The Birthplaces of Aviation

It didn’t all happen at Kitty Hawk.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Arch_Invent_Flash_AUG09.jpg)

In the story of the airplane’s invention, there are more characters than just the Wright brothers. And more settings too: In the first decade after the Wrights’ landmark 1903 flight, airplanes were being invented in countries far beyond America and the other two hotspots of early aviation: France and England.

Many of the aircraft included here were the first to fly in their countries. Though big news locally, word of their success traveled very slowly. The 1912 edition of Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft says, regarding Chile’s efforts in aviation, “There are vague rumors of machines building in Chili [sic], but so far as can be discovered, none have got beyond the model stage.” Though that was technically true, a Chilean named José Luis Sanchez-Besa, living in France, was building both land- and seaplanes.

Many of the aircraft builders in this story clearly got ideas from fellow inventors; a few of these designs are close duplicates of successful forebears. But other inventors appear to have worked in isolation, largely unaware of other airplanes springing to life around the world. Besides the Wrights’ crisp, sensible designs, the world began seeing airplanes with more exotic or eccentric appearances—and some could even fly.

Romania

Though Trajan Vuia earned a doctorate in law in 1901, between scholastic assignments he sketched airplane designs. He moved to Paris to join what he considered the hub of the aviation community, and in February 1903 he offered a design to the Committee of Aeronautics of the Science Academy. The committee, adhering to the prevailing wisdom that the best design would be a double-prop biplane, rejected his single-propeller monoplane as a dream.

Still, that August, Vuia licensed his airframe design in France, and the next year licensed another design incorporating his 20-horsepower engine in Great Britain. He completed the full machine by December 1905.

That month, outside Paris and beyond the view of journalists, Vuia began maneuvering the body of his vehicle as a car; later he added wings and practiced faster taxiing.

While the first officially observed airplane flight in Europe was made by Brazilian Alberto Santos Dumont in Paris on October 23, 1906, according to some reports, on March 18 of that year, Vuia rolled the Trajan Vuia 1 for 150 feet, lifted three feet above the dirt, and flew for 36 feet. Then his engine quit. Vuia is reported to have flown again in June, July, and August.

Germany

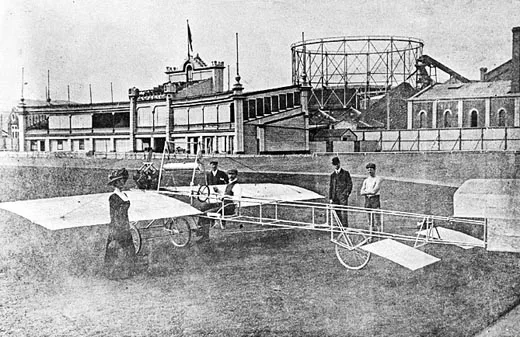

Like the Wright brothers, Hans Grade was schooled in the mechanics of two-wheel vehicles. He built his first motorcycle in 1903, and in 1905 founded a shop in Magdeburg, Germany, where he tinkered simultaneously with aircraft design and motorcycles.

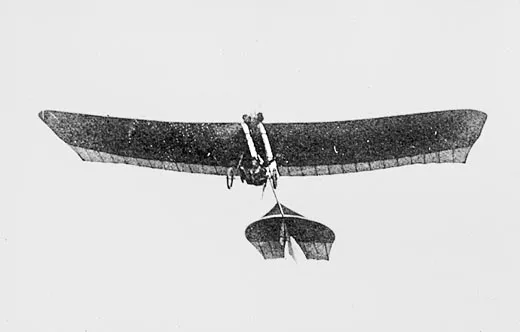

By 1907 he had finalized a concept for a triplane. On October 28, 1908, his aircraft flew 24 feet. The following August, his monoplane, named Libelle (dragonfly) and based on Santos Dumont’s Demoiselle—began hops from Borkheide.

In October 1909, Grade won 40,000 marks in a competition seeking the first German airplane with a German engine to complete a figure eight of three kilometers. Within a month, he could fly Libelle nonstop for 55 minutes, seated in chariot position and warping the wings by grasping overhead wires.

