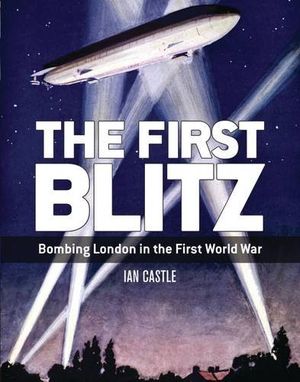

Terror Over London

A new book recalls the city’s first blitz during World War I.

:focal(547x207:548x208)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/be/fc/befc39b0-0a54-48cb-9afd-96f4eb918fe9/zeppelin_part.jpg)

Ian Castle’s book, The First Blitz: Bombing London in the First World War, chronicles the German siege of the city by airships and Gotha bombers during the war, using Londoners’ eyewitness reports. “I had lived in London all my life, and realized this was a period of the city’s history of which I knew very little,” says the author. “I started researching the air raids and discovered a trove of information held in documents stored at the National Archives in London. From that moment, the idea of the book was born.” Castle spoke with Senior Associate Editor Diane Tedeschi.

Air & Space: Was the effect of the bombing raids on London more of a psychological threat than a destructive force?

Castle: The bombing raids on London had a dual purpose. London became the ultimate target as it was the seat of government and hub of the British Empire. It therefore made sense to strike at its docks and industrial targets. But at the same time, Germany believed if it could set fire to large areas of the city, the morale of the civilian population would collapse, and they would demand that their government sue for peace.

Did the Germans have any misgivings about hitting London’s civilian population?

Initially, Kaiser Wilhelm II refused to sanction any air raids on Britain, because of his close ties with the royal family, and—believing like many that the war would soon be over—he did not want to be held responsible for the destruction of the capital’s historic heritage. Even after finally authorizing attacks on England in January 1915, he held London out of bounds until May of that year. Then, when Germany did attack London, any pretense that raiding zeppelins—or bombers later in the war—were aiming at specific targets evaporated. Having avoided British defenses, the raiders aimed to drop their bombs as quickly as possible over the sprawl of London and then head for home.

What kind of technology, if any, did Britain have for detecting the incoming zeppelin bombers?

During the period of the zeppelin raids, specialized technology to detect their approach was limited. Britain soon learnt, however, that zeppelins transmitted a standard radio message when setting out on a raid. So after they knew when to expect a raid, it then became a case of discovering where the zeppelins would come inland. First indication of a line of approach often came from British ships dotted around the coast, which were connected to the mainland by telephone. Inland observer posts covered the main approaches to likely targets—also able to telephone information into a central point. As the war progressed, experiments were made with acoustic mirrors—large concrete structures or concave bowls cut into cliffs— with a microphone attached that could help a trained operator pick up the engine noise of approaching aircraft at extended distances. Interestingly, a few of these structures from World War I still survive on the British coast.

What kind of defense did the Royal Flying Corps mount against the incoming zeppelins?

The aircraft sent up to oppose the zeppelins had a difficult job. Although a zeppelin is a massive object, they didn’t attack in daylight, only at night around the period of the new moon when skies were darkest. This made it difficult for British pilots to spot them, and noise from the pilot’s own engine meant they couldn’t hear them. The work of the searchlight crews became of vital importance. Assigned set patrol lines, pilots monotonously flew backward and forward until a searchlight illuminated a raiding zeppelin. Once lit, the pilot left his patrol line and made direct for zeppelin, hoping to reach it before the searchlights lost contact or the raider disappeared into clouds.

In what ways were the zeppelins vulnerable?

Well, a 650-feet long container holding about two million cubic feet of highly inflammable hydrogen certainly has a unique vulnerability, but one that initially proved surprisingly difficult to exploit. Early in the war, the British convinced themselves that the Germans were cunningly using an inert gas to surround the hydrogen cells, which prevented their early incendiary bullets from working—only later was it recognized that the bullets weren’t fit for purpose. And ordinary lead bullets couldn’t ignite the hydrogen, the only caused a limited loss of gas. So until the summer of 1916, the recommended method of attacking a zeppelin remained bombing them, but a zeppelin could out-climb the aircraft sent up against them. But when the British developed three bullets with a mixture of incendiary and explosive attributes, the results were spectacular. Those bullets were a real game-changer.

In 1917, the focus of air raids on London switched from zeppelins to the Gotha bomber. What brought about that change?

The introduction of the new incendiary and explosive bullets in the late summer of 1916 meant Britain now had an effective weapon to exploit the zeppelin’s vulnerability. On September 3, 1916, a British pilot shot down SL.11, the first German airship brought down on British soil. Within a month, two more followed, with another brought down by anti-aircraft fire. Both the German Army and Navy operated fleets of airships, but this first loss, of an Army airship, brought about a rethink. The German Army, never as enthusiastic about airships as the Navy, decided to end it there and switched their focus to attacking London with the new Gotha bombers. The Navy persisted with their airships but generally avoided London’s strengthened defenses.

Were there any friendly fire incidents, in which British air defenses shot down their own aircraft?

The use of anti-aircraft guns in the first half of the war remained unsophisticated, leading to instances where guns opened fire on any passing aircraft, not bothering to check whether British or German. This friendly fire caused damage but did not result in loss of life. As the number of anti-aircraft guns increased later in the war, when London came under attack from the Gotha bombers, new methods were introduced to reduce this problem. The commander of London’s defenses created zones around the capital exclusively for either guns or aircraft. This meant that if an aircraft flew over a gun-only zone it was hostile. Friendly fire also affected civilians. Many were injured and some killed by falling anti-aircraft shells.

Did Britain learn anything from these attacks that enabled it to better defend itself during World War II?

By 1918, a highly sophisticated aerial defense system had evolved. The system proved extremely effective, and later formed the basis of Britain’s aerial defense—with the addition of radar—when German aircraft returned to the skies over London in 1940.