The Airport That Wouldn’t Die

An embattled Florida field had more than history on its side.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Today_Airport_Flash_AUG09.jpg)

From a long final for Runway 6-24, Albert Whitted Airport looks like an aircraft carrier on the glittering blue of Tampa Bay, neatly berthed alongside the modest skyline of St. Petersburg, Florida. The field is groomed like a fairway, its aprons and tie-down areas dotted with light aircraft that, while mostly middle-aged, seem freshly minted.

For some visitors, the tableau will evoke flying in the 1970s. Older hands may picture Betty Grable debarking from a Lockheed L-10 Electra. Why? Because this is what all city airports were once like: small, tidy, fairly busy, and, most important, downtown. Whitted is one of the last of its kind, a relic of a friendlier epoch of aviation.

The best view of the field is from Randy York’s Schweizer 300C helicopter. A compact, cheerful man, York has spent much of his life flying rotary craft, including two tours in Vietnam as a gunship pilot. Buzzing with him around St. Petersburg’s high-

rises, you see how the airport and city blend seamlessly. The airport’s east-west runway flows into First Street South only a few blocks from the heart of town.

When you mention the apparent blurring of boundaries, York dusts off the mother of all airport accessibility stories. An elderly couple, lost after leaving Tampa International, finally reached what they thought was the interstate. But the “freeway” turned out to be a runway, 18-36. Apparently undaunted, they drove their rental car off the end of the pavement and into the bay, where, luckily, police were staging maritime rescue drills.

Just outside the northwest corner of the airport sits one of the city’s water treatment plants, which, when the wind is right, makes its presence known. Next to that is a Coast Guard station, and nearby, a garishly decorated floating casino called Big Easy idles.

The airport’s 110 acres may be the most valuable property in St. Petersburg, the kind of waterside property that makes developers salivate. Land like this, they say, deserves better. But others think the land was meant to be an airport, a place where citizens can hang out and watch the airplanes, largely unimpeded. It’s not just an airport, they’ll tell you, it’s our airport.

The field has been a target almost from birth. In 1935, just as the airport’s operations were starting to grow, a local investment company wanted to turn the site into wharves. As early as 1940, the powerful St. Petersburg Times began a long campaign to get rid of the airport. In 1958, the city manager tried to close the field and allow development; a local pilots’ association coalesced to defeat his plan.

In 1982, a city council committee proposed peeling off some airport property for a convention center, and giving the remaining land to the nearby University of South Florida. The full council, however, backed the airport. During the dispute, defenders of the airport asked the mayor to form an advisory committee. The mayor demurred, urging instead the creation of a private committee that the city government could not load with its pals. The result was a 12-member firewall between the airport and city politics—a key factor in future battles.

All these were mere skirmishes compared to what was coming. A year after the 2001 municipal election, St. Petersburg’s economic development director, Ron Barton, floated a plan that would close the airport altogether, devote about 60 acres to a bay-front park, and use the other 50 for an “urban, mixed-use community.” The city council rejected the idea, inflaming its proponents, who quickly banded to form the Citizens for a New Waterfront Park.

In St. Petersburg, any change in the way waterside property is used requires an amendment to the city charter, via a referendum vote. To get the issue on the ballot, proponents must submit a petition signed by at least 10 percent of the voters from the last municipal election. By August 2003, the Citizens for a New Waterfront Park had the necessary 15,000 signatures and a secure place on the November ballot.

“It looked like they would win,” recalls Jack Tunstill, a longtime flight instructor who became one of the generals in the airport war. Now, against what seemed long odds, the airport side fired back. Almost overnight, yellow-and-black signs calling for citizens to support Whitted bloomed like fields of daffodils across Pinellas County. Randy York put a big one in the bed of his pickup and drove it around St. Petersburg. The Advertising Air Force, a company that flies banner advertisements, towed “Save Albert Whitted” signs from its airplanes for free. Money flowed in from the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association, which established a political action committee and paid for a consultant.

A potent community outreach effort got under way. Terri Griner, a petite kindergarten teacher who has a longtime involvement in local politics and a soft spot for aviation, became its mainspring. “We were very upset,” she says. “We asked people to join. We did the name [the Albert Whitted Airport Preservation Society], the logo, and everything right there on that dining room table. We began with three board members. Now it’s up to about 2,000 folks. Everybody in the community helped. We had a big meeting in the Marine Science Building and 300 people showed up. It was awesome.” Then they arranged a 75th anniversary airshow in October that wowed everybody, and earned money for the cause.

