Should the chief builder of the International Space Station be the company that offers taxi service there? Boeing thinks so.

Taxi to the Space Station.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Taxi-Space-Station-Boeing-631.jpg)

Alicia Evans grew up in Southern California dreaming of being an astronaut. The space bug bit her when she was five, she says, and has not let go some 30 years later. She recently submitted a second job application to NASA, joining some 6,300 would-be space voyagers vying for a maximum of 15 spots in the next astronaut class (eight were chosen). Asked whether she would volunteer for the first privately run human mission to Mars, the one whose crew (if it happens) will not return to Earth, she thinks for a moment. “I would consider it,” she replies.

Kavya Manyapu grew up in India also dreaming of becoming an astronaut. When she was three, she started watching space shuttle launches and dockings on TV with her father, an information technology specialist. When Kavya was 16 he moved the family to the United States to bring her closer to NASA’s front door. Since then, she has earned engineering degrees from Georgia Tech and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a “highly qualified” rating for her astronaut application.

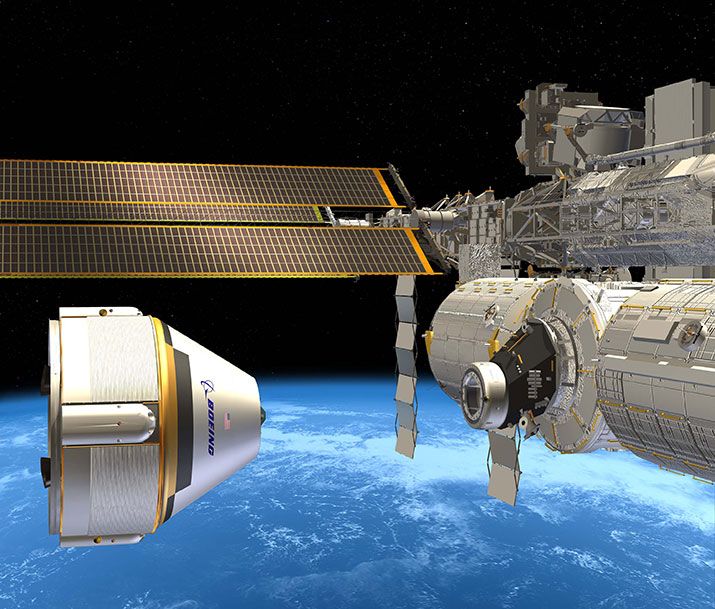

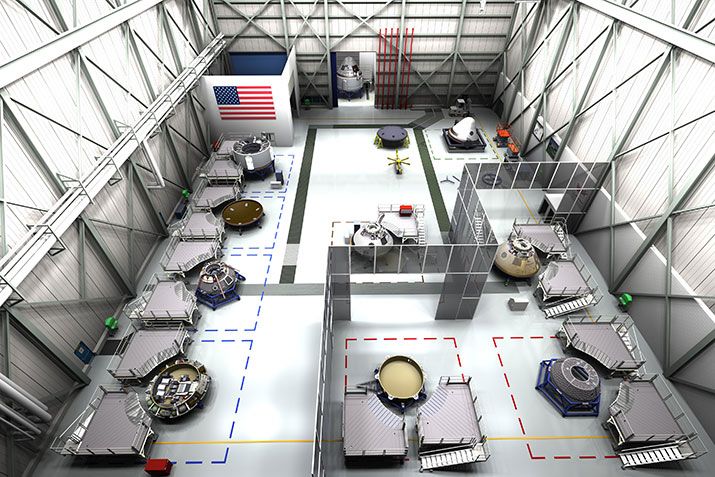

Today, the two young women work a few cubicles apart at Boeing Space and Defense Systems’ offices in Houston. They are among the 350-some employees designing the CST-100, the aerospace giant’s entrant in NASA’s competition for a privately built successor to the shuttle that will carry crews to the International Space Station on U.S.-built hardware, rather than the Russian Soyuz capsule NASA has been relying on since the shuttle retired. Evans is overseeing the environmental testing of a CST-100 prototype to be built next year, organizing the minutiae of a propulsion system test firing in New Mexico, and scheduling a heat exchange simulation in a vacuum chamber at Boeing’s huge test facility in El Segundo, California. Manyapu is a flight test engineer and a participant in the Mars Society research project to prepare humans for a trip to Mars.

