Thanks For the Memories

Air crews recall their service as roadies for Bob Hope’s USO show.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/07A_DJ10-flash.jpg)

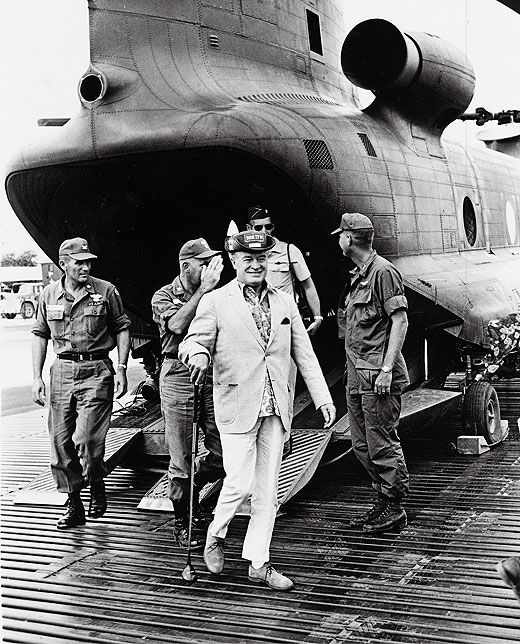

He starred in the Ziegfeld Follies with Fanny Brice and Josephine Baker in the 1930s, traveled the Vaudeville circuit as one half of a dancing team, and made more than 60 movies, including seven Road pictures with his pal Bing Crosby. But what most people remember about Bob Hope is that he entertained U.S. troops with annual USO tours in war zones all over the world.

"Along about September each year," Hope wrote in his 1966 memoir, Five Women I Love, "that tingle in the air is not the first sign of autumn in the San Fernando Valley. It's the annual stirring among my staff concerning where the Defense Department is sending us this year. Each summer the Joint Chiefs of Staff gather with the U.S.O. and commiserate, ‘He got back okay last Christmas…okay, let's try harder.' Then they drop little pieces of paper listing all the world's trouble spots into a hat, and humming choruses from Macbeth they stir gently."

Hope performed his first radio show for servicemen in March 1941 at an Army Air Corps base at March Field in Riverside, California, and for the next 50 years he took his show to some of the world's most dangerous places. He ducked air raids in Italy and Algeria during World War II. During a 1964 visit to Saigon, a Viet Cong truck bomb intended for Hope exploded 10 minutes before his troupe arrived at their hotel. "A funny thing happened as we arrived in Saigon," Hope later joked to the troops. "I met my hotel going the other way."

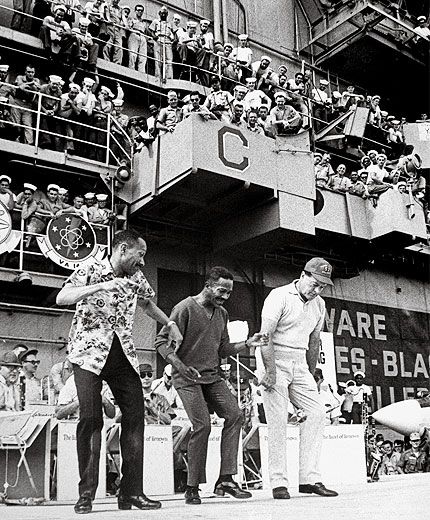

When he wasn't visiting bases or aircraft carriers, he was entertaining the war-wounded in hospitals. Over the years, under the auspices of the United Service Organizations, Hope reached hundreds of thousands.

But his trips required extensive planning, and they couldn't have been carried out without the help of pilots and navigators, wing duty officers and mechanics, crew chiefs, and many others. Here are a few of their stories.

Alaska, 1942

Retired Air Force Colonel Robert Gates flew Hope to Alaska and the Aleutians for the first-ever USO show. He also flew Hope to shows in Europe after World War II, and to Vietnam in the 1960s. Gates spent more than 30 years in the Army Air Forces and Air Force, serving in Europe during World War II as a troop transport pilot for the 101st and 82nd Airborne. In 1985, Gates and Hope helped establish the Bob Hope Village, a retirement community in Shalimar, Florida.

In 1942, we went down and checked out in the admiral's airplane—a Lockheed Lodestar C-60—in Kodiak, Alaska. And the general said to me, "You've got to go and pick up the admiral's airplane and go up to Fairbanks and pick up a USO show."

