The Bear Is Back

The winning-est Bearcat in air racing steps up once more to the starting gate.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Today_Bear_Flash_ON09.jpg)

After a winter spent licking the wounds from battles lost last fall, the Bear stirs, indifferent to the bracing wind and brilliant sunshine. It emerges slowly from its cave, pauses to orient itself, then gravitates toward its natural hunting ground: not a forest or a river full of salmon but the ramp of the Reno-Stead Airport in Nevada. Here, for four decades and counting, the Bear has stalked its prey: Sea Furys, Lightnings, Super Corsairs, and, tastiest of all, the fleet, slender thoroughbreds known as P-51 Mustangs.

“God, it’s just such a big, handsome, good-looking critter,” says crew chief Dave Cornell as he watches the freshly painted airplane roll past the lesser creatures parked nearby. “It’s got a fine wing and a ferocious engine, a sturdy and rugged landing gear—everything you need for air racing. The Mustang has a wonderful laminar-flow wing, and it would be fun to race. But just in terms of going around Reno, it’s really tough to beat the Rare Bear.”

Seldom has a warbird been more aptly named. Packing up to 4,500 horsepower in a muscular 8,700-pound package, Rare Bear is a radically modified, one-of-a-kind version of a Grumman F8F-2 Bearcat. It has won more Unlimited races than any airplane (the Unlimited category is open to any piston-driven aircraft with an empty weight greater than 4,500 pounds, typically stock or modified World War II fighters). Rare Bear also holds the three-kilometer speed record—528.33 mph—making it the fastest piston-powered, propeller-driven aircraft in the world. But what sets the Bear apart from its rivals is the cult that surrounds it.

In a milieu dominated by million-dollar airplanes and zillionaire sportsmen, Rare Bear has been the people’s choice, the low-buck underdog that triumphed against all odds. The team has made ends meet by selling not only T-shirts but also used engine oil (marketed in vials as “Bear Blood”), and the vast majority of people who have worked on the airplane have been volunteers. “There were times when I stayed on after the races and washed down the airplane myself because everybody else was so worn out,” says Chris Rakestraw, a retired TWA flight attendant who now works as the team’s administrative coordinator. “I understand that it’s just a piece of metal. But it’s taken on a life force of its own.”

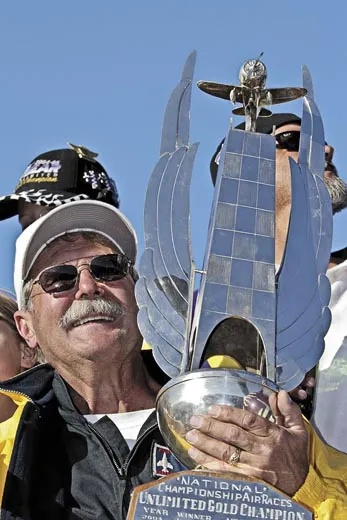

For most of its life, the Bear exuded the can-do personality of longtime owner Lyle Shelton. A naval aviator turned TWA pilot, Shelton plucked the derelict Bearcat out of an Indiana weed patch in 1968. Then he begged, borrowed, and promoted like crazy to customize the airplane with an oversized Wright R-3350 radial engine, transforming the wreckage into a winning racer. Even the people who know him best are mystified at how he accomplished so much with so little. But Shelton didn’t just own the Bear; he flew the bejeezus out of it, collecting six Golds at Reno as well as winning races at Mojave; Miami; Hamilton, California; and Cape May, New Jersey. “It was a big part of my life,” says Shelton. “The Rare Bear project was probably the most riveting that I ever got into. We didn’t have big investors or big sponsors. We just did it because we wanted to do it.”

