Pilots and Fans Dedicated to Prolonging the Stardom of the Beech 18

About 50 or less remain available for commercial use worldwide.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Beech-Boys-Main-631.jpg)

If Marilyn Monroe had been an airplane, she would have been a Beechcraft Model 18. With buxom radial engines and ample forked tail, the Beech 18 has not just the movie star’s curves, but, like her, an adoring fan club. Pilot and civil engineer Matt Walker is a member.

Walker, 58, owns four Beech 18s. His affair with the airplane started soon after he graduated from engineering school in 1980, when he began moonlighting on evenings and weekends flying Beech 18s on cargo runs in and out of Long Beach, California. “They’re kinetic art,” says Walker. “The airplane always draws a crowd wherever it goes.”

Of all the piston-powered airplanes manufactured in the United States, none has remained in continuous production longer. The Beech 18, also known as the Twin Beech, rolled out of the Beech Aircraft Company’s Wichita, Kansas assembly plant from 1937 to 1970. In all, 8,980 Model 18s were built, 5,186 of them during World War II as military transports and trainers.

Yet despite its vast numbers and long-standing popularity, no more than perhaps 50 remain in commercial use worldwide. Another 300 or so are believed to be held by private collectors, pampered hangar queens mostly, dusted off and flown only during airshows, if at all.

While time has taken its toll on those that remain in flying condition, the ardor of Twin Beech enthusiasts is hardly on the wane. Proof of the airplane’s popularity shows up on the Internet, where forums like beechtalk.com and beech18.net have supported a community of self-proclaimed “Beechnuts,” who swap everything from maintenance tips to photos of their favorite airplanes.

H.F. “Enrico” Bottieri, 87, is a longtime Beech 18 owner. During World War II, he trained as a P-47 Thunderbolt pilot but was never deployed overseas. He subsequently spent nearly 30 years as a TWA flight engineer and captain. Logging more than 25,000 hours in the air, he’s flown nearly 100 aircraft types. But it was not until the Beech 18 he has owned since 1975 was nearly destroyed in a bizarre incident that Bottieri learned just how much one old airplane can affect lives.

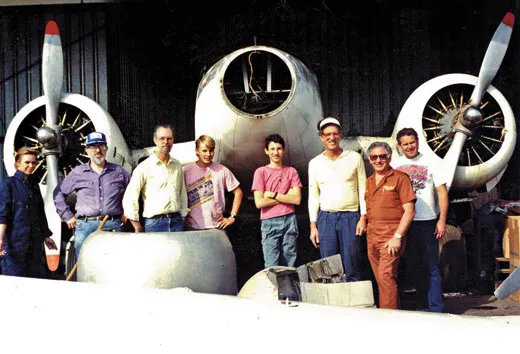

The motives remain muddled, but one day in 1985, an emotionally unstable airplane mechanic rammed his car at high speed into Bottieri’s Beech while it was parked on the ramp at his home airfield in warbird-friendly Chino, California. The damage was extensive: The wings were wrinkled, and the tail assembly was bent nearly 30 degrees. (The mechanic was uninjured and was arrested.) Even though Bottieri was at the time a licensed airframe-and-powerplant mechanic, he couldn’t do all the repair work himself. But something extraordinary occurred: When word of the assault on the airplane spread, volunteers began showing up, offering to help fix it.

Most were not aviators, and few had any experience in aircraft restoration. Yet every Saturday, rain or shine, and sometimes Sundays too, they would meet for a cookout and spend the day in Bottieri’s hangar, slowly piecing the Twin Beech back together. For many, says Bottieri, the experience “was almost like going to church.” Whatever problems they endured in their lives away from the airfield—meddlesome bosses, bad marriages, health issues—were put aside as they focused on repairing the vintage aircraft. In all, more than 200 people pitched in for 16 years to restore the Beech 18 to airworthiness.

One of them, Stephen Törnblom, 35, was not yet in his teens when he began persuading his father to drive him every Saturday to Bottieri’s hangar. While laboring over the damaged aircraft, Törnblom says, he learned how to see a task through to completion. He also learned how to grill a mean hamburger. “I was the one who barbequed,” says Törnblom, who works today in Long Beach as an operations coordinator for JetBlue.