I said, "What's a USO show?"

He said, "We don't quite know, but we think it's a bunch of entertainers, and they have top priority, so take good care of them."

So we arrived at Fairbanks and we walked into the Officers' Club, and lo and behold, there was Bob Hope with Frances Langford, and Jerry Colona, and Tony Romano the guitar player, and an Army captain. And I introduced myself, and Bob says, "You're gonna fly us?"

I said, "Yes, sir."

And he said, "How old are you?"

I said, "I'm 22."

And he said, "You still got growing pains!"

And that was my nickname until about two months before he died [in 2003]. That was my nickname through 60-some years.

Nobody flew at night [in Alaska] because there were no radio letdowns [and navigational beacons] to speak of, except at Fairbanks and Anchorage, and at Elmendorf [Air Force Base]. So we went over to Valdez, the main port for Alaska.

Bob did a show at about three in the afternoon for about half of the 600 or so servicemen who were there unloading the ships. And we were just ready to leave when the commander said, "Mr. Hope, only half of my troops got to see your show. Couldn't you do another one now?"

And Bob says, "Of course we can!"

And I said, "Bob, no we can't. We can't fly at night up here. We can't go back tonight."

"Oh, sure we can," he says. "It's only an hour and a half over there. We can do that."

So we did the show, and got back to the airport at about 9 p.m., and it's raining. And the mountains are 12,000 feet high there. So we did a tight turn at 12,000 feet through the rain and started on course, and we got into the ice and one engine quit. And then the radio went out. So there we were, the mountains higher than we were, losing altitude about 200 feet a minute, and how we got through is beyond me to tell you, other than God was looking out for us.

I remember Bob coming up and tapping me on the shoulder and saying, "Everybody back there is praying."

I said, "You tell 'em don't stop!"

The commander of the 11th Air Force had sense enough when they couldn't contact us to turn on all the search lights, and point them to this same point in the sky over Elmendorf. And on our arrival, as we were letting down at about 6,000 feet, we saw the glow in the murk in the sky, and let down on that and landed.

We couldn't taxi, we were all iced up, and had only one engine. So all the generals come rushing out of there, and the base commander and so on, and they were thanking Bob for a safe trip and everything, and I was the last one to come out of the airplane. And Bob put his arm around me and said, "Okay, now let's go to the barracks and change our drawers." And that's how we became the best of friends.

When I met him, at age 22, it changed my whole life.

Far East, 1962

James Mock was a member of the California Air National Guard in 1962 when he was asked to fly Hope and his troupe to various U.S. military bases in Asia. His military flying career had started in the Missouri Air National Guard, where he flew B-25s, B-26s, and RF-84Fs.

After leaving the military, Mock spent 37 years with TWA, retiring as a 747 captain. In 1995, he purchased the Caravelle Theater in Branson, Missouri. Bob Hope would perform his last live stage show at the Caravelle later that year.

I went to TWA in 1953 and flew Martin 202s and 404s, and DC-3s, and then I took military leave and went into the Air Force. I thought you had to be an Air Force pilot—or Navy, or Marine—to make your mark in the world.

When [the Department of Defense] needed someone to fly Bob Hope [in 1962], I was just off active duty Air Force for the Berlin Wall crisis, was a flight commander, a Boeing C-97 instructor, and I knew the routes, so they asked me to do it.

We started from Van Nuys [airport] and went to Japan, and started flying all through the Air Force bases in Japan, Korea, Taiwan and the Philippines.

We were flying a C-97 [Boeing Stratocruiser]. That airplane is built on the same chassis, you might say, as a B-50 or a B-29, but with bigger engines, so it has a huge cargo bay. The plane was a little bit VIP, but the main thing is that we had the cargo bays stacked with mattresses so Bob could crawl in there for the long, long flights. He'd come out and he'd smile and say, "Well, I'll just slap my wrinkle cream on and we'll be ready to go."

It was an unbelievably complicated airplane. They had the biggest engine we had ever built at that time; it was the same engine [a Pratt & Whitney R-4360] that was on the [Convair] B-36. The Air Force told us: "You'll never finish the trip." The C-97 has 28 cylinders, four rows of seven cylinders, and 56 spark plugs per engine, every one wanting to go wrong.