There is absolutely nothing special about the CST-100 design center externally—several floors of featureless work stations in a faceless low-rise glass office complex on Houston’s southeastern outskirts. But Evans and Manyapu bring the invisible fire of their life’s ambition to work every day. It sits close beside them as they work methodically through the morning’s spreadsheets and emails. “Even if I don’t get to be an astronaut, I get to work for Boeing on a human spaceflight vehicle that a friend or colleague might fly on,” Evans reflects. “How awesome is that?”

Evans and Manyapu’s boss, CST-100 project manager John Mulholland, and the corporate hierarchy above him are counting on the young engineers’ passion to pull Boeing through a challenge it has not quite faced before. The company, as a visitor hears within five minutes of entering the building, has ample experience putting men and women into space. Boeing or companies that are now part of it, like McDonnell Douglas and Rockwell International, have been in the thick of every manned program from Mercury to the shuttle to the space station, for which Boeing is the prime contractor.

But all those programs ran according to the traditional script: cost-plus budgeting, in which every widget and layer of redundancy any administrator or relevant Congressman could think of was built in, the price being Uncle Sam’s problem. Boeing manager and former astronaut Chris Ferguson calculates that the shuttle cost taxpayers from $35 to $42 billion just in the design work leading up to its first flight. After commanding the last shuttle mission, in December 2011, Ferguson came to work for Mulholland as the CST‑100’s director of crew and mission operations—and informal guru to the space-struck junior staff. NASA’s successor human-flight program, Constellation, was scrapped in 2010 as unaffordable.

The price tag on the new Crew Space Transportation vehicle, as NASA has formally designated CST-100 and its competitors, will be “more than an order of magnitude cheaper,” Ferguson promises. So far NASA has paid about $600 million to Boeing to produce a CST-100 capsule, which is now approaching its “critical design review”—the rigorous series of test bangs, rattles, and blasts that Alicia Evans and others will conduct on the prototype before construction of the operational vehicle can begin. The company itself has co-invested an undisclosed sum.

Part of the projected savings comes from shrinking the size and scope of the vehicle. With a cone-like Crew Module fastened to its squat, cylindrical Service Module, the CST-100 is 16.5 feet tall and 15 feet in diameter. Its intended payload capacity is a mere 2,800 pounds, enough to carry seven astronauts and the equipment they need to survive a 24-hour journey to the space station. By contrast, the shuttle typically carried 50,000 pounds. In the future, most of that bulk will be toted by a separate commercial cargo vehicle.

More savings come, Mulholland and Ferguson say, from a different kind of relationship with NASA. If and when it is finished, the CST-100 will be Boeing’s property, not the government’s. The agency need not be the only customer for the new spaceship, though it is the only one in sight, save for the ultra-high-end tourism promoter Space Adventures. NASA has accordingly pared back its usual control-freakery, setting broad goals for what the new vehicle should do—get a crew to and from the station safely—and milestones to meet before each funding round. (There have been three so far.)

The new deal with NASA “increases the velocity of decision-making and the stability of decision-making,” says Mulholland. “Because all the systems are so integrated, if you change one element once the design is already set, it becomes very complicated.”

Ken Bowersox, another former shuttle commander who has consulted with both Boeing and its chief rival in the commercial taxi race, SpaceX, says that in traditional space projects, half the cost comes with the last few capabilities, which are usually added for reasons of safety. “We could never build a vehicle as simple as the Soyuz,” he says, “which is why we don’t have a vehicle at the moment.”

NASA may be ready for a new spaceship paradigm, but is Boeing? This is the overriding question Mulholland and his team will have to answer if the CST-100 is to survive to the maiden voyage with actual pilots. The aviation icon has to fight for the commercial crew vehicle contract, and for the moment, one competitor already has chalked up a victory in a different area. SpaceX has won the “commercial cargo” contest, and its unmanned Dragon spacecraft has been lugging equipment to the station regularly since October 2012. (Orbital Sciences also will ferry cargo there on its Cygnus spacecraft.) A third contestant, Sierra Nevada Space Systems, remains in the running for providing a commercial crew taxi with its Dream Chaser, though during the last round of funding, in July 2012, NASA awarded it less than half the money it gave Boeing and SpaceX (see “The Other Guys,” Aug. 2013).

In a nutshell, Boeing’s mission with the CST-100 is to produce a vehicle that is more reliable than the competition’s while matching SpaceX on cost and speed. And Boeing managers are confident they can do just that. Mulholland points out that Boeing has plenty of commercial market credentials. He finds it “almost incredible that people would doubt the capability of a company that is the largest U.S. exporter [of commercial products].”

Mulholland acknowledges that while the new capsule is somewhat different from what the company has done before, Boeing has vast experience in getting people to space and back. He flaunts the cell of hardcore space enthusiasts he has recruited from within the vast Boeing corporate structure. “We have been very successful in getting a young cadre here that is just relentless,” he says. “I’m glad I don’t have to compete with them.”