After his army finished restoring the airplane, Bottieri christened it Impossible Dream. He wears its likeness on the back of his leather flight jacket, along with the embroidered words “Beech Boys,” the name of the association he helped found to carry on the legacy of the Model 18. Bottieri had quadruple bypass surgery in July 2011, but that hasn’t stopped him from flying Impossible Dream (he is accompanied by another pilot).

Bottieri recites an expression often repeated by Model 18 lovers: “There are many Beech twins,” he says, eyes twinkling, “but only one Twin Beech.”

***

The AT-7 Navigator, AT-11 Kansan, C-45 Expeditor. The Bug Smasher. The Exploder. The Slow Navy Bomber. The Wichita Ice Maker. The Wichita Wiggler. All were Beech 18s. Over the years, 32 variants, both military and civilian, were manufactured. Federal aviation officials approved more than 200 changes to the original design, including aerodynamic and structural improvements to the wings, engines, and landing gear. One modification, to the fuselage, was purportedly ordered by Olive Ann, the wife of company founder Walter Herschel Beech.

As the story goes, the self-made aircraft mogul was riding to New York in a Model 18 along with Olive Ann and a few of her friends when he excused himself to visit the small toilet compartment at the rear of the cabin. Upon finishing his business, Beech, a large man, realized that, because of his airplane’s tapering roofline, he didn’t have room to hike his pants up.

The door to the restroom flung open. A frustrated Beech stepped out and, in plain view of Olive Ann’s friends, squared himself away. Olive Ann was not pleased. Soon after landing, she reportedly instructed company engineers to make sure a similar episode never happened again. Their solution was to blow out the top of the fuselage and build in another six inches of headroom.

Some aviation historians believe that Walter Beech copied Lockheed’s similar-looking Model 12 Electra Junior: an all-metal, twin-radial-engine craft that could comfortably transport a half-dozen executives for more than 800 miles at nearly 200 mph. Ferrying well-heeled businessmen between sales calls and board meetings, however, was only part of the Beech 18’s job. From Argentina to Zaire and virtually everywhere in between, Model 18s evacuated the sick and injured as air ambulances, delivered the mail, dropped parachutists, ran guns and narcotics, seeded clouds, sprayed insects, and sowed good bugs to eat the bad ones. They fought fires, conducted photo-reconnaissance, and towed advertising banners. Equipped with pontoons or skis, Beech 18s became bushplanes. Flown by famed stunt pilots like Frank Tallman, they appeared in memorable Hollywood films (It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World; Octopussy) and a few less than memorable ones (Nicolas Cage’s Con Air; Vin Diesel’s xXx).

The Twin Beech was also a prodigious freighter. Crates of canceled checks, drums of frozen buffalo meat, automobile parts, oil-drilling equipment—you name it, pilots say, and the Beech 18, often overloaded, probably flew it. Alec S. Hamilton, an American Airlines DC-10 captain who flew Beech 18s while hauling copies of the Wall Street Journal between northern California and Salt Lake City, remembers one flight during the early 1970s in which he transported cargo that ordinarily would have flown on its own.

Hamilton was dispatched to Guaymas, Mexico, to pick up a shipment of African Grey parrots. The birds screeched like crazy as they were loaded aboard. “As soon as I started the engines,” says Hamilton, “they never made another sound.” Perhaps the parrots grew mesmerized by the harmonic “music” that pilots say the Twin Beech engines croon when balanced and in tune—a soothing Zen-like hum, far removed from the impersonal whine of a 21st century jet turbine.

To command the surprisingly agile Twin Beech, as I did briefly from the right seat of one owned by Matt Walker, cruising low over the Inland Empire east of Los Angeles, is to be transported not only in time, but also in mindset. In an era of function over form, the Beech 18 serves as a reminder that there is still value in unhurried elegance.

“Every time I [fly in a Beech 18], I feel like I’m going first class,” says retired Air Force mechanic Paul Minert, who became a Twin Beech fan while helping restore Bottieri’s Impossible Dream.

Traveling first class, of course, doesn’t come cheap. Just ask Blane Grow, an anesthesiologist from Paducah, Kentucky, who has owned his circa-1946 Twin Beech for 25 years. Outfitted with long-range fuel tanks that allow it to stay aloft for as long as 13 hours, the airplane had been used by drug runners before being confiscated by federal authorities and left to rot under the south Florida sun. Grow installed new engines and revamped the instrument panel. The work, among other repairs and improvements, cost him a small fortune. But it’s been the increasing cost of fuel that has him wondering about the airplane’s affordability.

