Class of ’59

No buildings, no flight lessons, no problem. Some 60 years later, the first Air Force Academy cadets look back.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/19/18/19181458-ad66-4aae-9fab-db5844b18d94/11b_sep2016_usafacademytoday_live.jpg)

Jim Reed was a high school senior in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in the spring of 1954 when he heard the news. The U.S. Air Force Academy would be accepting its maiden class, scheduled to begin in July 1955. Students aspiring to a West Point or Annapolis appointment had been preparing for years, but Reed, who had already applied to the University of Michigan to study engineering, had to act fast. “I had never given any thought to joining the Army or Navy,” he says. “But I had a science teacher who knew I had a great interest in flying, and he gave me information about the academy.”

As word spread across the country, young men—some focused, some footloose—seized the opportunity to join the class of 1959, the academy’s first to graduate. In Minnesota, Pete Winters was dazzled by the first light of the supersonic age: “Chuck Yeager had broken the sound barrier and the X-airplanes were just amazing,” he says. “I had never piloted a plane when I got to the academy. But I already had it in my mind that I wanted to be a test pilot.”

On an aircraft assembly line in New York, Art Elser just wanted a second chance. “I had flunked out of MIT the year before,” he says. “Working at Grumman, building F-9s, I looked around at the older men there and decided I didn’t want to spend 30 years doing what I was doing. I applied to the academy with little hope of being accepted.”

Each U.S. senator and representative in the 48 states nominated up to 10 candidates to take the academy entrance exam. Of 6,000 applicants, only 306 top scorers were admitted. For the ’59ers, acceptance day would mark a stark transition and become a reference point for life.