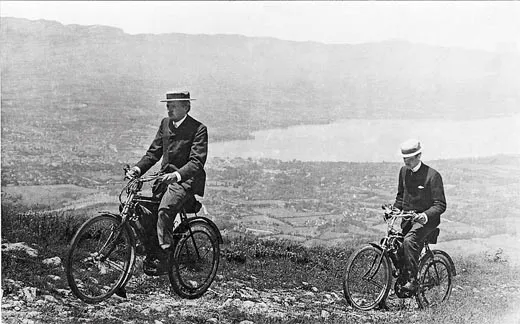

Switzerland

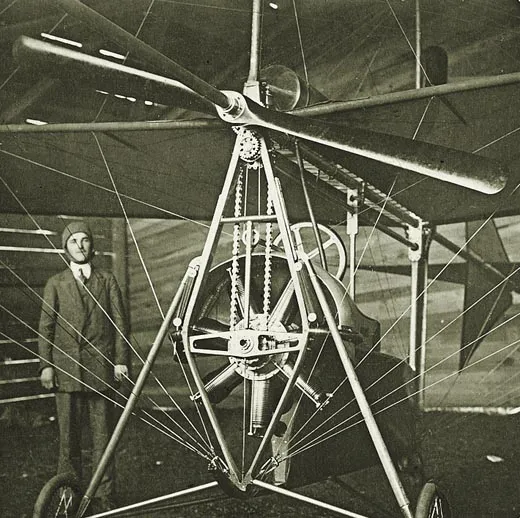

Defying the overall storyline of aviation history, Armand and Henri Dufaux first gained fame as helicopter designers, delivering partially working models and running engine demonstrations as early as May 1905. Only then did they turn to fixed-wing design. The brothers’ first prototype, the Dufaux 1, was shown off in Geneva and Paris, and led to a series of designs culminating in a 1908 triplane, which was to function as a tilt-rotor, with an engine that could pivot to provide either vertical or horizontal thrust. Brilliantly advanced, it never left the ground.

Belgium

Taking great liberties in designing his biplane in 1909, Baron Pierre de Caters studied the type III airplane of French designer Henri Farman and copied nearly every pulley and screw.

The following year, de Caters devised a sturdier monoplane with a front-mounted, 100-horsepower Argus engine and a 45-foot wingspan. The aircraft required quite a bit of muscle to fly. The baron grunted through turns he executed via wing warp pulleys anchored to the wheel struts, and a rudder bar responded to stomps of his foot.

Ireland

In another example of aero-appropriation, Harry George Ferguson and Joe, his brother and partner in an automotive garage, would visit air exhibitions in France and England and take careful measurements of the parked aircraft. Throughout 1909 Harry fashioned his own airplane with 26-foot wings, pairing it with an air-cooled 35-hp engine by J.A. Prestwich. At Hillsborough Park in Belfast on New Year’s Eve 1909, Ferguson’s 32-foot monoplane achieved a maximum altitude of 12 feet; it stayed aloft for some 400 feet. The Belfast Telegraph reported: “The roar of the eight cylinders was like the sound of a Gatling gun in action. The machine was set against the wind, [and] the splendid pull of the new propeller swept the big aeroplane along as Mr. Ferguson advanced the lever…. Although fierce gusts of wind made the machine wobble a little, twice the navigator steadied her by bringing her head to wind, the first successful initial flight that has ever been attempted upon an aeroplane.” Well, the first in Ireland, anyway.

Hungary

Two of the world’s earliest journals devoted exclusively to aviation, Aero News and the professional journal Aeronaut, served as inspiration for young readers and would-be designers Janos Adorjan and F. Dedics. The two jointly designed a 25-hp, two-cylinder engine, which was built by the Köhler Brothers factory to power an elegant design named the Strucc (Ostrich). At 617 pounds, the Strucc had a wingspan of 26 feet, three inches, and was 24 feet long. In the Second International Air Race, held in June 1910, Adorjan became the first Hungarian to fly in his country in his own design. There were 29 competitors; the Strucc came in third.

New Zealand

Who made the first flight in New Zealand? Herbert J. Pither swore to journalists that he did, on July 5, 1910, at remote Oreti Beach, with no witnesses present. Yet Rosemarie Smith, who spent years researching Pither for the Croydon Aviation Heritage Trust, said Pither never repeated his original statement, and late in life—by which time the legend had grown to include multiple flights at lofty heights—he denied it altogether.

We do know that Pither was a bicycle-frame maker with a shop specializing in boat engines, so he had expertise in both framing and propulsion to use in constructing an airplane. He produced a variant of a design by Frenchman Louis Blériot, making a frame of steel tube and wooden ribs and covering it with fabric. The pilot would control yaw with a tail rudder connected to a foot pedal, achieve lateral stability by warping the trailing edges of the wings with a steering wheel, and control the craft vertically by raising or lowering the elevator with a lever. Pither fitted bicycle wheels with shock absorbers to the undercarriage, and powered the craft with a four-cylinder, 40-hp engine.

Whether Pither actually flew or not, says Smith, after 1910 he never again designed an aircraft.

