Tales from an Aircraft Dispatcher

A simple spiral notebook brings back my father’s career with the airlines

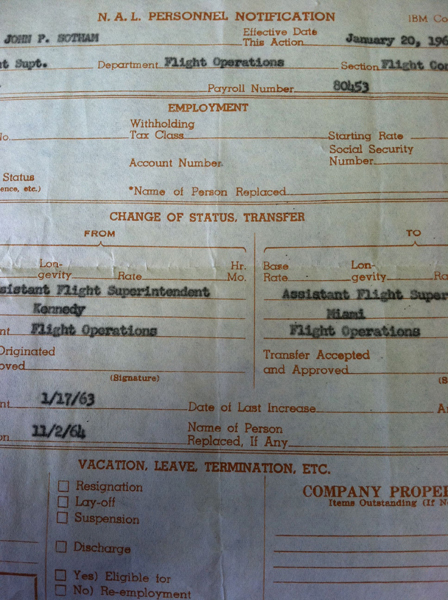

Recently, while cleaning out a house that belonged to my mother, I came across a yellowed piece of National Airlines (NAL) paperwork dated January 1965 that transferred John P.G. Sotham from New York’s John F. Kennedy airport, to Miami International, the airline’s corporate home. My dad, who died in 1998, started as a ticket agent, then attended the Sheffield School of Aeronautics on North 36th Street, the northern border of Miami International (MIA) that today features seedy hotels, a few ancient airline uniform shops, and the last true vestige of Pan American Airways—the Pan Am Flight Academy. In 1962, my dad was awarded the aeronautical rating of Aircraft Dispatcher.

Dispatchers compute fuel loads, and determine routes based on weather, and prepare flight plans based on maximum takeoff weights and field conditions. With the captain, they are jointly responsible for the release and safety of a given flight. The Sheffield School, and others, still train dispatchers—by the time my dad retired from Pan Am in 1982, he was guessing the job would be replaced by computers.

In 1965, my dad transferred from JFK to MIA—made official with a few keystrokes on a carbon paper form.

My dad did his computations long hand, until the day he showed me a brick-sized marvel that promised to make his work easier. Sadly, his Texas Instruments calculator, which cost him $50 (in the 1970s!), was itself soon dispatched by salad dressing leaked from a container in his work bag.

I was wondering what had become of the career, when I opened an inflight magazine last week and came across an article about U.S. Airway’s flight control office. The story profiled dispatcher Joe Mealie, and a photo of his work space—surrounded by flat-screen computer monitors displaying flights en route and real-time weather. The office was nothing like I remember when I visited my dad at work. His desk inside National’s scrubby concrete-block flight control building at MIA, with palm trees leaning at lazy angles outside, hung under a constant low ceiling of Pall Mall smoke, with banks of rotary phones and the constant clatter of teletype machines announcing runway closures or displaying smudgy renderings of weather fronts. Sweating inside the badly air conditioned building, he would deal with a DC-8 diverted because of a blizzard at Boston’s Logan International Airport, or perhaps assist the crew of a 727 circling over JFK. How far could they get with the gas on board? A pencil and paper would determine the answer.

I loved to hear him tell about the stories from his shift, including colorful tales of unruly passengers or medical emergencies that forced one of his flights to land, or the time an unfortunate stowaway climbed inside the wheel well of a 727 and didn’t live to see his destination. During the 1970s OPEC crisis, when jet fuel prices skyrocketed along with gasoline, he relayed wild rumors from other dispatchers that some airlines—looking to put the least amount of fuel possible on board—had a few jetliners shut down from fuel starvation while taxiing to the gate if they had run into an unexpected traffic delay. But, usually the tales featured weather. Always the weather. My mom and I learned to speak his shorthand about troughs aloft or dips in the jet stream. And we came to know airport codes almost as well as he did.

I barely saw him for weeks if he was pulling midnights. My parents exchanged notes to each other on a spiral notebook left on the kitchen counter. While cleaning, I unearthed one of the notebooks. A typical entry: “Hell of a night. PHI, JFK, EWR, all below minimums. Goddamn machinists about to go on strike again. Thanks for the tuna salad.”

It wasn’t until many years later that he confessed to me how stressful he found the job, and that on some nights, if there were particular flights that worried him, he’d sit in his car in the parking garage after the shift was over and wait until the jets—those he had released for push back in airports thousands of miles away on his watch but that were now the responsibility of his relief—had landed safely in the balmy night air of MIA. Only then would he return home and get some sleep.

There was none of that in the spiral notebooks, though. Just the day-to-day travails of a tough day at work.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sotham_photo.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sotham_photo.jpg)