Shelton belongs on the short list of greatest air racing pilots ever. But what made him such a crowd favorite was how he won his races. “Fly fast” was his motto. When he retired, he turned over the flying duties to another military-aviator-turned-airline-pilot, John Penney. Although Penney didn’t have Shelton’s swagger, he scored back-to-back victories in 2004 and 2005. But money was tight. Shelton had no personal fortune to draw on, and sponsors were impossible to find. An engine meltdown in 2006 seemed to be the end. But the Bear has always depended on the kindness of strangers, and so it proved then, in the form of San Antonio oil man Rod Lewis.

“I think I’ve been to every Reno air race since ’95,” says Lewis, a major-league warbird collector who owns three stock Bearcats and Glacier Girl, the world’s most famous P-38 (see “Glacier Girl,” Feb./Mar. 2004). “I’ve always liked the sound of Rare Bear, and I’ve always liked the look of Rare Bear. Sometimes we’d see it race, but not all of the time, because of, ah, economic issues. It was a really lean, low-budget operation. Some years I’d see Lyle sitting there with a coffee can, looking for donations.”

In 2006, after several months of negotiations, Lewis bought the Bear, paying just under $2 million. Since then, he’s spent almost $2 million more refurbishing and upgrading it. In 2007, Penney rewarded Lewis’ largesse with a Cinderella win at Reno. But last year was a nightmare. The spray-bar oil cooling system ran dry after a qualifying heat during the week, and the engine overtemped, setting it up for failure. Sure enough, on Sunday, Penney started the Gold race down on power, and the engine blew before he reached the finish line.

Modified 3350s don’t grow on trees, so there’s plenty to do before the Bear can race in 2009. Here in Reno, the work is coordinated by team manager Alby Redick. Twenty years ago, he helped start the movement to import Soviet bloc jet fighters to the States. (He still runs a company called Aviation Classics Limited, known informally as MiG Alley.) But his father was a mechanic at what’s now the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino, California, so he grew up surrounded by World War II aircraft.

“When my father would ask me what I wanted to do, I’d whisper, ‘I want to sit in the Bearcat,’ ” Redick recalls. “I know it’s not a consensus view, but I think it’s prettier than the P-51. And there’s something about the mixture of 60-weight oil and avgas coming out of a round motor. I could stand in back of one and”—he inhales deeply—“all day. And the sound! I don’t care who are you. You stop and look around when the Rare Bear is flying.”

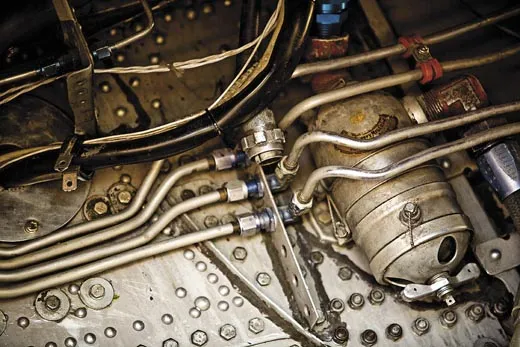

In Reno, Redick has two mechanics, Keith Geary and Robbie Grosvenor, working full time on a boil-off oil cooling system and other Bear-related tasks. But the rest of the project is being farmed out all over the country. Crew chief Cornell is building a new engine in Oregon. Clark Thompson is designing a telemetry unit in New Mexico. Executive Propeller is overhauling the prop in California. If all goes well, the Bear will be buttoned up early enough to enable Penney to get in a few hours of flight testing before the mid-September races.

But prepping a warbird for Reno is always a crapshoot. As the crew members work through their scrupulously detailed checklists, countless gremlins wait to foil them. And when you’re talking about a warbird, no problem is small. Parts aren’t available at the local Sears. In many cases, just unscrewing bolts and prying apart components require special tools. As the race deadline approaches, the job almost inevitably devolves into a thrash. Work hours accumulate. Frustration grows. Tempers flare. Are we having fun yet?

