The Bombing of Waziristan

In this rugged hiding place, outlaws like Osama bin Laden are rarely run to ground. The British learned that lesson in 1939.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/68/f368dcd5-0979-4e1f-96c5-537cb471a9de/bombing_of_waziristan_opener.jpg)

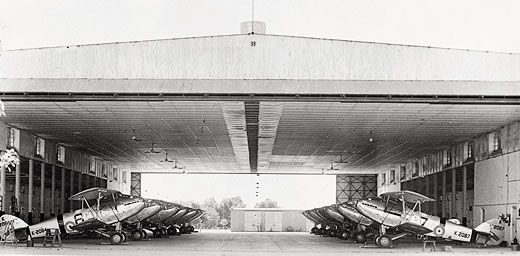

Since March 2007, Royal Air Force pilots of 39 Squadron have patrolled Afghanistan from control stations at Creech Air Force Base, near Las Vegas, Nevada. Flying MQ-1 Reaper unmanned combat airplanes, the pilots, along with their allies in the U.S. Air Force 15th Reconnaissance Squadron, have watched Afghan villages, deserts, and ancient mountains scroll across their video screens as they seek and sometimes strike the Taliban, al Qaeda, and other jihadists. The pilots see today, through the magic of a satellite link, landscapes almost identical to those their predecessors in 39 Squadron saw in the 1930s from the cockpits of Westland Wapiti biplanes and Hawker Harts.

On March 1, 1924, RAF Chief of the Air Staff Hugh Trenchard issued a directive entitled “Employment of Aircraft on the North-West Frontier of India.” It was stamped “SECRET” and opened with a mild declaration: “The problem of controlling the tribal territory…has always needed special treatment by reason of the psychology, social organization and mode of life of the tribesmen and the nature of the country they inhabit.”

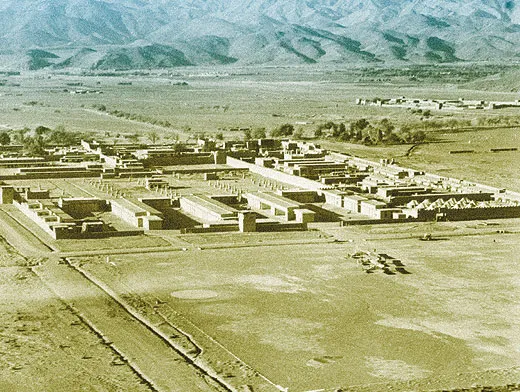

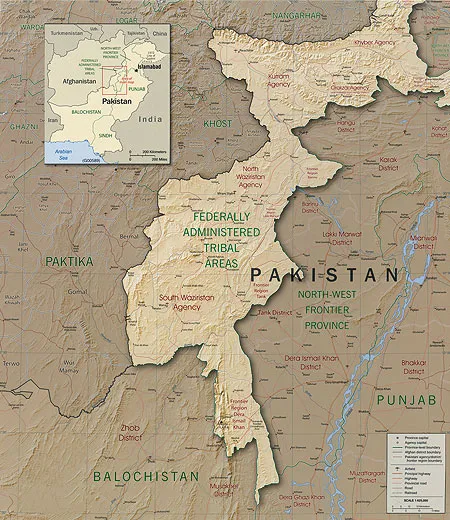

The North-West Frontier was a rough, fortress province on the edge of the British Empire, in what is now Pakistan. Since the mid-19th century, the Wazirs, Mahsuds, and other mountain tribes who lived in the area had harrassed the British by stealing cattle, looting, and kidnapping and ransoming British citizens. Stirred up by Britain’s two invasions of Afghanistan in the 1800s, tribesmen in the insular, autonomous district of Waziristan challenged British forces in the North-West Frontier, even after the 1919 armistice ending the third British-Afghan War.

The RAF squadrons sent to Miram Shah and other remote Waziristan bases were playing a part in what Rudyard Kipling immortalized in his 1900 novel Kim as “the Great Game.” Like the characters in the novel, the airmen were caught up in the struggle between Russia and Great Britain for dominance of south Asia. (Britain’s invasions of Afghanistan had been attempts to deter Russian expansion into that country.) The British and Indian soldiers patrolling the dangerous hills of Waziristan, however, and the airmen who came to assist them didn’t have time to think about grand strategies. They had their hands full defending against attacks on their convoys, forts, and patrols, some of them waged by the very militias the British had formed and armed to aid in their conquest of Afghanistan. To defend the British colonial territory, the RAF devised a new form of frontier warfare, which its strategists called “air policing.”

Read today, the 1924 directive on air policing will sound familiar to those who have watched the war in Afghanistan for the past decade. First, the 1924 strategy was punitive: If the tribesmen staged a raid or attack, the bombers would be called in. The directive recommended that action be immediate: “Hesitation or delay in dealing with uncivilized enemies are invariably interpreted as signs of weakness.” And it stated a philosophy that might have surprised the gentlemanly RAF and certainly foreshadowed modern controversies: “In warfare against savage tribes who do not conform to codes of civilized warfare[,] aerial bombardment is not necessarily limited in its methods or objectives by rules agreed upon in international law.”

Though the philosophy was radical, the practices of air policing were developed under codes that British soldiers of the time would have considered fair. Unless demands from the British government were met, the air policing protocols were set in motion. For example: Over a village where a lashkar, a hostile raiding party, was known to have originated, aircraft were sent to drop bilingual leaflets. The leaflets warned that unless demands like denying safe harbor to hostiles were met by a specified date, the village would be bombed. The leaflets strongly recommended the removal of women and children by that date, and suggested, with extraordinary obtuseness, that the villagers hand over the non-combatants to the care of those who were about to bomb their homes: “If you so desire, the government will take charge of them...and restore them to you unharmed when you make your submission.”