Bud Risser, who is on the airport advisory committee and owns a Piper Malibu Mirage and co-owns an Eclipse 500 light jet, recalls some of the council meetings: “One of the people there was a good-looking young black guy. He said, ‘I used to ride my bike to the airport to watch the planes. I’m now an airline captain.’ A woman said, ‘I’ve never flown in a plane, but I’ve taken my children, my grandchildren, and I will take my greats, to the airport.’ ”

St. Petersburg became bitterly divided. The airport backers dismissed their opponents as shills for developers. The park people said they were offering a better use of valuable land and that the talk about high-rises was bunk.

The University of South Florida, already bursting at the seams with students, wanted the east-west runway closed so the school could build taller buildings. So did Bayfront Medical Center, All Children’s Hospital, and the Poynter Institute, which is owned by the St. Petersburg Times. But any changes in how the property was used needed approval by both the Florida Department of Transportation and the Federal Aviation Administration, which effectively owns the runways. Anything done to extend a runway into the bay would bring in the Army Corps of Engineers, as well as state and federal environmental agencies.

James Bennett, chair of the St. Petersburg city council and also a pilot, contacted the FAA, which, he says, “had stopped funding [the airport]. It was in disrepair. When you take money from the federal government, you’re tied in for 20 years. The city had received tons of money from the FAA over the years,” so if the airport were reduced or closed, “we would have [had] to pay that money back.”

Mayor Rick Baker offered an alternative: Leave the airport with a single north-south runway, 18-36, extend it a few hundred feet into the bay, and sell off about 30 acres for development. A few pilots went along. “The idea was, they’re going to close the airport and there’s nothing we can do about it,” Tunstill recalls. But while the mayor’s idea served nearby property owners, it did nothing for the two main combatants. The park people would get nothing, and the airport would lose its long runway. Absent any compromise, the conflict settled into a winner-take-all contest at the ballot box that fall.

The airport people had no trouble finding their 15,000 signatures. Then, around midnight, just minutes before the October 1 deadline to get the issue before the voters, the airport advisory committee and city council agreed on the wording of the referendum questions and moved the airport to the top of the ballot. The first question asked if the airport should be kept open “forever.” The second, whether the city council should accept FAA grant money without consulting the airport’s neighbors. And the third, whether the airport property should be turned into a park, or divided along the lines the mayor suggested.

Like many people involved in the dispute, Risser is old St. Petersburg. “In 1959, I got my ticket here,” he says. “My dad flew out of here a decade or more before that.” But his perspective is also that of a prominent businessman. “When they started this effort, I thought they were wrong. The ‘forever’ thing. I thought they were really naive in their approach. So I commissioned my own poll. It said they were going to win.”

The Times differed. “One day,” a late-October editorial intoned, “St. Petersburg residents will tire of being denied use of more than 100 acres of public land…. They will tire of Federal Aviation Administration control of such valuable property…. They will tire of a noisy airport that restricts the neighboring university and hospitals, and that presents a growing pubic-safety threat to downtown residents.”

Strong stuff. But by the time the editorial appeared, the park forces, whose message had never quite jelled, had lost momentum. On November 4, 2003, in the biggest municipal voter turnout in 50 years, some 25,000 residents voted with the yellow signs: 72 percent wanted to keep the airport open, 67 percent favored the city’s accepting federal aid, and 78 percent voted against turning the airport into a park.

Howard Troxler, a Times columnist, summed it up: “There never was a clearer election result. The sun was not in anybody’s eyes…. It required 15,000 petition signatures just to get the park idea on the ballot; only 7,783 people actually showed up to vote for it.” Through the fight, Troxler had kept a black-and-yellow pro-airport sign on his office wall.

Bud Risser notes that the voters were not just supporting aviation. Crucial reinforcements came from a “number of other constituencies that had nothing to do with flying,” he says. “One group didn’t want to see high-rise buildings near the waterfront. Another group, in west St. Petersburg, worried that too much emphasis was on downtown.”

It was a resounding victory. “After the election, I looked at every precinct,” Risser says. “The one we didn’t carry, off the south end of the airport, was a 49-51 split. The demographics were everybody.”

