. He was also a master of high-volume profanity when it came to ensuring the trainee never forgot his two basic rules. Number one: First come, first served. “I don’t care if that’s [expletive deleted] Air Force One out there!” he’d yell. “Number 5 [in the arrival sequence] is number 5!” The second rule: standard radar separation is three miles, no more. “TURN THAT 737 NOW OR YOU’RE GOING TO HAVE 6 MILES BETWEEN HIM AND CONTINENTAL!” I was learning a good air traffic controller is as much an artist as a scientist.

My training session ended at suppertime. As we debriefed the training period, the team supervisor spoke from the cloud of cigarette smoke that hung in the greenish darkness of the radar room: “Frey, after you eat, get upstairs and relieve local.” The local controller owned the runways, clearing airplanes to land and take off. Even though I was officially qualified to work upstairs, my journeyman colleagues constantly reminded me that, like a cast iron skillet, I needed plenty of seasoning. Nonetheless, I was looking forward to finishing my shift without someone looking over my shoulder.

**********

In the tower, I plug my headset into the local control console and look out at the fog that has enveloped the airport. As the temperature and dew point merge, the clouds thicken and drop to within a few hundred feet of the surface. The ILS (Instrument Landing System) approach to Runway 10 is in use. The glow of the approach lights, guiding pilots as they transition from instrument flight to visual flight, fades into the swamp to the west. High-intensity runway lights are on full bright, illuminating the runway like a Christmas tree. The tower cab is full of chatter. On the TV above my head, the radar image shows a steady stream of arrivals. The ground controller is lining up departures for Runway 1.

After a few minutes I’ve developed a mental picture of the airplanes for which I am now responsible.

“Braniff 133, turn right at the next intersection, contact ground 121.9.”

“Braniff 133, roger, good night.”

“Tower, Eastern 910 is ready on 1.”

“Eastern 910, wind 350 at 5, runway 1, cleared for takeoff.”

“Moisant tower, Southern 642 is with you on the ILS.”

“Southern 642, wind 340 at 6, runway 10, cleared to land.”

The weather is near landing minimums. If it gets any worse, arriving airplanes could end up diverting to an alternate airport. I work the usual assortment of aircraft, mostly DC-9s and 727s. There are not many “gnats” (general aviation airplanes) out flying on a night like this. Downstairs is spacing the arrivals nicely. No missed approaches despite the reduced visibility and low ceiling. Departures disappear into the murky sky right after they’re airborne.

The next to land is a Royale Airlines Beech 99. Visibility has come up to a couple miles, but the ceiling remains at just a few hundred feet. The Beechcraft is a mile from the runway, still in the clouds and slowing down. Four miles behind him is a Texas International DC-9. Texas 939 has reduced speed to 140 knots, but he’s still gaining on Royale. If this is going to work, it’s only because arrival gave me that extra mile of separation between the two airplanes. The Beechcraft touches down, rolls slowly to the midfield taxiway, turns right, and stops with 15 feet of its tail still obstructing the runway. The landing lights of the DC-9 pop out of the mist.

My decision is instantaneous: “Texas 939, go around!” “Fly runway heading, climb and maintain 2000, contact New Orleans approach on 118.1.” Before he can switch from my frequency to approach control, departure radar is on the interphone from downstairs: “Hey, stop all departures, we’ve got an emergency in progress.” The pilot of a Beech Baron is lost and disoriented.

The Texas DC-9, not expecting an encore, has climbed back into the darkness. Approach is immediately on the interphone to inform me that he really doesn’t need another airplane right now. I consider a reply but he has already hung up. We both issue new instructions to what seems to be a never-ending migration of airplanes.

Texas 939 is safely on the ground as downstairs vectors the last trickle of arrivals to the ILS. At Runway 1, a line of airplanes waits to take off. Up first is a Northwest Orient 747, a Super Bowl charter returning empty to Minneapolis. “What’s the reason for the delay?” asks the pilot. His voice says it’s been a long day in the cockpit. He’s watching the clock and the fuel gauges. As his airplane sits on the tarmac, crew duty time and gas are dwindling.

The Baron’s pilot is in luck: The team supervisor has moved Gene Barnett, a former airline pilot, to a spare radarscope, where he will work only one airplane, the Baron. Gene calmly guides the Baron down through the clouds and fog to a safe landing. After 30 minutes, the emergency is over. The word comes from below: “Launch those guys, it’s time to go home.” I watch the 747 begin its takeoff roll and tell the next guy in line, “Caution—wake turbulence behind the departing heavy jet, taxi into position and hold.” My relief is already issuing the takeoff clearance as I head downstairs.

**********

On Friday afternoon I finished my last shift of Super Bowl week. My training had to be halted, as people gathered around the arrival radar console to watch a performance the equal of any at the Superdome that weekend: Boudreaux, my instructor, was vectoring at least 20 airplanes to the ILS for Runway 1. A string of aircraft, spaced at three-mile intervals, stretched from Moisant to the Gulf of Mexico. Would I ever be able to do that?

I was due back to work Monday afternoon; my supervisor woke me at 2 a.m. “Come join the fun,” he said. Super Bowl XII was history, the parties were over, and everybody wanted to fly home…in the middle of the night. Twenty-four hours after the Dallas Cowboys defeated the Denver Broncos 27-10 for the Vince Lombardi Trophy, the game in the air ended.