Mulholland, a crisply organized technocrat whose taut, engineered sentences contrast with his relaxed business-casual dress, has a résumé that is as space-establishment as they come. He joined NASA right after getting his engineering master’s at New Mexico State University in 1986, and worked his way up over 16 years to become deputy operations manager for the shuttle. He jumped to Boeing in 2002, and from 2008 to 2011 rose to be program manager for its shuttle effort. (Boeing absorbed Rockwell in 1996, inheriting the latter company’s contract to build the shuttle.)

But Mulholland doffs the corporate mask with relish to play space-nut-in-chief. At the end of an interview that dwells on the intricacies of systems integration and performance parameters, he jokes: “Humans are going to need another place to live eventually. Single-planet species don’t survive. Just ask the dinosaurs.”

On the other hand, Mulholland stresses that “our focus has been on bringing in mature but innovative approaches,” “mature” meaning those that have been proven over years of manned missions. Mulholland’s response to SpaceX’s latest successes is subtle. “The wonderful thing about cargo is that you can learn as you go,” he says. “If you have an accident, you have lost a lot of money but not crew.” Part of Boeing’s long experience in spaceflight includes, as a partner in United Space Alliance, a return to flight after the loss of a crew.

Ferguson, who does not mind combining his primary job as crew chief with a side job as attack dog, is more to the point. “Manned spaceflight is an unforgiving business, and SpaceX might build up the credibility for it in a dozen years or so,” the former shuttlenaut says. SpaceX founder Elon Musk “is a great guy who has done some fantastic things, but the time for self-congratulation is after everyone is back safe on the ground.”

In the tight-knit space industry, several members feel confident that Mulholland could lead his company to snatch the commercial crew prize. One, James Muncy, a D.C.-based enthusiast who heads both the Space Frontier Foundation and the Polispace Consultancy, says: “SpaceX is like Boeing was under Bill Boeing 90 years ago. But you are seeing a culture inside the CST‑100 that is very different from the rest of Boeing. The fact that Boeing has its own money at stake makes it very different than a cost-plus contract.”

More support comes from Space Adventures, the highly entrepreneurial company best known for sending multi-millionaires for a holiday on the space station via Russia. Space Adventures might seem like a natural fit with SpaceX, but it partnered with the CST-100 program instead when the commercial crew quest was just getting started in 2010. “Boeing has a tremendous space heritage and the CST-100 is a fantastic system,” says company president Tom Shelley.

He does not promise that a ride aboard the CST-100 will be cheaper than the current Soyuz ticket, which costs about $70 million per seat. But the training time would be slashed from four months to two, Shelley says, in part because space tourists will no longer need to learn Russian or train in Russia. “That’s a huge factor for our clients,” he says.

But the surest sign that Boeing means business with its commercial crew efforts comes from NASA itself. In the agency’s most recent financing round, announced in August 2012, the CST-100 topped all recipients with $460 million. SpaceX’s Dragon was close behind with $440 million, while Sierra Nevada received $212.5 million—setting up a two-horse race with a third contender still on the track in case one of the leaders breaks a leg.

Boeing anticipates training and providing a crew of two for the initial Crewed Flight Test, which could occur as early as 2016. (SpaceX also will train its crew, but hasn’t decided whether they will be NASA or SpaceX astronauts.) NASA may choose to participate in the mission, so the crew may be a mix of Boeing and NASA astronauts. The first crew services flight to the station will be made in late 2017, and the crew likely will be NASA astronauts trained by Boeing. I ask Ferguson how he feels about flying the CST-100. “I think it would be really cool to be the first non-government astronaut” in orbit, he says.

Boeing’s space (and military) heritage brings plenty to bear on the consumer crew contest, both Mulholland and Ferguson say. The company is thick with engineers who know intimately how to “design out all that stuff we always complained about,” in Ferguson’s words. That would include, for instance, the 1,100 switches in NASA’s over-designed shuttle that bedeviled astronauts for three decades.

But institutional memory both before and beyond the shuttle is at work in Houston today. Mulholland and his team metaphorically rummaged through Boeing’s immense technology closets to dust off pieces of hardware that otherwise might not fly another day to put aboard the CST-100. Mulholland says that the new vessel will use flight computers originally designed for the unmanned X-37B spaceplane, which Boeing built for the Air Force in the latter half of the last decade (see “Space Shuttle Jr.,” Dec. 2009/Jan. 2010). The propulsion system for the capsule was scavenged from ground-based missile defense technology. The base heat shield that will protect Boeing’s astronauts on reentry is an update of one used in Apollo. The CST-100’s interior lighting is copied from the 787 Dreamliner commercial jet. And so on.