To many residents, a vote for the airport was also a vote for preserving important aviation history. Ninety-five years ago, on January 1, 1914, a Benoist XIV flying boat lifted off from the bay front before a cheering crowd and flew the 21 miles across the water to Tampa. It was the world’s first scheduled airline flight. Young pioneer pilot Tony Jannus became the world’s first commercial airline skipper and Mayor Abram C. Pheil the first scheduled-airline passenger. A flying replica of the Benoist, built for the 75th anniversary of the first flight, hangs in the St. Petersburg Museum of History not far from the airport.

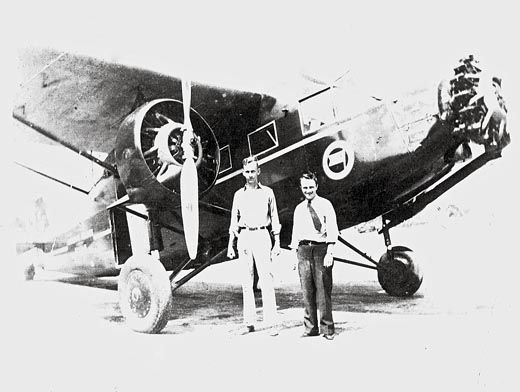

James Albert Whitted became the local face of aviation. During World War I, he’d been one of the first pilots in the U.S. Navy, teaching at Pensacola and flying from the improvised carrier Langley. After the war, Albert began designing and building airplanes with his brother Clarence, a talented mechanic. Together, they built two pusher-type seaplanes, the Bluebird and the Falcon.

“My dad was a genius on any kind of engine,” says Eric Whitted, a retired educator who has become keeper of the Whitted brothers legend. Then, as now, flying was great fun, but not necessarily a living. “Albert didn’t have to work,” his nephew explains. “My grandmother owned most of the real estate around Central Avenue.”

In mid-August 1923, while Clarence was grounded with a broken arm, Albert took four passengers up in the Falcon on a flight to Pensacola. The prop threw a blade and the airplane crashed, killing all aboard. “My dad never fully recovered from Albert’s death,” says Whitted. In 1928, the city opened the airport that bears his name.

In 1929, the Goodyear blimp came to visit, and ended up staying. A huge hangar was raised. It looked like the beginning of a golden age. Unfortunately, the Great Depression was right behind it. By April 1930, all the banks in St. Petersburg had closed, and Goodyear retrieved its airship. All that remains of the blimp are two iron tie-down rings planted in concrete blocks.

Despite the hard times, the city built Hangar One in 1931. Three years later, a young Chicagoan named Ted Baker (no relation to the current mayor) moved in with two used single-engine, four-passenger Ryan Broughams, a skeleton staff, and a government-awarded franchise for the 142-mile St. Petersburg-Daytona Beach mail run. Baker’s outfit was the forerunner of what would become National Airlines, the nation’s seventh largest carrier before it merged with Pan American.

The airport continues to draw visitors, many of whom stay. Henry Van Kesteren, known as Van, first visited Whitted in 1962, while ferrying his family in a Piper Apache from his Air Force assignment in Suriname to a new post at Travis Air Force Base in California. “We landed in Miami to clear Customs,” he recalls, “so I said, ‘Let’s run up to St. Petersburg.’ We stayed at a little hotel across the street. Borrowed a car and toured around. I thought, ‘What a neat little town,’ not knowing I would come back.”

His last posting turned out to be MacDill Air Force Base, across the bay. When his military career ended in 1969, he and wife Ginny, also a pilot, settled into St. Petersburg and immersed themselves in Florida’s real estate boom. Their business card advice: “Let us show you from the air.”

When Bay Air Services, the airport’s fixed base operation, came on the market in 1973, Van Kesteren purchased it with a partner, whom he bought out a year later. He ran Bay Air until 1987, owning and flying just about everything that flew. He was also active in developing supplemental type certificates, which the FAA issues for product modifications. “It’s like a patent,” he explains. His certificates have included composite props for the Piper Malibu and Aerostar. Today his company, VK, Inc., occupies a big blue hangar on the north side of the field, home to a polished Aerostar, a straight-tail Beechcraft Baron, and a blond labrador named Rusty. “I just deal in airplanes that interest me,” says Van Kesteren, now a trim 88 with some 39,000 hours. His most recent acquisition is an Eclipse 500, which he owns with Bud Risser.

