The Big Race of 1910

How the first U.S. air race launched an aviation tradition.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/12C_DJ10-flash.jpg)

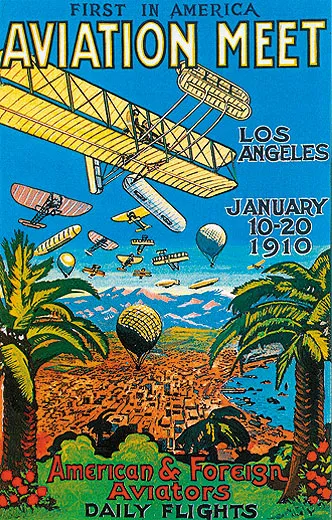

When Glenn Curtiss edged Frenchman Louis Blériot at the world's first air race, in Reims, France, in August 1909, few Americans had seen an airplane, let alone an air race. Curtiss won them the opportunity. By bringing home air racing's first important award—the Gordon Bennett Trophy—Curtiss also won the right for his country to host the next international air meet. And thus America got its first air race, held in the city of Los Angeles 100 years ago.

In October 1909, airship pilot Roy Knabenshue, from Toledo, Ohio, and Charles Willard, the first man Curtiss taught to fly, met and decided to use southern California as a winter base for their aerial demonstrations. They contacted Curtiss, thinking his fame would help draw crowds as big as those that attended the event in Reims. Curtiss agreed to the plan, though he had no intention of using the venue to defend the trophy; that race would be months away and held in New York, where he believed more money was to be made than in California. Knabenshue contacted Los Angeles promoter Dick Ferris, who in turn, got the Los Angeles Merchants and Manufacturers Association on board for financial support, and persuaded railroad magnate Henry Huntington to pledge $50,000. (For Huntington it was a no-brainer; his trains, after all, would haul spectators to the meet.)

"No one knew who would come," says Judson Grenier, a history professor retired from California State University at Dominguez Hills. "But there was a great economic optimism, with the city bringing in water [by funding a $23 million aqueduct] and getting a port [by annexing nearby San Pedro], both in August 1909. So the feeling was: If we can do that, we can do anything."

One of the first to see economic opportunity in air racing was newspaper owner William Randolph Hearst, who flogged the event in his Los Angeles Examiner, one of the city's four daily newspapers. Hearst, who had traveled down from San Francisco, arranged for a hot-air balloon to be tethered on the grounds during the meet. On the balloon's side were the words "It's all in the Examiner." And it was, including fashion tips for women spectators.

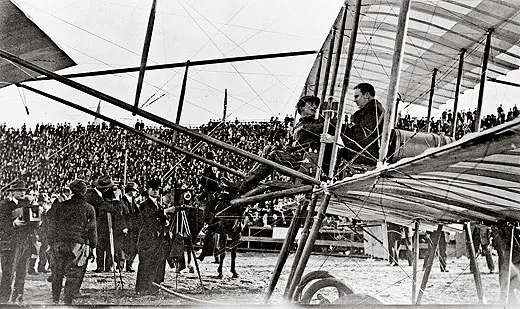

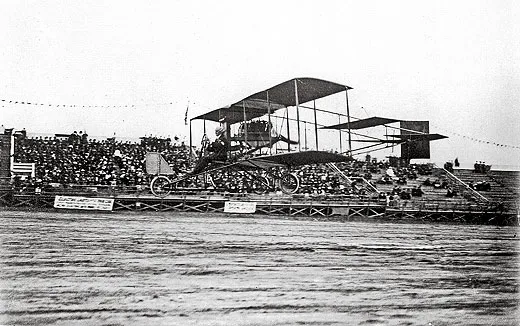

The races—along with demonstrations—took place at Dominguez Field, just south of Los Angeles, on land loaned by the family of Manuel Dominguez, from January 10 to 20. Workers had erected a grandstand capable of seating 26,000, and pitched large tents for the pilots to store and work on their airplanes. The advertised prize money was $70,000. Much of it was for specific tasks, such as $10,000 for a nonstop balloon flight to the Atlantic coast, which went unawarded. More realistic were the prizes for breaking major world records, although many of those too were never claimed. But all helped achieve the goal of bringing together some of the most skilled and daring pilots in the United States.

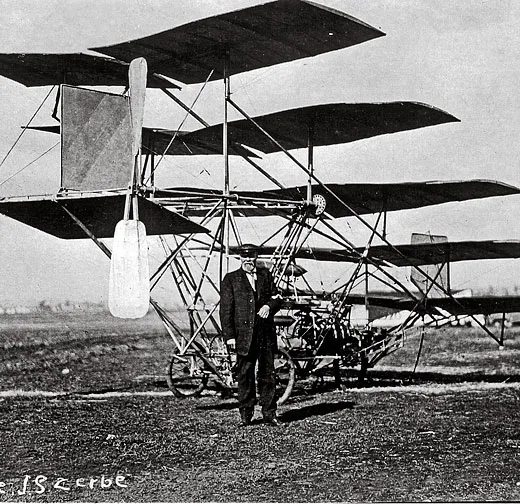

Skilled and daring pilots were not plentiful in 1910 America. Although 43 flying machines were officially entered, only 16 showed up, and not all of them flew. One five-wing "multi-plane" built by a local high school teacher, for example, participated only as a static display; it couldn't get off the ground.