**********

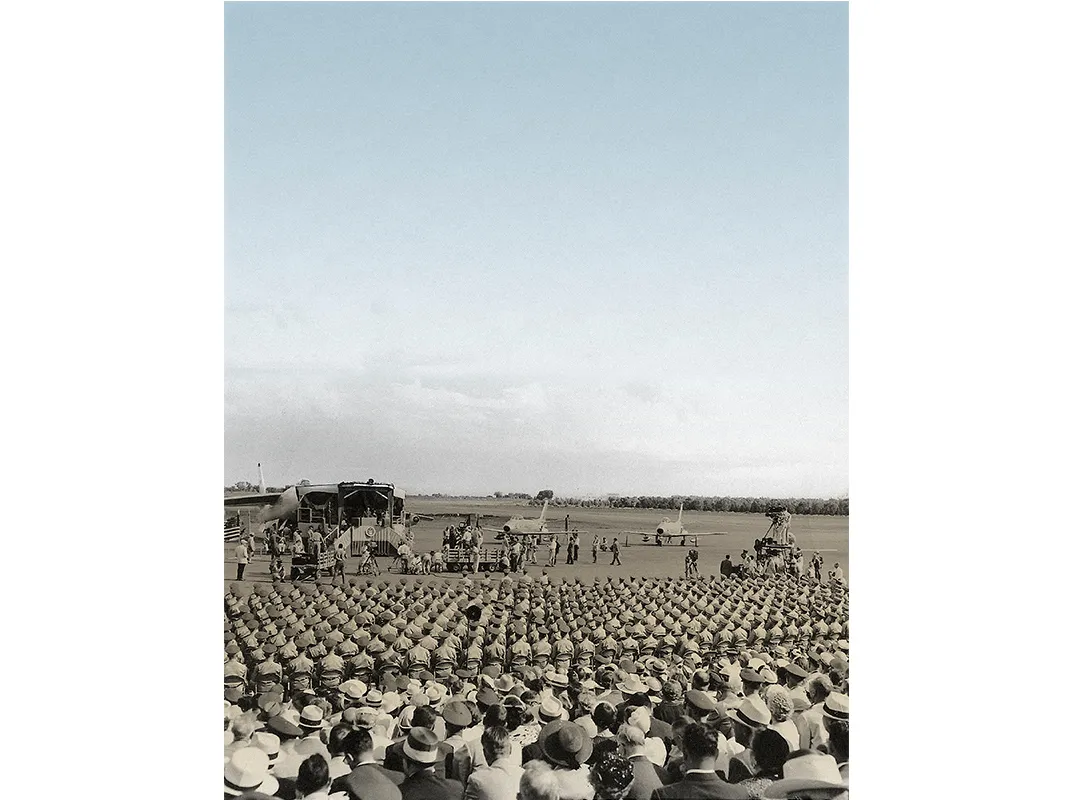

Dedication Day, July 11, 1955. A youthful Walter Cronkite anchors live black-and-white TV coverage. Overhead, seven B-36Ds—six-engine, jet-assisted messengers of early cold war might—plow through Rocky Mountain airspace. At attention in crisp new uniforms, teen cadets whose faces divulge little about who they would become: several four-star generals, an academy commandant, an astronaut, 14 test pilots, two Thunderbird pilots, one Rhodes Scholar, a Nixon White House aide. Here’s Valmore Bourque; at 6 a.m. he was the first kid in line to take the academy Oath of Allegiance. He’ll also be the first academy grad to die in combat—years from now in Vietnam.

Wild Blue U, as the school will one day be dubbed, this is not. Nor is it the academy depicted in glossy Architectural Digest spreads. That timeless aluminum and glass statement, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, will open three years later in Colorado Springs, barely in time for the ’59ers’ final year.