“It’s gotten painful to fill up,” he says. Cruising, the Beech 18 uses about 40 gallons an hour, while climbing can consume significantly more fuel. The dual engines on Grow’s Beech have been altered to burn unleaded automobile gas, which these days costs about $2 less per gallon than the low-lead fuel used by most piston-driven aircraft. Even with the modification, flying the airplane can hardly be considered inexpensive. But Grow has no immediate plans to part with it, if for no other reason than his desire to help young people, who are typically more enamored of what he describes as “cyberthings,” better understand the value of such non-cyber treasures as the Twin Beech.

“As long as I can,” he says, “I plan to nurture, preserve, and operate mine as a tribute to a time when individuals were more bold.”

***

Remember Field of Dreams? The ghost of star outfielder Shoeless Joe Jackson, played by actor Ray Liotta, gazes at the baseball field that farmer Kevin Costner has hewn from a stand of Midwestern corn and asks, “Is this heaven?”

“No,” Costner replies. “It’s Iowa.”

No question a similar scene could play out between any number of Model 18 enthusiasts and Taigh Ramey, whose company, Vintage Aircraft, specializes in restoring the airplanes. Only heaven in this case isn’t Iowa. It’s near the north end of California’s San Joaquin Valley, at the drowsy Stockton Metropolitan Airport.

There, tucked behind the control tower in a corrugated-metal hangar that bakes in summer and can get downright nippy come winter, is a veritable Fibber McGee’s closet crammed with every piece and part that could have any possible use on a Twin Beech: four partially assembled airframes, antiquated flight instruments, engine and airframe components, and shelf upon shelf, box upon box, of fittings, fasteners, and other thingamabobs. When no serviceable replacements can be located, some parts are machined on the premises. Much of the rest Ramey hunts down on Web sites like eBay.

“Fortunately,” he says, “we’re a nation of collectors.”

Ramey’s ode to all things Twin Beech continues outside his hangar. Nuzzled like submarines around a tender are six Beech 18s in various states of renovation or, depending on your point of view, decomposition. Parked alongside them is his latest project, a Lockheed-built, U.S. Navy PV-2D Harpoon, circa 1945.

Ramey has owned about a dozen Beech 18s, and says that since starting Vintage Aircraft more than 20 years ago, he’s restored and maintained probably five times that many. Owners from as far away as Australia and Switzerland have ventured to Stockton seeking his advice and services.

Flight students pay upward of $600 an hour (fuel and aircraft rental included), hoping to learn the skills necessary to master an airplane that, unless it’s directed properly, can sometimes prove, like Marilyn Monroe, difficult. Like most taildraggers, the Beech 18, upon landing, is predisposed to ground loop if an aviator is not on his game. In the Twin Beech, the inclination to swap ends can occur with unnerving rapidity.

Some pilots, like John Hannigan, never do get a true feel for the airplane. Hannigan was in his early 70s, a retired mechanical engineer with end-stage prostate cancer, when he first approached Ramey about helping him acquire a B-25 Mitchell bomber. “When he found how expensive the B-25 is to operate,” says Ramey, “he decided, ‘Oh, maybe not.’ ”

With Ramey’s guidance, Hannigan opted for a Twin Beech. Ramey found one for him in good condition in Rialto, California, its aluminum skin still trimmed in bright lime-green paint, denoting its former life as a U.S. Air Force instrument-training aircraft. Then he hired Ramey to teach him to fly it.

“John tried to kill me in more ways than all my other students combined,” Ramey says, smiling. “It was a learning experience for both of us.”

Hannigan sometimes confused the fuel-air mixture and throttle controls, starving the engines of gas at particularly inopportune times—like right after takeoff. On occasion, he had trouble with directional control. Once, during an especially windy takeoff at Stockton, the airplane went crosswise and Ramey had to take over, jamming the rudder pedals so forcefully to stop from veering out of control that he snapped a rudder cable.

Hannigan logged about 200 hours in his Beech 18 with Ramey riding right seat. They became close friends. They even flew together to one of the annual AirVenture fly-ins at Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Ramey came to respect and admire Hannigan’s pluck, but says he never felt confident enough in his student’s skills to let him fly solo. Hannigan never seemed to mind. Before he died in 2007, he willed the aircraft to Ramey. It still bears Hannigan’s name, stenciled in faded black, just below the pilot’s window.