Poland

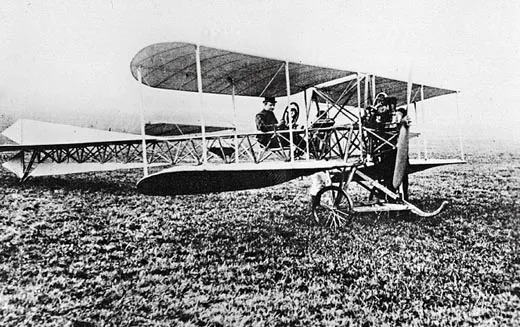

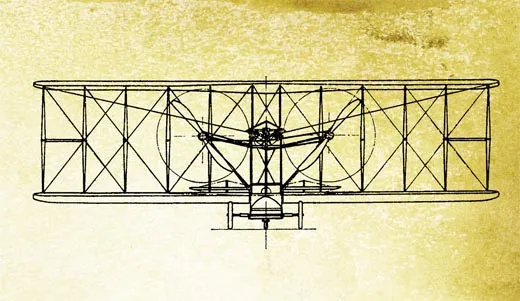

Flying called to Stefan Kozlowski, who left auto mechanics in 1909 to enroll in a German flight school. After earning his pilot’s certificate, he designed his own machine, a biplane with dual powerplants in a tractor configuration. The wings were inspired by the rectangular, rounded-tip wing structure of a Blériot XI.

Advised by a Czech engineer named Skopik, Kozlowski bought parts from France and Germany to assemble in a Warsaw lumberyard. His biplane was powered by a six-cylinder, 60-hp Anzani engine. During flight tests Kozlowski snapped the chain drives for the two tractor airscrews, so he replaced them with ropes leading from the engine shaft and then crossing, in the style of Wright biplanes, to counter-rotate the wood props. Kozlowski discovered that the Blériot-style wing struts were not rigid enough to cut vibration, so he replaced the pine with ash, and adjusted the position of the engine.

His design was spare and elegant, with no vertical stabilizer but with elevons on the wing, which could tilt one at a time for directional control normally provided by the tail. Maneuvered in opposite directions from each other, the elevons acted as ailerons for banking. When moved up to 60 degrees in concert, they functioned as air brakes.

In June 1910, Kozlowski made six flights: He never rose more than 10 feet, but he got up to 100 feet in distance.

Finding the machine tail-heavy, he planned to add vertical and horizontal stabilizers. But in a flight test, the wing hit a dirt mound, leaving Kozlowski with minor cuts and bruises and his machine a wreck. His investors refused to pay for repairs, and by the autumn of 1910 they had stripped his machine of all salable parts. Understandably, Kozlowski retired from airplane building.

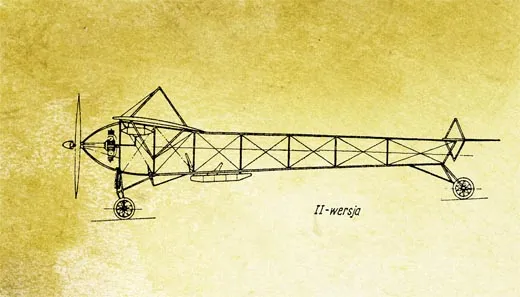

Another Pole, Henryk Brzeski, an engineer working in Vienna, devised an ingenious rotary engine; at the same time, in Krakow, Poland, the Schindler brothers—Wincenty, a mechanic, and Rudolf, an entrepreneurial inventor—built a scale model for a three-seat, high-wing monoplane, the Aquila (Falcon). In October 1909 they sent it into flight.

Bolstered by the small-scale success, the brothers tried a full-size machine, comparable to the Kozlowski design in that it lacked vertical tail surfaces, and the Schindlers teamed with Brzeski to begin work in Vienna. The Aquila’s triangle-shaped bamboo frame had been braced by wire, and flight would be controlled by linking the wing- and tail-warping mechanisms to an inclined steering wheel. The aircraft would be powered by

Brzeski’s revolutionary 50-hp rotary powerplant, which he called Iskra (Spark).

In its first attempt, the Aquila shuddered aloft, and after 50 feet crashed into a hedge. The crash was blamed on the Schindler airframe, and the aircraft’s development was scrapped.

Romania

Born in the province of Transylvania, Aurel Vlaicu built a flyable glider model at Munich Polytechnic in 1907. Two years later, he built a glider in which he carried one of the first females to fly: his eight-year-old sister, Valeria. After an exhibit of Vlaicu’s scale models in Bucharest, the Romanian war minister funded a workshop and staff at the Army Arsenal for Vlaicu to continue his work.

Vlaicu traveled to the Paris workshop of fellow Romanian Trajan Vuia to buy a 50-hp Gnome engine. By June 1910 he had produced Vlaicu 1, taking flight from Romania’s Cotroceni military airfield. Vlaicu called his design a “flying machine with an arrow-like fuselage.” The aircraft had a diamond-shape cockpit that hung like a pendulum beneath the fir wing spars. It had a hinged front elevator and rudders that moved in tandem. There were propellers in both the front and rear, and a fixed rear horizontal tail with two vertical control surfaces straddling the central aluminum tube, an arrangement that ensured stability and smooth turns.