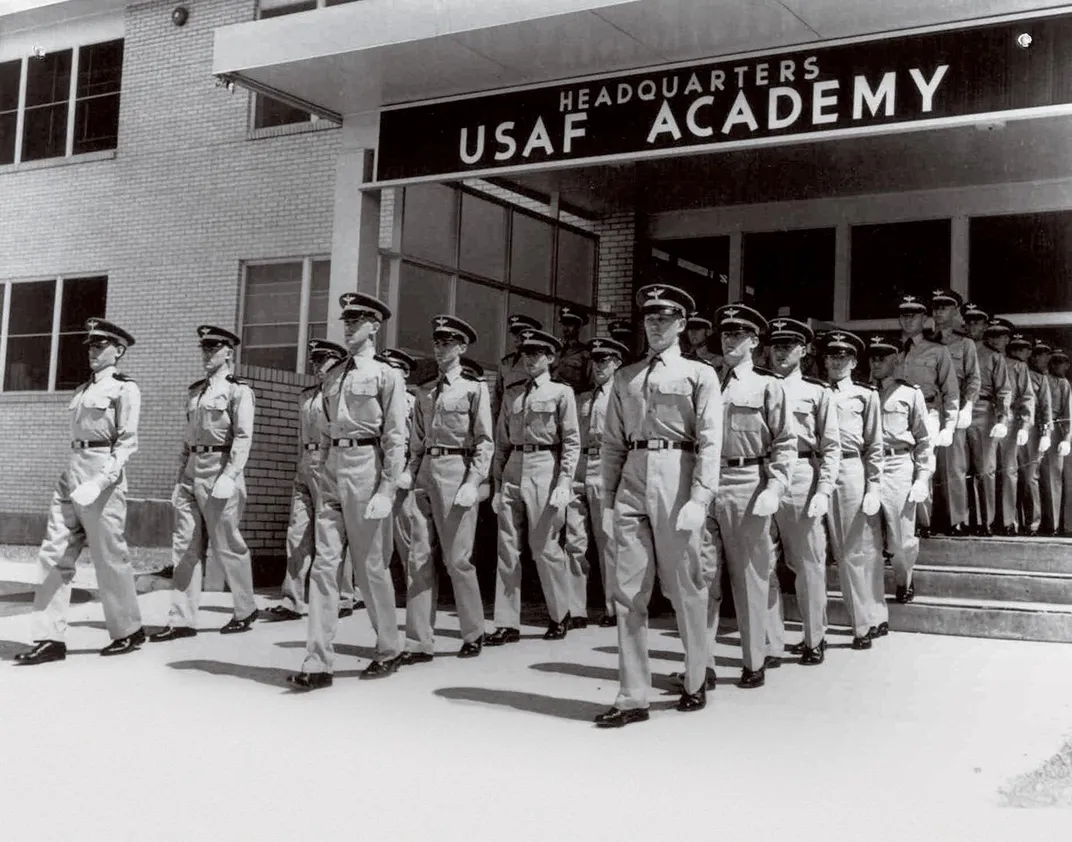

The incoming cadets of 1955—called doolies—reported instead to temporary facilities at Denver’s Lowry Air Force Base. “Wooden, two-story barracks, exact replicas of those in every World War II movie,” Jon Shaffer recalls. A million-dollar makeover lent the old base a scholastic, though not exactly Ivy League, veneer. Three academic buildings surrounded a grassy quadrangle where a red Matador missile—the 1950s forerunner of cruise missiles—assumed a skyward attitude. The complex included classrooms and science labs, a refurbished gymnasium, and a 500-volume library. In the barracks, each room accommodated two cadets, with twin beds, two desks, and a closet. Nobody mistook Lowry for the stone towers and expansive lawns of West Point. On the other hand, Bob Oaks says, “I don’t remember anybody sitting around complaining about what we didn’t have.”

One element was conspicuously absent: upperclassmen. At military academies, second-, third-, and fourth-year cadets traditionally lower the boom of indoctrination and discipline on the incoming class. Instead, the ’59ers got surrogate upperclassmen known as ATOs.

Air Training Officers were active-duty Air Force second lieutenants. “I had graduated from West Point, got my wings, and was at Tyndall Air Force Base waiting to go into all-weather fighters,” says Ray Battle, one of the first wave of ATOs. “The word came down that they were looking for young unmarried lieutenants to play the role of acting upperclassmen.” Sixty-six ATOs were brought to the academy, two assigned to each group of 10 cadets.

“They got to know us well and we got to know them very well,” Battle says. “We were always on duty, 24/7. Any time the cadets were out of their room they were subject to discipline, maintaining proper posture, and no talking among themselves allowed.”

The ATOs were trained for the mission. “We tried to maintain an atmosphere of order, yet still create something that wasn’t a duplicate of West Point or Annapolis,” Battle says. “We wanted something that was unique and as much Air Force as we could make it.” He notes that the workaday Lowry environment immersed cadets in the sights and sounds of military aircraft landing and taking off around the clock. In addition, academy jargon was Air Force-specific. “All military academies have their own lingo,” he says. “We tried to develop a language that was distinctly Air Force. For example, instead of telling a cadet to walk somewhere, we’d tell him to taxi somewhere.” Hot coffee in the dining hall was “JP-4”—jet fuel. Doolies were expected to know all verses of “The Air Force Song,” not just “Off we go into the wild blue yonder.” On a more practical level, cadets took navigation classes and on completion could proudly wear regular Air Force navigator wings. Battle says ATOs also encouraged cadets to adopt the academy honor code as their personal philosophy. “We wanted to instill in them a strong sense that the Air Force was uniquely their branch of the service,” he says.

Sixty-one years on, however, 1959 grads recall the less nuanced methods. “You’d be standing out at reveille formation,” Art Elser says of one memorable ATO. “You’d hear the screen door slam. He had metal taps on his heels, so you could always hear him coming clear across the quadrangle. You could just feel everybody tense up because you knew he was gonna be screaming in somebody’s face. In less than 30 seconds, he would find some reason.”

“It was dramatically different from Brigham Young University, I’ll say that,” Bob Oaks says. “Every step you took, you were told to take. I just got in line and did what I was ordered to do, like everybody else.”

Pete Winters details the daily drill. “Your room had to be spotless. Bed made so you could bounce a quarter on it. You ran everywhere. The ATOs marched us to breakfast, lunch, and dinner. You ate sitting at attention on the edge of your chair. You couldn’t talk, except to answer questions fired at you.”

