That Old Crate

From Minnesota cratemakers, a new CG-4 glider like the ones they built in World War II.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/JJ11-That-Old-Crate-3-FLASH.jpg)

It’s a hot, noisy walk back to Building 3 at Villaume Industries in suburban Minneapolis. The high-pitched whine of saws and pneumatics mixes with the smell of sawdust as employees build triangular wood trusses and crates.

In the back of the warehouse, between pallets of materials and the rollers where finished products exit, is a frame of a different sort: the shell of a World War II CG-4A glider. With its metal tube frame and precise, delicate woodwork, it’s right at home: In the early 1940s, Villaume was one of more than 16 U.S. companies contracted to build gliders designed by the Waco Aircraft Company.

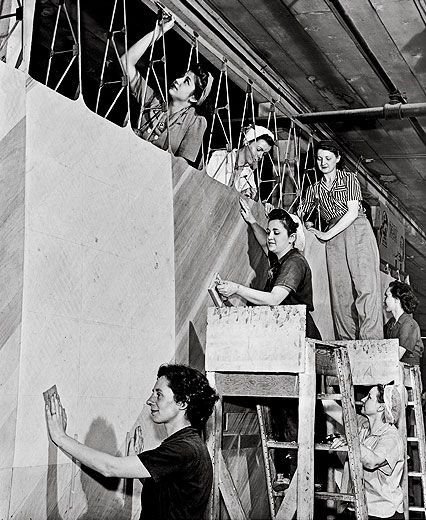

At the height of the glider boom, Villaume employed 1,500 people—mostly women—working three shifts, six days a week, to keep up with demand. They finished a glider every six days. Today, about seven volunteers with an interest in World War II show up every Tuesday and Thursday to connect the 72,000 parts needed to re-create a glider. It’s their tribute to this lesser-recognized World War II aircraft, and comes with the bonus of letting them work with an original manufacturer.

Villaume Industries is the classic immigrant success story: French-born Eugene comes to Minnesota and in 1882 opens a box manufacturing business. Business is good, and product lines expand to millwork, which is still the company’s product offering today.

The company’s initial contribution to World War II was thousands of K-ration cartons for the armed services; another major contract was for ammunition crates. Then, in 1942, Villaume won a bid as a sub-contractor to build the wooden components (wings, floors, control surfaces) for gliders that would carry paratroopers and equipment. A separate contract called for building shipping crates in which to deliver glider components overseas. Production ramped up quickly: In two months, Villaume increased its workforce tenfold. Most workers were new to the woodworking business, and learned how to build the gliders from military personnel.

“This wasn’t furniture, it was aircraft,” Linsmayer says. “Men’s lives depended on the quality of what we were doing.”

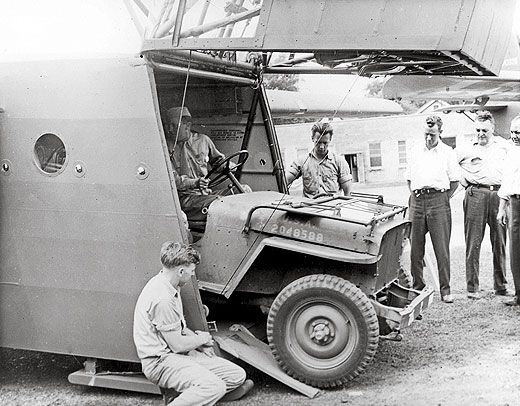

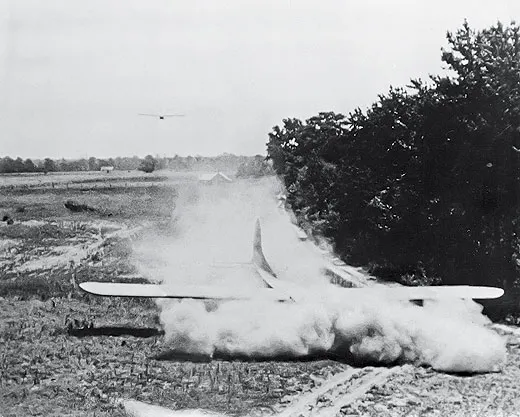

Gliders were used primarily in the European theater as disposable aircraft, towed to their destinations largely by C-47 Dakotas, the military version of the Douglas DC-3. Less expensive than powered aircraft and stealthier—at least in audio signature—they held either 13 soldiers and their equipment or a full-size jeep. Villaume built around 11 percent of the 14,000 gliders produced nationwide. Most went to the Army Air Forces and the Royal Air Force; the Navy took 13. Linsmayer knows of only a handful of original gliders still in existence. Once they had completed a mission, he says, local residents used them for firewood or building material (see “A Waco’s Happy Ending,” Aug./Sept. 2002).

When the war ended, Villaume went back to its previous business, and gliders became just a footnote in company records—until World War II buffs began contacting Linsmayer for information. Glider history, especially Villaume’s involvement, became his passion. When aircraft restorers Jim Johns and Ingemar Holm approached Linsmayer in 2007 about re-creating a glider, he offered warehouse space and donated much of the wood needed as raw material.

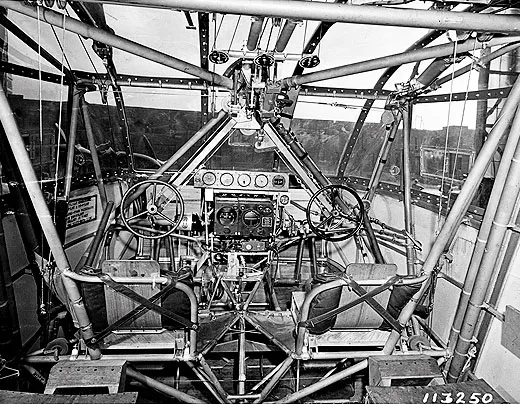

Johns and Holm collected vintage glider parts from military salvage yards, including frame pieces, instrument panels, and an original long, narrow box for barf-bag storage (troops seated aft of the center of gravity frequently succumbed to airsickness). They’ve found a roll of the original fabric used to cover wings and fuselage. They’ve fabricated the remaining parts based on original blueprints, some with print so tiny that Holm needs a magnifying glass to read it.

Of the volunteers, most of whom learned of the project through the World War II Roundtable network, some are retired military; one flies modern gliders. Dale Johnson is a master woodworker who can create exact replicas of wooden parts. Joe Messacar is a former aeronautical engineer who keeps the construction to perfect spec. Marilyn Curski is especially talented at intricate detail work.

When completed, the glider’s wing will stretch nearly 84 feet. Its interior structure looks like wooden lace. To save weight, most wooden parts of the original gliders were glued together, including the honeycombed floor of the passenger space, so the team is doing the same. Where the originals used screws, however, the team is in some cases substituting cotter pins.

While the group is trying to produce as authentic a re-creation as possible, they’re not making it airworthy—although they have a bit of insight into what it would be like to fly one. Newsman Walter Cronkite, who landed in a CG-4A in the Netherlands in September 1944, later described the experience as “like attending a rock concert while locked in the bass drum.”

When the re-creation is complete, the brand-new glider will likely be on public display somewhere near its Villaume home.

Minneapolis-based writer Lynn Keillor has a new respect for glider pilots, passengers, and Walter Cronkite.