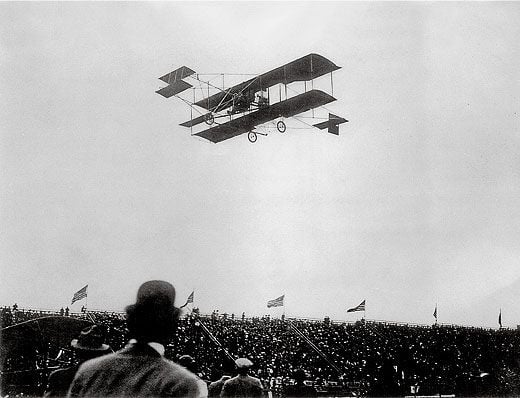

Despite the nearly empty skies, the meet caused a sensation in Los Angeles. Fans clambered aboard Huntington's streetcars, which left the city for the field every two minutes. More than 20,000 packed the stands each day. To draw out-of-towners, the meet's executive committee, of which Ferris was a member, had cleverly arranged for each day to honor a different city: "San Diego Day," "San Francisco Day," and so on. Schools in the honored districts were closed on those days, so when it was Los Angeles' turn, a 13-year-old named Jimmy Doolittle (who himself became a famous race pilot, before gaining even more fame for leading a World War II bombing raid on Tokyo) got to see his first airplane.

"The city was turned on," says Grenier. "I don't think any other event has had that kind of effect of shutting down the city for two weeks. You had businesses closing, schools letting out, women's groups coming in en masse. Anybody who could walk, and some who couldn't, made it to the meet. Cars were pretty primitive then, with canvas tops, so only a very small number of people came in cars. Most of them rode the train, then walked the half-mile to the field. It was kind of the climax of boosterism that's so characteristic of Los Angeles."

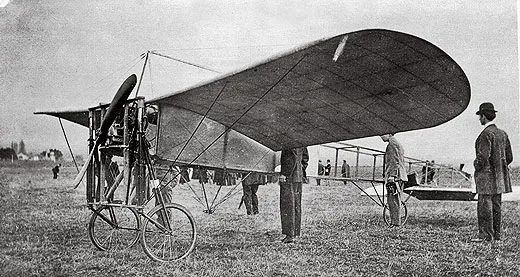

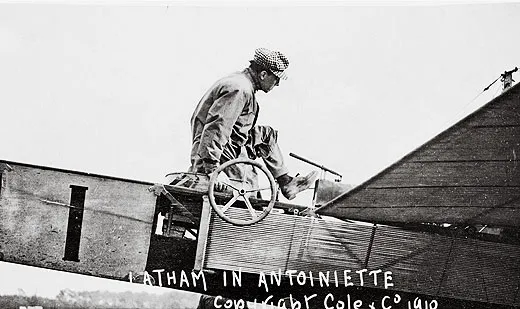

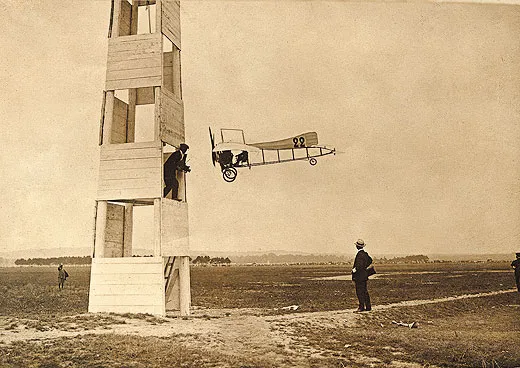

The star of the show was a charismatic Frenchman, Louis Paulhan, who had brought two Farman biplanes and two Blériot monoplanes and was guaranteed $25,000 to appear. Described in newspapers as "the wonderful little Frenchman," he had worked in a military balloon factory and taught himself to fly airplanes. Paulhan's appearance qualified the meet as "international," and he set new world records for endurance and altitude. He took to the air at the slightest encouragement, often appearing to plan his flight as he went along. Paulhan's 45-mile round trip between the field and the Santa Anita racetrack brought thousands of people to rooftops and farm fields in hopes of seeing the fearless aviator.

Curtiss, who was the first in the air over Dominguez Field in his Reims racer, was not bothered by all the applause for Paulhan, according to C.R. Rosenberry's book Glenn Curtiss: Pioneer of Flight. "I am satisfied to let Paulhan have the applause, providing I am able to take the prizes," he was quoted as telling a colleague.