All part of the plan, Ray Battle says today. “The first year was designed to be tough. So, we were tough on them. We wanted to teach them early on how to handle stress.” Any cadet who blanked on a question an ATO launched at him in the dining hall had to put down fork and spoon and contemplate it for a while. “But we always made sure everybody got a full meal,” Battle insists.

Under constant supervision, demerits accrued, and to walk them off, “tours” of the quadrangle (in full uniform, lugging a 10-pound M-1 rifle) multiplied. Still, the cadets developed a grudging admiration for the ATOs. Most training officers were fighter pilots, who exuded a confidence that cadets aspired to. Wide-eyed doolies got a demo flight in a T-33 jet flown by an ATO. “We’d put them in the back seat and take them up for an hour,” Battle says. “Let ’em fly a little bit and get the feel of it.” The alpha males wearing pilot wings also displayed other attributes esteemed by younger guys. “They drove nice cars and seemed to have beautiful girlfriends,” says Pete Winters.

**********

The Air Force was evolving into an aerospace force. In 1954, the Air Force Academy Planning Board was asked to decide what air cadets of the second half of the 20th century needed to learn. The committee determined that the academy curriculum should prominently feature the science and math fundamentals behind supersonic flight, space travel, and intercontinental missiles and nuclear weapons. Another large share of class and study time was claimed by world affairs, humanities, and foreign languages. Limiting energies to one major wasn’t permitted. “They wanted to give you a broad exposure, not particularly focused on one thing,” Karol Bobko says.

In contrast to Navy academy cadets, whose seamanship classes include hands-on experience crewing oceangoing craft, students weren’t given flight instruction, “though just about every guy in our class wanted to be a pilot,” says Jim Reed. In the summer after their sophomore year, cadets went on a field trip to an Air Training Command base, where they were offered 10 hours of basic stick-and-rudder instruction. However, formal flight training had to wait until they graduated from the academy and entered active duty. Concerns about distraction from the heavy academic regimen—as well as funding issues within the Air Force—kept undergraduate flight lessons out of the academy until 1968.

General George Fagan, a founding faculty member, later wrote of the stress piled high on that first entering class: “The courses had been overplanned, the demands on the cadets were too great, and practically every minute of the cadet’s day was scheduled, even his allocation of sleeping time.”

The rigors took their toll. One-third of cadets entering in 1955 failed to graduate—half of those bailing during the first year. “Most left because of the academics,” Bob Oaks confirms. “The requirements were demanding and there were a lot of them.”

For those that hung tough, however, challenge fueled motivation. “I never had a single thought about leaving,” says Karol Bobko, “It was just ‘Put your nose to the grindstone and press on.’ ”

**********

Like the selection of the falcon as academy mascot and the design of the Prop and Wings insignia, the cadet honor code was an exclusive product of the class of 1959. “It was our class that debated it, argued over it, and finally formulated it,” Jon Shaffer says. The one-sentence pledge—“We will not lie, steal, or cheat, nor tolerate among us anyone who does”—isn’t a commitment to the academy commandant, to the superintendent, or to God, he says; “it’s made to one’s fellow cadets.”

Seven honor code violations were recorded among the class of 1959, and all those convicted resigned from the academy. In the 1950s, Shaffer says, an honor code violation was “a terrifying mark to have on your record.”

The code passed down by the ’59ers is owned and operated by each successive class. Shaffer has volunteered as an overseer of honor code classes presented to incoming cadets; he laments the contemporary acceptance of mitigating factors and lenient sanctions, which he believes have diluted the code’s original high standards. “When you compromise your word of honor,” he says, “there can be no shades of gray.”

Those who survived first year would advance the next year to third-class (equivalent to sophomore), officially passing the doolie mantle, as well as the focus of ATO attention, to the incoming cadets who would make up the class of 1960. As the ’59ers matured into first-classmen (seniors), restrictions on social life—previously cadets were limited to ballroom dancing with young women bused in from a nearby college (hand-holding not allowed)—were relaxed. Weekend privileges were expanded, and near the end of the final year, cadets could own cars.