But that moment, if it arrives, is several months away. On this sunny day in late April, everybody is all smiles as they watch the resplendent airplane being towed from the cramped hangar that had been its home to a spacious new Bear cave elsewhere at the airport. Watching the airplane move past a pair of MiGs, Cornell has a proprietary gleam in his eye. He started working on the Bear as a volunteer in 1978, then in the late ’80s served as the crew chief before getting crossways with Shelton and leaving to work on Mustangs and Sea Furys. Rod Lewis re-hired him in 2007, and he’s been on Bear patrol ever since.

“Since I’ve been on this project, I’ve pretty much worked 12 hours a day, seven days a week,” he says. “I’ve taken a few days off. But not very many. Maybe 10 in three years. So I’ve spent, and this entire team has spent, just a huge amount of time to get this baby back to where it used to be. And it’s back.” He laughs like he really means it. “The Bear is back.”

It’s hard to imagine now, when air racing is treated like an exotic curiosity, but there was a time, in the 1930s, when the sport attracted so much attention it made aviators such as Jimmy Doolittle and Roscoe Turner national celebrities. But after World War II, air racing faltered. In 1964, Bill Stead resurrected the sport, staging a race over a pylon-delineated course at a remote airfield near Reno. The spectators for the inaugural event included a 31-year-old U.S. Navy lieutenant who was there in part because he’d been so hungover he’d missed his flight to Hawaii. His name was Lyle Shelton, and in Reno, he discovered a passion that was to animate the rest of his life.

That first year Shelton worked as a volunteer on a couple of Unlimited aircraft. During the 1965 off-season, acting on the advice of Alby Redick’s father, he persuaded a warbird owner to let him race a stock P-51D. To drum up sponsorship, he flew the Mustang to Tonopah, Nevada, made a screaming low-level pass over town—inverted—then landed and passed the hat at the local businesses. According to Shelton’s good friend Dell Rourk, who wrote Racing for the Gold: The Story of Lyle Shelton and the Rare Bear, his biggest benefactor was the madam of the town cathouse. In her honor, he named the airplane Tonopah Miss. In his first race at Reno, Shelton finished at the back of the pack.

In those days, warbirds were selling for peanuts. Even so, Shelton couldn’t afford a flyable one. So in 1968, during a TWA layover at Chicago O’Hare Airport, he drove to Valparaiso, Indiana, to check out a wrecked Bearcat. The pilot had botched a landing and the airplane had cartwheeled. For six years, it had languished in two sections. The engine, wingtips, right landing gear, instruments, cockpit controls, and several other critical systems were missing. The owner was asking $2,500. Sold!

Toward the end of World War II, Grumman designed the Bearcat as a replacement for the U.S. Navy’s F6F Hellcat fighter, and the Bearcat was revered for its superb maneuverability and climb rate. The winner of the first air race at Reno was a stock Bearcat flown by Mira Slovak, and the Unlimited class, starting in 1965, was dominated by Bearcats flown by Darryl Greenamyer. (One of his aircraft, fittingly named Conquest 1, is now on display at the National Air and Space Museum.) Relying on the racing verity that there’s no replacement for displacement, Shelton planned to beat Greenamyer by replacing his aircraft’s original engine, a Pratt & Whitney R-2800, with a more powerful modified Wright R-3350.

On a rainy December afternoon in 1968, Shelton and Cliff Putman, crew chief at the time, trucked the Bearcat to an airport in Compton, south of Los Angeles. Bill Hickle, a Northrop structures engineer and wannabe air racer who rented a hangar at the airport, saw them roll up. When he walked over to investigate, Shelton asked him if he knew anybody with a welding rig.

“Well,” said Hickle, “I’ve got a welder over in my hangar.”

Shelton: “We need some repairs to this thing. Do you know anybody who could do it?”

Hickle: “Basically, that’s what I do for a living.”

He went to work on the airplane, first doing structural analysis, later as crew chief. Now 69 and white-haired, running an aircraft service and repair business, Hickle still volunteers to work on the Bear even when it means making paying customers wait. “I haven’t seen every flight in between,” he says, “but I’m the only one that I know of who’s seen the first flight and the last flight. I’ve been 40 years on the Rare Bear, and I’ll not get involved with another airplane. This is the one that’s got my attention. It’s like my only child.”