By mid-August 1910 Vlaicu could make sharp turns and exceed an altitude of 450 feet, and one of his flights surpassed nine miles. Within six weeks, in a test of army reconnaissance, he had risen above 1,500 feet, winning a prize from Romanian Prince Ferdinand that funded the launch of his Vlaicu 2 the following February. This aircraft was a monoplane of a parasol design, with fabric on just the top of the wings and tail and without ribs— features that made the aircraft light and nimble.

Chile

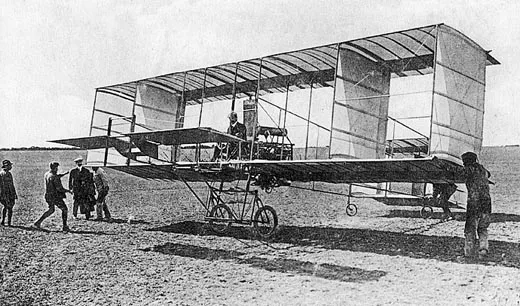

Another designer who borrowed liberally from fellow aircraft designers, José Luis Sanchez-Besa copied the Wrights’ pusher propulsion and the Voisin brothers’ designs. His 1910 biplane was full of curves, with a front elevator and a 50-hp Anzani chain-drive engine linked to two pusher props. He created a number of successful aircraft, for both land- and sea-based operations.

His 1912-1913 seaplane wrapped the pilot in a virtual tub, yet a land-based version was aerodynamic enough to work. Perhaps his most ambitious design had a Venetian-blind-like configuration of airfoils: five rows of 21 horizontal surfaces each.

Canada

William Wallace Gibson made his money in mining, and in 1906 he began to invest in manufacturing engines. However, Gibson’s propulsion efforts were marred. His four-cylinder engine shook itself to an early death. He had slightly better luck with a six-cylinder design, which in early 1910 yielded a smooth 60 hp. Next Gibson turned to an airframe. He sewed two 20-foot wings of silk staggered front and rear, and for pilot control used wires to tether a front elevator to his shoulder harness. On September 8, 1910, at a farm in Victoria, British Columbia, he managed to fly his 700-pound Twinplane 25 feet.

His second flight, on September 24, lasted 200 feet before a crosswind slammed him into an oak, crushing all but his engine and his spirit. By mid-1911 Gibson had fitted the same engine to a frame of four sprucewood wings, creating the

Multiplane. This aircraft was now controlled by foot rudders. But in one of aviation’s first examples of sponsor trouble, Gibson was grounded after a dispute with a promoter. In August 1911, Gibson’s assistant flew nearly one mile in Calgary before crashing the aircraft to splinters, ending Gibson’s interest in flight.

The Netherlands

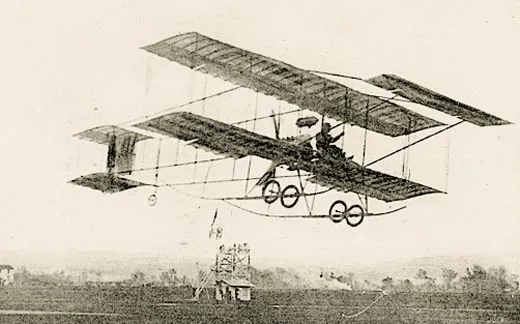

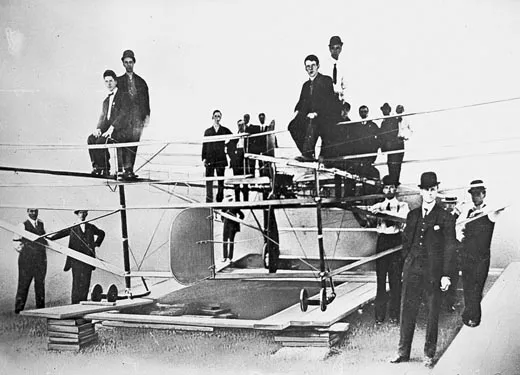

In the autumn of 1910, Frederick (“Frits”) Koolhoven, an engineer and race car driver, and Henri Wijnmalen, a former student of medicine, delivered what was hailed as the first all-Dutch aircraft: the Heidevogel (Heatherbird). A Dutch car dealer established a subsidiary to stage test flights by the pair (and, one assumes, draw potential car buyers). The Heidevogel turned out to be a near-exact copy of a Henri Farman biplane. The records on this airplane are scarce, but at least one photograph shows it flying.

Roger A. Mola is an Air & Space researcher.