At graduation for the class of 1959, mountain weather abruptly turned cold and rainy, so the ceremony was moved inside the sparkling new Colorado Springs facility. Two hundred and seven graduates were commissioned as Air Force second lieutenants. Academy chaplains also performed 21 weddings.

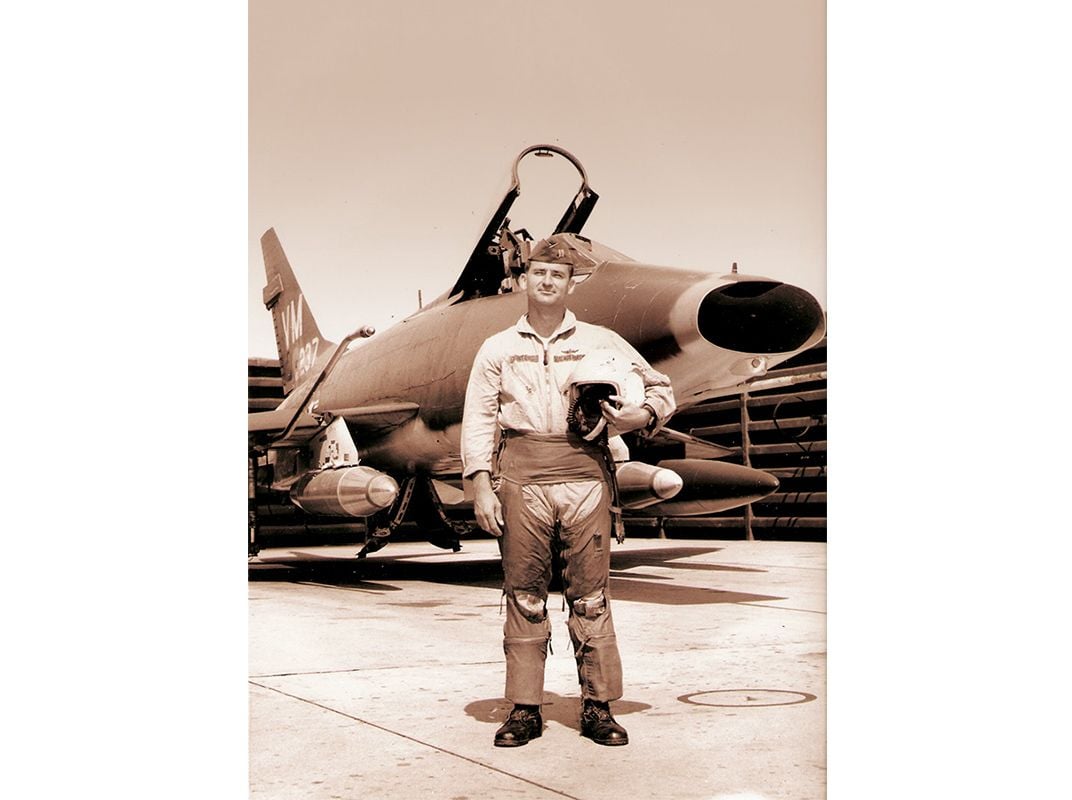

“By March or April of 1959,” Jim Reed says, “those of us who were going to be pilots already knew where we were going and when we would be there.” Academy graduates dispersed to Air Training Command bases across the country for a year of pilot training: a few months in prop-driven Beechcraft T-34 trainers before moving to the Cessna T-37 jet trainer or North American T-28, followed by six months in the Lockheed T-33. Then came advanced training in such aircraft as the North American F-100 Super Sabre, the single-seat fighter standard of the late 1950s/early 1960s, and the Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker.

As the first academy grads to mainstream into active duty ranks, ’59ers recall a smooth transition and no resistance from Air Force regulars. “Our class was very aware of being the first graduating class,” Jim Reed says. “Most of us felt this put an added responsibility on our shoulders, while in school and also during our early assignments. If we failed, it was also the academy which was on trial.”