Curtiss may have feigned indifference, but he was under enormous pressure at the time, says Ken Pauley, a retired aerospace engineer in San Pedro who has produced a photo book about the meet in conjunction with the centennial. "He was due in court in New York the next month to answer the Wright brothers' lawsuit [over patent infringement]. The Wrights had clamped down lawsuits against both Curtiss and Paulhan." Curtiss, in fact, used the meet to try to gather witnesses to bolster his defense. He "seized every opportunity, when the field was free from program events, for demonstrations calculated to disprove the claim of the Wrights that the control of his machines, like theirs, depended on a combination of the rear vertical rudder with the action of the ailerons," Rosenberry wrote.

Although the Wrights did not accept an invitation to attend the meet, they were kept well informed about it. Before it was over, Wilbur Wright had cabled Roy Knabenshue, asking him to come to Dayton, Ohio, to discuss managing a flying team (see "Ladies and Gentlemen, The Aeroplane!," Apr./May 2008); by mid-March, Knabenshue was on the payroll.

"The meet really had a tremendous impact on how people thought about transportation," says Pauley, who worked on the Apollo heat shield for North American Rockwell. "Aviation was something new for them and no longer a joke or a fantasy. I remember my grandfather's skepticism about going to the moon. It was the same thing here with the airplane."

Air racing today generally involves similar airplanes forming up and tearing wingtip to wingtip around pylons. In 1910, such behavior was simply unheard of. The most popular challenge then was to set the fastest time for a single lap around a six-pylon, 1.6-mile course. Four pilots, flying one at a time, made at least one attempt at that at Dominguez Field, with Curtiss making five separate laps on four days. His fastest speed was 43.9 mph, nearly as fast as his winning speed at Reims, where the course was much longer and thus enabled higher speeds (Curtiss had won the Gordon Bennett Trophy with a speed of 46.5 mph). His nearest rival was Paulhan, almost nine seconds slower. The only other airplane race to attract more than one pilot was a 10-lap circuit, which Curtiss also won over Paulhan.

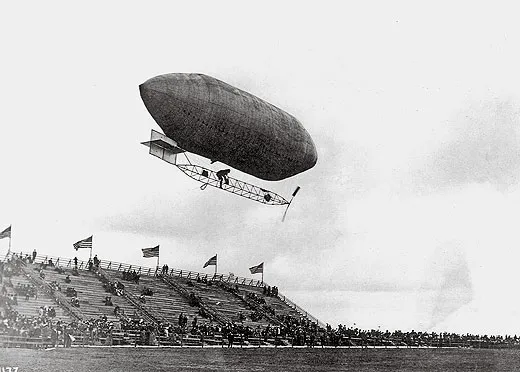

Curtiss again was crowned the "king of speed" after a wind-aided dash in front of the crowd at an estimated 60 mph. But his was a solo run. What brought the crowd to its feet was a head-to-head dirigible race around the oval by Knabenshue and Lincoln Beachey. It was the most exciting air race yet seen—even though both were chugging along at less than 20 mph. Beachey, who won by a few seconds, sensed the end of the airship era at Dominguez Field and "wondered how long his dirigible career would last," wrote Frank Marrero in Lincoln Beachey: The Man Who Owned the Sky. Beachey went on to become one of America's greatest acrobatic airplane pilots and the first to fly a loop.

A wealthy Seattle timber man named William Boeing was so impressed that he asked nearly every pilot to take him up for a ride. Only Paulhan agreed. The 28-year-old Boeing waited three days, but discovered on the fourth that the Frenchman had left the meet. (Four years later, a friend gave Boeing his first ride, in a Curtiss hydroplane that he found noisy, unstable, and terribly uncomfortable. He decided he could build a better airplane.)

Though Paulhan was slower than Curtiss, he won more in prize money—$19,000 to Curtiss' $6,000. More than 200,000 people had turned out over the 11 days, and gate receipts were $137,520, against expenses of $115,000. (The Gordon Bennett Trophy race wouldn't be held until the year's last big air meet, at Belmont Park, Long Island, New York, from October 22 to 31; cold winds kept all but a few thousand people from attending.)

Today, there's little left of what the Los Angeles Times in 1910 called "one of the greatest public events in the history of the West." Where the hilltop grandstand once stood is now a five-million-square-foot warehouse complex called the Dominguez Technology Center. Tenants include aerospace firms TRW and Northrop Grumman, and streets around the center are named after the pilots who flew in the meet. The nearby Dominguez Rancho Adobe Museum is planning displays, lectures, and other activities throughout 2010 to mark the race centennial.

The biggest legacy may be the continuing presence in southern California of the aerospace industry—the state's biggest employer. From Lockheed Martin's Skunk Works in Los Angeles to Boeing's sprawling space system offices in Huntington Beach (named for L.A.'s railroad king), the leading aerospace companies help prime the nation's economic pump near the city that welcomed America's first air race.

Don Berliner is a writer in Alexandria, Virginia.