Ramey’s fascination with the Beech 18 began in 1981, when he was a freshman studying aeronautics at San Jose State University. It was Christmas time. Rubik’s Cube was a big gift that year, but Ramey’s dad, Henry, had other ideas. He bought his son a World War II-era gun turret. On its canvas cover was printed “Training Type A-8 for Model AT-11 Aircraft.”

“My first thought was Cool! My very own gun turret,” recalls Ramey. “My second thought was What the heck is an AT-11?”

It’s a Beech 18, in military uniform.

He learned all he could about the airplane. Later, he would discover that his father, an Army Air Forces navigator and veteran of the Pacific campaign, was part of an AT-11 crew that had buzzed a control tower on Japanese-held Rota in the Mariana Islands, prompting the lookouts to leap for their lives.

Ramey was hooked.

He was determined to find an AT-11 to accommodate his fully functioning .30-caliber gun turret. As it turned out, San Jose State owned two non-flying Beech 18s, which had been used to train would-be airplane mechanics. One of the airplanes, he determined upon close inspection, had served as a wartime AT-11. Ramey bought it for $250. He had to borrow the cash from his mother.

“And that,” he says, surveying the repository of history that is his hangar, “is how all this madness started.”

Vintage Aircraft has since grown to employ an office manager and five full-time mechanics, including Rick Clausen, 55, a former computer network administrator who is also a pilot with DC-3 experience. After being laid off 10 years ago from his corporate job, Clausen chanced to meet Ramey at a gathering of warbird enthusiasts, and asked if he had any openings. Ramey eventually called.

“He said, ‘I’ve gotta change a fuel pump real quick. Any interest?’ ” remembers Clausen. “I was down here in 20 minutes and never left.”

Clausen earns a third of what he made managing computer systems, but says that working on Beech 18s all day comes with its own rewards. “It’s so funky, it’s not even retro,” says Clausen. “For all those digital folks out there, it’s completely and totally analog.”

Pulleys and cables. Flight instruments that could have been designed by Jules Verne. An autopilot? Dream on. In an age of shiny glass cockpits and fly-by-wire controls, many who own a Beech 18, including Roscoe Diehl, a former Lockheed F-104 test pilot and retired Delta Air Lines captain, would have it no other way. “This is a plane you fly from the minute you pull chocks to the minute you put ’em back under the wheels,” says Diehl. “It’s definitely a challenge.”

Revered as it is, the Twin Beech comes with the kind of complications common among its contemporaries: Serviceable parts are becoming more elusive. The nation’s biggest supplier of Beech 18 components, Oklahoma-based Southwestern Aero Exchange, shut down operations when its owner died in 2006 and is liquidating its inventory. Then there is the advancing age of many of its most ardent devotees, who were born before the Twin Beech was on the drawing board. When asked what will be the airplane’s legacy when they are all gone, some shrug their shoulders stoically.

“An antique toy without any real function” is how Diehl envisions what will become of the Beech 18—the inevitable fate of most machinery trumped by technology’s relentless march.

Ramey professes little concern over the aircraft’s future. Work orders at his shop remain steady, he reports. “We are all just caretakers of these treasures,” he says. “If we do our jobs right, the aircraft will live for many future generations to enjoy long after we are gone and forgotten.”

Matt Walker is too preoccupied to ponder such thoughts just now. He’s prepping his favorite Beech 18 for flight. N1828D was once owned by the company that made Lay’s potato chips. Walker found it in 1992, sitting all but abandoned at a parachute drop zone outside Kapowsin, Washington. The airplane had not been flown in 11 years, and owls had converted the fuselage into condos. Walker spent 18 months restoring the airplane to airworthiness. He used to take skydivers up in it. Now he mostly flies it for pleasure, and to wing him and his wife between their homes in Henderson, Nevada, and southern California.

As spectators gather on the ramp at Chino, Walker energizes the right boost pump, cracks the throttle, and sets the friction lock. Then he simultaneously thumbs the primer and starter buttons, keeping a close eye on fuel, oil, and temperature gauges.

“C’mon, baby,” he coaxes the hulking 450-horsepower Pratt & Whitney right engine. Then he starts up the left. The Twin Beech’s powerplants protest at first, coughing and sputtering like old men roused from sleep, before roaring to life, a defiant shout at history.

David Freed is a pilot, novelist, and former Los Angeles Times reporter. His latest mystery-thriller, Fangs Out, will be released in May.