**********

Sworn into the academy during mid-’50s tranquility, the class graduated straight into ’60s tumult. From nuclear nail-biting during the Cuban Missile Crisis to the space race to air combat in Vietnam—many classmates experienced a rapid immersion into careers unimagined in the old Lowry barracks.

“We graduated on June 3,” Bob Oaks says. “I got married on the 10th of June. I think I started pilot training on the 15th of August. When I entered the academy, I hadn’t given any thought whatsoever to how long I would stay in the Air Force. But once I graduated, I never spent five minutes of the next 35 years thinking about getting out.” During his career, Oaks flew F-100s in Vietnam—he was shot down by ground fire over enemy territory and plucked safely out—led fighter squadrons and wings, and rose to the rank of four-star general as Commander in Chief, United States Air Force in Europe. “At every assignment I had in the Air Force but one, I was happy to have at least one of my classmates from 1959 assigned at the same base,” Oaks says. “I actually had several of them work for me. We remain to this day a close-knit group, and I cherish that.”

After six years in operational squadrons, including 298 combat missions in Vietnam, Pete Winters finally became the test pilot he had dreamed of being as a cadet. At the Air Force Flight Test Center at Edwards Air Force Base, General Winters tested the handling quality on new fighter designs, including the famously temperamental F-111 he once had to eject from, and the user-friendlier F-15—as well as aircraft he still can’t talk about because of security restrictions. “The academy allowed me to fulfill my dreams,” he says. “If I’d followed some other path, I’d probably have ended up as a professor somewhere, like my father.”

“I had six nuclear bombs on my B-52,” says Jon Shaffer. “Our job was to wait until we got the Go Code.” As a B-52 bomber pilot for the Strategic Air Command, Shaffer was increasingly conflicted by what he perceived as a deliberate no-win strategy in Vietnam and a lack of candor from politicians managing the war. “As a young officer, I found that difficult to understand when American boys were spilling their blood,” he says. Standards instilled by the academy honor code compelled him to rethink his own involvement. In 1967, Captain Jon Shaffer resigned from the Air Force. He is now retired from a 28-year career as a United Airlines pilot.

“I got to do so many things a young man from Walla Walla could never imagine,” Bob Beckel says. A standout student athlete, Beckel is rated by ESPN as the finest basketball player to emerge from the Air Force Academy. Off the court, Lieutenant General Beckel scored highly too, flying over 300 missions in the F-100 in Vietnam and earning a Silver Star. He performed as a solo pilot in the Thunderbirds, the Air Force demonstration team, headed the Strategic Air Command refueling tanker force, and commanded the Seventh Air Division. In 1981, Bob Beckel returned to the Air Force Academy as commandant of cadets.