Well, we made up our mind we had to do it, so we took engines that were neither new engines nor old engines, they were right in between—they were kind of proven a little bit. We kept them running, and the trip worked out.

At Subic Bay [in the Philippines] Bob did a show on the flight deck of the Kitty Hawk. Well, when we got to Cubi Point, that's a small base with small airplanes. They didn't have a tug big enough to move that big C-97, so we had to reverse it. You could reverse for 30 seconds, and then you had to stop so you didn't bake the ignition harnesses. Then you had to stop yourself with your forward thrust, and you were very, very careful that you didn't tip it over on its tail. It was a little tricky, but we backed it in to where if you've got the right camera angle, it looks like the airplane was sitting on top of the carrier deck.

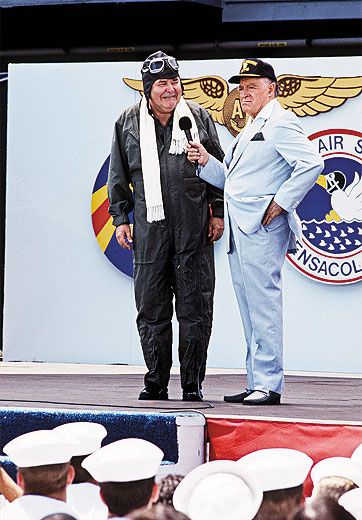

I loved to watch Bob. I couldn't get enough of his shows. The magic came in the effect it had on the audience.

Bob gave his very last live show here at our theater, the Caravelle. His daughter, Linda, says, "Jim, you've got to stick with Pops because he can't see, and he'll walk right off [the stage] and break his neck." I was trying to stay right with him, but he was kind of fidgety, you know, and he said, "Now Jim, don't worry about me. Just tell me: Is that Anita [Bryant] out there?" And I said, "Yes, Bob, that's Anita." And he said, "You just stand back and watch my smoke." He walked right to her, and that's when they did their wonderful last show.

South Vietnam, 1964

Thomas Anderson was a 34-year-old major commanding the 62nd Aviation Company "Outlaws" at the time of Hope's 1964 Christmas show in Vinh Long, South Vietnam. After the Vietnam War, he worked at the Pentagon, retiring from the Army Materiel Command in 1976. Today he helps manage the Vinh Long Outlaws Association.

On December 17, 1964, the 13th Battalion headquarters notified me that Bob Hope was coming to Vinh Long Army airfield on Christmas Day. The show was initially scheduled to be held in Can Tho, headquarters of the 13th Aviation Battalion, but the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel J.Y. Hammack, recommended that the show be held in Vinh Long, partially because it was rather isolated in the rice paddies of the Delta and could be better secured.

We were thrilled. I had to keep it fairly quiet because of the sensitivity of the visit, but I did bring into the security arrangements my executive officer, Captain Al Iller, and of course Major George Derrick—both of us commanded UH-1 "Huey" helicopter companies there at Vinh Long.

What made for some high anxiety was that on Christmas Eve we were deployed on a combat assault mission north of Saigon, near the Cambodian border. I was afraid that we wouldn't get back in time for the show. It turned out to be one of the largest helicopter airlifts up to that time in the conflict. About 165 helicopters from seven companies were involved—the helicopters formed a miles-long column in the sky. After a 50-minute flight, still in formation columns, the aircraft made their initial assault landings in two pre-designated landing zones near the Cambodian border. Additional ARVN [Army of the Republic of Vietnam] troops were then picked up at nearby staging areas and several more assault landings were made. By this time, all aircraft were running low on fuel.

Because the operational area was so remote, regular fuel trucks couldn't be used. Instead, we had to refuel from 55-gallon drums in the staging area. It took about three to four hours to get all these helicopters refueled because they had a hand pump on each one of these drums. The aircrews were first told at the refueling point that Bob Hope would be performing at Vinh Long at 1300 hours that day.

I had plenty of time because I had determined that I would be the last one to leave, to make sure that everybody else got off. We decided to strap red- and green-color-smoke grenades to the skids of the helicopters. We were the last two ships to get back to Vinh Long, arriving just after Bob Hope's C-123 landed. The crew chiefs pulled the cords and popped the pins on the smoke grenades and did about two circle passes over the top of Hope and the group.