The Bearcat was painstakingly reconstructed with a donated R-3350 engine of unknown provenance shoehorned into the cowling. Nine months after he had trucked the wreck to Compton, Shelton flew the airplane to Reno for the 1969 races. Hickle remembers people looking at the big engine, shaking their heads, and muttering, “You stupid suckers.” Nobody in air racing had tried such a radical conversion before, and the Wright radial was still dogged by a reputation for setting B-29s on fire during World War II. Sure enough, the first engine blew up. In 1970, another 3350 of uncertain vintage also went kerplooey.

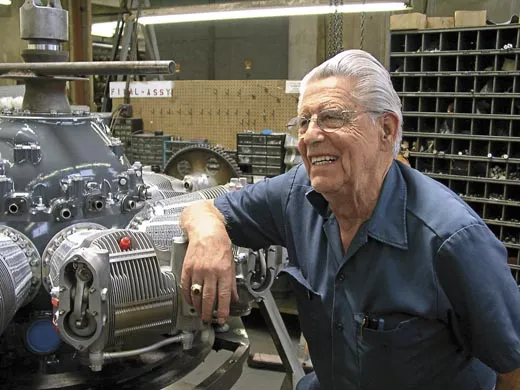

For the 1971 race, Shelton got an engine customized by Mel Gregoire, who had been servicing Wright radials since 1950. Gregoire worked for Aircraft Cylinder & Turbine in Sun Valley, California, and company owner George Byard donated the engine to Shelton. “I don’t know if there’s anybody alive who’s worked on those engines longer than I have,” says Gregoire, who is, at 91, still Cornell’s guy for engine advice. Gregoire knew that during the 1950s and ’60s, ultra-rugged versions of the 3350 had been developed for airline and military use. The engines were too big and heavy for air racing, but their pieces were stout enough to withstand extreme stress, so Gregoire mixed and matched components to create a one-of-a-kind monster. From a Lockheed L-1649 Starliner, he took a nose case designed for a slow-turning prop and mated it to the so-called power section—crankcase, crank, pistons, and cylinders—lifted from a Douglas DC-7 (which also provided the Bear’s engine cowling).

Shelton and the hot-rodded Bear won their first race at Cape May in 1971, then, beginning in 1973, finished first three times running at Reno (though he was disqualified in 1974 for not pulling up during a caution). But boom was followed by bust. After a blown oil line, then a gear-up landing at Mojave in 1976, there was not enough money to repair the airplane, so the Bear sat forlornly at Van Nuys Airport, without an engine or obvious prospects.

One of the witnesses of that spectacular gear-up landing was Dave Cornell, attending his first air race. A self-taught engineer who created special effects for the movie industry, Cornell saw the airplane again a few years later while he was taxiing at Van Nuys Airport during a flying lesson. He volunteered to help get the Bear back in the air, and he apprenticed with several of the aging wizards of air racing. But even pumped with plenty of nitrous oxide and a witch’s brew of nitromethane, Rare Bear couldn’t keep up with newer, more sophisticated warbirds. “It dawned on me that if we were going to get in the hunt, we needed a much more powerful supercharger,” Cornell says.

He snagged a blower from a Lockheed EC-121. The supercharger had been designed for direct-head fuel injection, a technology that wouldn’t fit inside the Bear, so Cornell re-engineered the supercharger to work with the existing pressure carburetion system. Normal rated power of a stock 3350 was 2,800 horsepower at 2,600 rpm and 45 inches of manifold pressure. With Cornell’s mods, the engine made 4,000 ponies at 3,200 rpm and 80 inches of manifold pressure—4,500 horsepower with a shot of nitrous. With that engine and a slicked-up airframe, Shelton kicked holy butt, demolishing the three-kilometer speed record and dominating at Reno from 1988 through 1991.