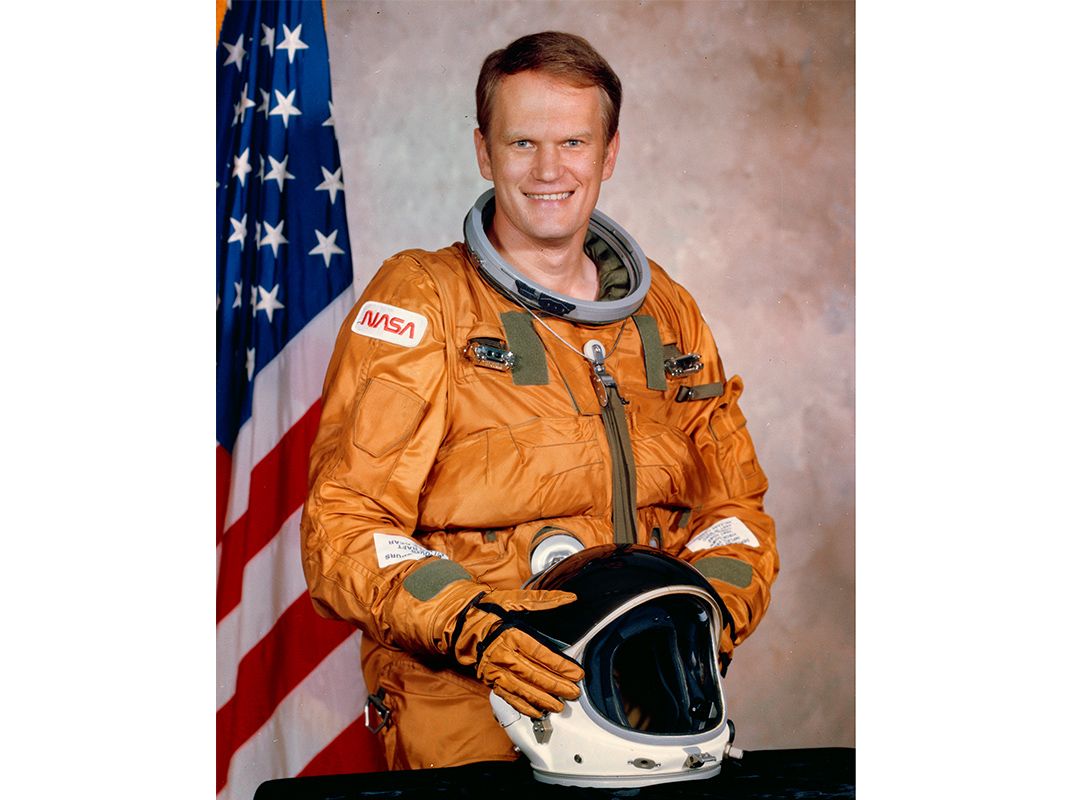

“I always said that, whatever opportunities for me arose, I would always choose the path that led me toward space,” says Karol Bobko. The first academy graduate to leave the atmosphere, Colonel Bobko was pilot on the space shuttle Challenger’s first flight, in April 1983, and mission commander on Discovery and Atlantis shuttle flights in 1985. “Obviously, the academy prepared me for what I wanted to accomplish in space and in the Air Force,” he says. Today, Karol Bobko does outreach for the Simulation Laboratories at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California.

Art Elser’s career path followed an eclectic route from Colorado Springs. First, to the cockpit of a KC-135 tanker, then back to the Air Force Academy to teach. In 1966, he volunteered for Vietnam and flew over 400 missions as a forward air controller in the Cessna O-1 and O-2. After earning a Ph.D., he resumed teaching at the academy and writing and publishing poetry. Today, Elser is a retired lieutenant colonel, and his nostalgia for his cadet years is, well, muted. “Don’t get me wrong,” he says; “going to the academy was a wonderful opportunity. But it’s sort of like my year in Vietnam. Don’t ask me to do it again.”

Colonel Jim Reed flew KC-135 tankers and B-52s. However, much of his 34-year Air Force career was preordained years before, on an academy summer field trip. “In 1958 we traveled around the Far East,” he recalls. “When we got to Hong Kong, I looked around and said, ‘This is where I want to be and this is the job I want.’ ” Twenty-one years later, he got that job, becoming air liaison officer of the American Consulate General in Hong Kong. An academy education has become a Reed family tradition: Reed’s son, Colonel Scott Reed, is a 1984 graduate, and his grandson, Brian, graduated this year. Reed, who is compiling a history of the class of 1959, reports that 124 of his 306 classmates are still living. About 50 attended the 55th reunion in 2014.

“I was always proud of them,” ATO Ray Battle says today, recalling the young lives he sternly shaped 61 years ago. After their second year, the ’59ers assumed the role of upperclassmen to new cadets, and the Air Training Officers left the academy.

In a 26-year Air Force career, Battle, who retired as a colonel, flew F-4 Phantoms, along the way commanding a forward air control unit in Thailand—“Running up and down the Ho Chi Minh trail.” Among his pilots were two academy grads. “I kind of watched over them,” Battle says. “And they kind of watched over me.”