After we landed, Hope said, "Do you have a place where I can sit down for a couple of minutes?" I took him to my quarters, and while we were sitting there chatting, he said, "You know, I usually have a golf club with me. You wouldn't have a golf club handy, would you?"

I said, "No, we've had to close the Vinh Long Country Club for the duration."

Bob Hope made eight more trips to Vietnam in later years, sometimes playing to as many as 12,000 troops. But I'm sure no performance could be more memorable than that Christmas Day show in a dusty little Mekong Delta airfield before 400 troops in the Vinh Long compound.

Gulf of Tonkin, 1966

When Hope visited the USS Bennington in 1966, Captain Richard Graffy was the carrier's commanding officer. He retired from the Navy in 1969 and spent a number of years building houses and doing blue-water sailing here and there, including the turbulent South China Sea. He now lives in Virginia.

While transiting from our home port of Long Beach, California, to the Gulf of Tonkin in the late summer of 1966, the ship received a message from Pacific Fleet headquarters requesting whether the Bennington would be interested in staging the Bob Hope Christmas show for that year.

I'm not sure why the Bennington was chosen rather than one of the two other carriers in Tonkin Gulf at the time. I can only surmise that since we operated on a three-and-a-half-hour cycle (for launch and recovery of aircraft), as opposed to the other carriers' one-and-a-half- to two-hour cycles, that may have played a part. The show had to be staged on the flight deck and conducted between air ops cycles since the audience of several thousand spectators would be on the flight deck.

Prior to arriving on the Bennington, the Hope show entertained some groups of soldiers and Marines ashore in Vietnam. The Les Brown Band had instruments, and all the cast had personal luggage well beyond the capacity of the Bennington's helicopters to transport. Instead, the show was airlifted by means of either Army or Marine transport helicopters from Da Nang. They had insufficient range to reach the carrier in its assigned operating area at Yankee Station [the location for aircraft carrier operations], so it became necessary to improvise.

Following an aircraft launch and recovery around noon, the ship steamed west at flank speed to intercept the helicopters that had launched from Da Nang. After unloading and refueling, the helicopters headed back, while the ship returned at flank speed to its operating area in time to launch a new flight and recover the previously launched aircraft. I doubt if any fighter aircraft escorts were used, since it was rather well established that the U.S. Navy pretty much "owned" the Tonkin Gulf below the 17th parallel.

The usual scheduled flight ops were conducted immediately before and after the show.

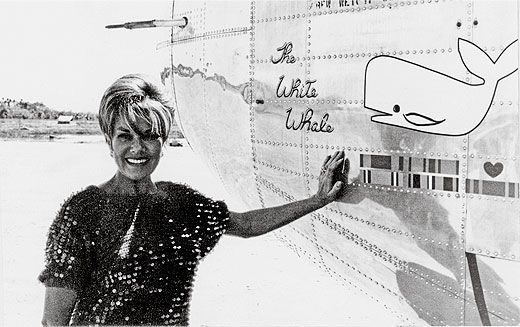

[After the show,] Phyllis Diller was invited to the bridge of the ship to view nighttime aircraft catapult and recovery operations. She asked about the array of telephone handsets surrounding the captain's chair on the bridge that connected directly to some of the more important stations on the ship. She singled out the one that connected to the captain's plot where the surface navigation was maintained, and was manned 24/7. It was suggested that she call and ask for the correct time, which she did. She was told it was 22:45:52, to which she replied, "Dammit son, I asked for the time, not my physical measurements!," followed by her signature cackling laugh.

Diego Garcia, 1972

Ronald Ronning was a 19-year-old Seabee electrician third class on the Navy communication station at Diego Garcia in 1972 and 1973. After returning to the States, Ronning went into the Army as a combat engineer, eventually training National Guardsmen. He is now mayor of Appleton, Minnesota.

They had draft numbers in those days, and my father called me one day and said, "You've got number 7." I said, "Are you sure it isn't 277?" So I said, I'm going to join the Seabees because I'm an electrician. I went to the recruiter, and he said, "You don't want to go into the Seabees, you'll end up on this little island in the Indian Ocean, that little island right there," and he points to it on a map. I said, "No, of all the places in the world, I'll never go there." So where's my first tour? Diego Garcia.