In fact, it was the 1991 Gold race that best showcased the formidable partnership of man and machine. As soon as he heard the traditional call—“Gentlemen, you have a race!”—Shelton hammered down the chute and led the field around the first pylon. Riding his tail were Bill “Tiger” Destefani in the P-51 Strega and Skip Holm in Tsunami, the great coulda-shoulda-woulda scratch-built racer that never caught a break. Destefani and Holm dogged Shelton for 73 miles, but the Bear ran like a scalded ’cat, maintaining a winning gap the entire race. “That was the best race I’ve ever seen,” says Pete Law, a longtime Lockheed Skunk Works thermodynamicist who has provided engineering support for virtually every Unlimited winner at Reno since 1966. “It was the race of all races.” Lyle Shelton never won another Gold.

Chris Langham and Keith Geary are perched on ladders as they remove the Bear’s propeller. Unlike most other jobs on the Bearcat, this is relatively simple, requiring no special tools or expertise. But the propeller itself is a rare Douglas A-1 Skyraider unit featuring the latest hub with the earliest blades—so slender they’re referred to as toothpicks. “We treat it like an egg,” says Langham.

Langham, 42, volunteers when he’s not working as a mechanic for a shipping company. He gravitated to the airplane five years ago because it was so different from everything else he had worked on. “The longerons are spot-welded,” he says. “We don’t do that anymore. The elevator and rudder are made out of fabric. We have to search for months to find some parts. Worst-case scenario, we fab them ourselves. We make our own hoses. We do our own machining and welding. There are times when we work 20-hour days for seven or eight days. But like John Penney says: ‘She’s a seductive bitch.’ No matter what she does to you, you keep coming back.”

Hickle estimates that over the years, about 130 people have worked on Rare Bear. All but a handful have been volunteers, and about 90 percent of them have been airplane mechanics. At times, when sponsorship was paying the bills, as many as 30 people supported the Bear at Reno. This year, the crew will probably be a third that. And already, preparations are running behind schedule. Not because there isn’t enough manpower but because Cornell hasn’t been able to locate a small but essential component called a master rod bearing.

The good news is that Penney won’t need much time to get up to speed. He’s already flown the Bear to four Golds, and he’s intimately familiar with the airplane’s idiosyncrasies: the brain-scrambling noise, the Bear’s reduced stability at racing speeds, the effort required to manipulate the stick while arcing around the Reno pylons. “It’s hard, physical work,” he says. “The Bear is a fairly docile, well-mannered, nice-handling airplane in the benign flight regime. But at racing speed, it gets kind of hostile. Every time I climb into it, I treat it as a first flight in terms of how focused I am and how much attention I pay to every little detail.”

Rare Bear’s principal competition at Reno promises to be last year’s winner, Strega; this year the P-51 will be raced for the first time by 22-year-old Steve Hinton Jr. Next in the pecking order is the Sanders brothers’ Dreadnought, a Sea Fury that has won two Golds at Reno. For gamblers looking for a dark horse, there’s Czech Mate, a Yak-11. Six-time winner Dago Red won’t be racing this year. Ditto for 2006 champ September Fury. So the airplane to beat looks to be Race 77, as the Bear is known in Reno parlance.

“It’ll be Number One, no question,” says Pete Law. “With Dave Cornell back on board, it should be head and shoulders above anything that’s ever raced at Reno.”

The team’s goal for 2009 is Gold number 11. “We want to win soundly,” says Redick. Next, the three-kilometer record beckons; Cornell thinks 550 mph is a plausible number. And after that? “Everybody involved in this airplane, from the race team to the crew chief to the pilot to the owner, is doing it for the love of it,” says Rod Lewis. “So my goal is to continue to do it as long as it’s fun.”

Sounds like the Bear could be in business for another 40 years.

Preston Lerner wrote about U.S. Navy E-2 Hawkeyes in the June/July 2008 issue.