Ron Methot, a tall, rangy fellow, now runs Bay Air and St. Petersburg Flight Service. The time-honored tradition of washing and gassing and moving airplanes in exchange for flight time—extinct at many general aviation fields—is alive and well here. “We’ve got guys who were here pumping gas who [now] fly for airlines,” Methot says, who pumped gas himself there at 17. “I am sometimes referred to as a drug dealer, flying being the drug.” Today, he has logged about 25,000 hours. “I’ve always flown off this airport, and I haven’t flown what can’t come in here.”

That would include everything that needs more runway than the 2,864 feet of 18-36 and the 3,677 feet of 6-24. “Short runways mean we don’t have the corporate traffic that takes over an airport,” says Methot. “We have to rely on smaller aircraft users. We don’t sell enough fuel to do this for a living. It got tougher after 9/11.”

Randy York’s office is in another corner of Hangar One. “I’ve been here since August 1978,” he says. “I got my flight school approved in ’78, set up at Bay Air. A few months later, Van and I partnered up in the helicopter business.”

York bought the company in 1987 but continued to share Hangar One with Bay Air. “About six years ago, we had 20 helicopters from all over the world. I downsized.” West Florida Helicopters now operates four piston-powered Schweizers in Hangar One. “We do photo flights. Rebuild them for resale.”

An extension grafted onto the north side of Hangar One houses the cluttered upstairs office of airport manager Richard Lesniak, who came to Whitted after the 2003 referendum. He says revenues and rents earn the city $800,000 to $900,000 a year. Last year, the airport had 84,000 takeoffs and landings, with 185 airplanes and 300 jobs based there. “Since 2003,” Lesniak says, “the city has put about $7 million capital in the airport, another $4 million for a new control tower and taxiway improvement—$11 million in five years.”

Completed in 2007, the new terminal is named for John Galbraith, a former Marine pilot, and his wife Rosemary, a former flight attendant. Galbraith moved his investment firm to St. Petersburg because he could fly in and walk to his Bayfront Towers condo. Over the years, his philanthropic impulse pumped millions of dollars into a host of causes, including the airport.

When city playground money became available, Terri Griner, now president of the Albert Whitted Airport Preservation Society, put in a bid to create an aeronautics-theme playground by the control tower. The park, which seems to be always full of children, has a jungle gym modeled on the medevac helicopters that fly from the airport, swings with a blimp motif, and miniature airplanes on spring stands.

The Albert Whitted Airfest, Inc., an annual airshow, earned a small profit in 2006. But in 2007 it lost money, so last year’s show was canceled. The next St. Petersburg Airfest is set for October 23 to 25.

The preservation society has about 30 unpaid volunteers, including Griner, and a pool of perhaps 100 more for special projects. Pancake breakfasts are offered the first Saturday of every month, in tents set up outside the group’s headquarters. “We market the airport,” Griner explains. “We hand out welcome bags in the terminal, with city maps and so forth. We provide all the tours.” They also got Hangar One named an historic landmark, putting another obstacle in the way of those who would try to close the airport.

The most interesting airplane at Albert Whitted may be the red WACO UIC biplane in Tom Hurley’s hangar. This is his second WACO; its predecessor was an open-cockpit UPF-7. The UIC’s enclosed cabin attracts people who want to fly in an old biplane, but don’t want to be blown around.

Hurley is a big, sometimes gruff man whose hands are scarred and stained from the labor of keeping NC13562 flying. Today, he is putting it back together after the annual inspection. Hurley takes people out for hops of various magnitudes, flying low enough for passengers to get biplane experience and for people on the ground to read the big “BIPLANE RIDES” painted on the lower wing’s underside.

Keeping an airport like Albert Whitted alive is not unlike caring for a 75-year-old biplane. History suggests that for downtown airports, “forever” may really mean “for now.”

“The 2003 referendum was very convincing,” says Methot. “We’re accepting federal funds, which obligates us for 20 years. But I don’t think any airport is safe in this country. All it would take to close the airport would be a new referendum.”

Frequent contributor Carl Posey recently wrote features about F-105 Thunderchiefs and the Spanish Civil War.