I think it was 115 degrees every day, and humid. I was an electrician there, lighting the runway. We had an airstrip, but it was 4,000 feet long and was for C-130 cargo transports.

We wanted Bob Hope to come to Diego Garcia. And we needed 2,000 extra feet on the runway—a total of 6,000 feet was needed for a C-141 jet. We worked 24 hours a day for two or three weeks. A thousand Seabees were on that island and they hadn't seen a girl for six months. So that was our incentive. Bob Hope's jet was the first to land on Diego Garcia.

We had regular runway lights, portable, which had rubber cables running all along the side of the runway. We'd plug them in, and the runway strip would be red at one end and blue on the other. There were nights when we couldn't get the lights on. You'd throw the switch and nothing would come on.

It was like a sea of red crabs on the runway all the time, like a swarm. They would pull apart the lights on the runway and the planes couldn't see to land, and we weren't within 1,000 miles of anything—you couldn't land anywhere else. The planes would be ready to run out of fuel in the air.

Many nights they would tell us the lights were out. I don't know if you've ever watched the movie Hatari! with John Wayne, where he [hunts rhinos] from a little chair mounted on the hood of a truck. We had a chair on our truck, and I would sit in it, and we used to tear down that runway at 50 miles an hour, trying to find the break in the cable lines so the planes could land.

The Bob Hope show was probably the highlight of my tour. I got to sit in the front-row seat because the runway crews worked all night keeping the crabs off the runway.

Spain, 1987

The 57th Military Airlift Squadron at Altus Air Force Base in Oklahoma transported Hope and his troupe in 1987, and Major Philip "Hawkeye" Pierce was the third pilot on the crew. Today, Lieutenant Colonel Pierce is director of operations of the 89th Airlift Squadron, 445th Airlift Wing, at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

We generally supported all the USO tours with [Military Airlift Command] airplanes, so it was appropriate for us to step up and fly Mr. Hope around the world for that particular mission.

We had two [C-141] aircraft. Both airplanes functioned perfectly.

The big hiccup was trying to get into the Azores, into Lages. We couldn't land there. There were 50-knot winds, but they weren't just 50-knot winds, they were actually crosswinds. At the time, we could only go up to a 25-knot crosswind [in the C-141]. So we were really getting buffeted. We were able to loiter overhead long enough for Mr. Hope to talk to the folks down there via the radio.

Due to the incredibly bad weather, we had to divert to Rota Naval Air Station in Spain, where we put on an impromptu show. We showed up unexpectedly, but boy, did they ever pack the theater at midnight. When the word spread that Bob Hope was showing up, people came out of the woodwork. And that was the last show.

Berlin, 1990

Bob McDaniel, a 39-year-old lieutenant colonel and a C-141 flight examiner pilot at Charleston Air Force Base in South Carolina, learned in 1990 that Charleston would crew a USO tour to Germany. McDaniel is now the director of St. Louis Downtown Airport.

I was in the right place at the right time. When the USO tour came up, it fell to Charleston to man the mission, and since this was a special USO tour that would be going to Berlin, they had to have a crew that had the Berlin corridor qualification and a Russian visa. It turned out there were only two of us that had those qualifications. So that's how I got on the crew.

We had a double crew, with four pilots, four flight engineers, two loadmasters, and two navigators on board, and we switched off on the various legs.

We were told that this would be [Bob Hope's] last USO tour. We celebrated his 87th birthday on board the aircraft on the flight. Of course [Operation] Desert Shield rolled around and Mr. Hope made one additional trip in December 1990, but it was very low key. It wasn't the multi-location tour that he had done in the past.

At the Berlin Wall, the East German guards were still standing at some of the old guard posts, and Mr. Hope started a conversation back and forth through a couple of holes in the wall. They exchanged hats, and took photos of Mr. Hope wearing an East Berlin guard's hat. It was very impromptu, and you could tell Mr. Hope was really enjoying it. I remember it was probably in the low 80s that day, the sun was shining brightly, and it was warm enough that just walking around you'd work up a sweat. Mr. Hope had his jacket on, collar turned up—you could tell he was on the chilly side, just like any other old geezer.

Mrs. Hope looked out for him quite a bit; she could tell when he was tiring, and she would take him away and get him the rest he needed. But when it was showtime, he was always 100 percent.

Rebecca Maksel is an associate editor at Air & Space/Smithsonian.