Mulholland spins even Boeing’s famous problems with the Dreamliner’s lithium-ion batteries as a plus for CST-100 development (the capsule will use a different type of lithium-ion battery). Boeing space engineers crossed divisional lines to consult with civil aviation colleagues on the battery conundrum, and brought back valuable insight on how to prevent similar snafus with the commercial crew vehicle. “You learn as much from those kind of situations as you do from clean-sheet engineering,” he says. “A number of the improvements Boeing made have already been incorporated into our system.”

Nearly as important as Boeing’s in-house experience, its managers say, are the relationships the company has built up with suppliers and collaborators—other pillars of the aerospace industrial establishment—over the years. The computer system that will pass from the X-37B to the CST-100, for instance, was built by defense giant General Dynamics. The propulsion system borrowed from missile defense originated with Pratt & Whitney.

For the CST-100 program, the critical third-party relationship is with United Launch Alliance, whose Atlas V rocket will lift the crew capsule clear of Earth’s atmosphere. Or one should say not-quite-third-party relationship. ULA itself is a joint venture formed in 2005 between Boeing and its arch-rival in defense contracting, Lockheed Martin. CST-100ers view it as an external partner, though. “One of the factors that makes this project about the hardest thing in the world is bringing together three big organizations: Boeing, ULA, and NASA,” Ferguson says. “NASA is very interested in how we are going to work with ULA.”

The trade-off for the complication of teaming with ULA is that the Atlas V boasts a long and nearly flawless track record, some 40 successful satellite launches since 2002. (Before ULA’s formation, Lockheed operated it solo.) That gives Boeing execs one more talking point for their argument that their hands are safer than SpaceX’s, which, true to maverick form, is launching its commercial crew entry on its own Falcon 9 rocket. The Falcon 9 has been through five launches, all successful. Ferguson says that it might take a dozen launches to “start to establish some credibility.”

In all its storied history, one thing Boeing has never done is actually operate a spaceflight—training astronauts and running mission control. In the past, contractors would deliver the hardware and NASA would handle the flights. If Boeing wins the commercial crew derby, it will take over that job. That’s where Chris Ferguson comes in.

Ferguson, now 52, adds a dash of bona fide astronaut stuff to a project otherwise dominated by gearheads and bean counters. After studying engineering at Drexel University and the Naval Postgraduate School, he spent 12 years as a Topgun and test pilot, landing Grumman F-14 Tomcats on aircraft carriers in the Mediterranean. He resigned from the Navy to join NASA in 1998, and made the first of his three shuttle flights aboard Atlantis in 2006. He makes no bones about being a reluctant recruit to the corporate sector, or his disappointment in watching a confederacy of bureaucratic and political dunces (as ex-astronauts tend to see it) kill off the Constellation program. “I liked my old job better,” he says, “but my old job doesn’t exist anymore.”

Now he energetically carries the CST-100 flag and pushes the company’s engineers to plan for commercial spaceflight from a pilot’s perspective. For instance, until he came on board, no one had thought very much about flight simulators. “Simulation is the lifeblood of the astronaut,” Ferguson says. “If you want to test a new airplane, you take it out and fly it. You can’t do that with space.”

With the imagineering phase of design finished and a test flight not likely until 2015, this is a particularly hard time to maintain enthusiasm in the chancy multi-year project. But space engineers, like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s rich, are different from the rest of us. They understand that humankind’s ascent to the stars is a long march, and they are content to be humble soldiers in that effort. At least that is what they like to say. Everyone at CST HQ seems to agree that the chance to contribute to a brand-new flight system, one that will carry real astronauts no less, is akin to a divine gift. “In a way, it’s a shame that NASA had to abandon Constellation and its own program,” Mulholland says. “But that’s made it such an exciting time for people to get into aerospace.”

Though Alicia Evans has not launched for Mars yet, late last year she did quit her native southern California for Houston. She spent most of her previous 11 years with Boeing at El Segundo, a stone’s throw from the beach (and not far from SpaceX’s headquarters, in Hawthorne). There may be yet another move next July, when the CST-100 program relocates to Cape Canaveral, Florida. But “the opportunity to work on a crewed vehicle was too good to pass up,” she explains. “El Segundo does not have the passion we have here.”

That is just what Boeing wants to hear.

Craig Mellow is a freelance journalist in Staten Island, New York.