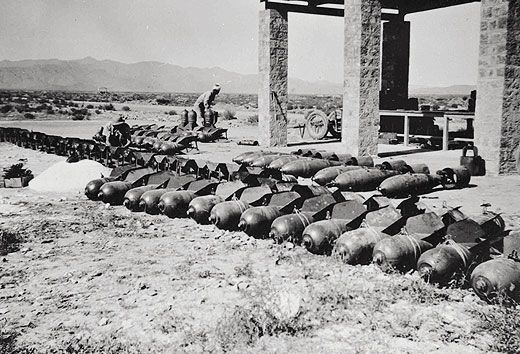

The warnings were often accompanied by bombing demonstrations staged nearby. The air directive recommended that on the specified date, strikes be conducted immediately, “to ensure the greatest concentration of men and animals around the village.” The bombs should therefore be “man-killing,” and machine guns were to be fired against any movement. “Incendiary bombs should be used for good effect against villages and crops.” Selection of the right bomb size was important: The document advised that 20-pound bombs “will only make a small hole in the huts of tribesmen, 112-lb bombs will be expected to blow off the roof, while 230-lb and larger bombs should destroy large houses.”

How these strategies would affect the population was predicted in the directive as well. “The enemy will as the result of such measures feel insecure at all times; men must hide in caves...cattle if not driven into caves must be grazed in small bunches at great labour...tillage of fields must cease....” Once a group submitted to the demands, pilots would drop another set of leaflets announcing “no further bombing” and that it was safe to return to village life.

It took a few years to build the air policing force. G.M. Knocker, later group captain of 28 Squadron, wrote in his diary in April 1922, “on 6th April word came...that some 2,000 Afghan and other wild men had laid siege to the fort at Wana [in South Waziristan] and that all available aircraft from 28 and other squadrons on the Frontier were to proceed to Tank [a base to the east of Wana].” This sounds like a prompt and capable response. But he continues, “Available aircraft of 28 Squadron consisted of one Bristol Fighter—my aircraft, and that was in none too good shape.” In August 1922, aircraft serviceability really was a sad state of affairs. “Out of 70 aircraft only seven were fit for operations,” writes Chaz Bowyer in The Flying Elephants: a history of No. 27 Sqn RFC-RAF 1915–69. “It was all due to funding: the RAF in India came under the Army budget.” There was considerable rivalry between the services, and the money went to the foot soldiers.

But by the late 1920s, new and more effective airplanes had arrived: The Westland Wapiti (a North American Indian word for “elk”), an open-cockpit, two-place biplane, replaced the DH.9A, and Hawker Harts and Audaxs were sent as light bombers and multi-purpose aircraft. The Wapiti was used extensively for dive bombing, which required aerobatic skill. Pilot Geoffrey Morely-Mower, later wing commander, wrote of the tactic, “The technique was to pass directly over the target, throttle back and pull the nose up sharply until the airspeed was within 20 mph of the stall. At this point full rudder is applied—it was called a stalled turn. With the nose pointing vertically upwards at low speed, the rudder wheels [rotates] the aircraft elegantly on its axis to a position heading vertically downwards. If you have judged it correctly you should be looking straight down at your target.”

But not having brakes, the aircraft were a challenge to taxi. “The only way to change direction was to put on full rudder and blip the throttle,” wrote the RAF pilot, meaning to toggle it quickly fore and aft. “If this was not judged perfectly, inertia would exaggerate the turn. Opposite rudder and more engine power had to be applied to retrieve the situation. This led to a buildup of speed.” If the pilot instinctively throttled back, the Wapiti would ground loop.

The tribal combatants had no aircraft to counter British bombers, of course, but just as the Taliban today manage to pilfer 7.62-mm ammunition intended for Afghan government forces, tribesmen in the interwar years captured .303 rifles and cartridges. So unless an aviator was on a dive bombing or strafing run, the rule was to stay above 3,000 feet, out of the range of the enemy’s rifle fire. “The tribesman is a good natural shot, and is fully alive to the necessity for deflection when shooting at fast moving aircraft,” warns the pocket-size 1939 manual Frontier Warfare—India (Army and Royal Air Force). However, if detailed reconnaissance required pilots to fly lower, they should “make full use of their speed, fly an irregular course, [and] use their weapons to keep down hostile fire....”

If a pilot were forced down over hostile territory, he was advised to “first remove the bolt from the Lewis gun and throw [the bolt] overboard.” On reaching the ground, every effort was to be made to burn the airplane “by firing a bullet or [flare] into the petrol tank.” And, if escape was out of the question, some advice was given, with typical British understatement: “It will be wisest to surrender with good grace and a bold demeanour, preferably to the older and more important-looking men among the crowd; the younger element is liable to be hot-headed and unpleasant.”

The British offered a reward of 9,000 rupees for return of a downed airman, and the promise generally resulted in fair treatment in captivity. Crash-landing in “black clouds and heavy rain” over western Waziristan in the summer of 1924, A.J. (Jack) Capel—later Air Vice Marshal—“tried to set alight the machine, but before we got it to burn we were surrounded on all sides by tribesmen, who quickly got hold of us,” he wrote to his sister. He reported that because of the reward offered, the Wazirs and Mahsuds fought over him. The Wazirs won, and a several days later, “I got sent up from the camp a good box of tinned food, a bottle of whisky and some beer and some clothes....” After three days, the ransom was paid, and he was released with a 1,000-rupee note from his abductors, which they included, he said, for his “inconvenience.”

Such hospitality couldn’t always be expected, so the RAF invented what they nicknamed “goli chits”—safe conduct letters for air crew. Goli is the Pashto word for ball. Rumor had it that tribesmen often castrated their captives. The chits promised a reward if the bearer were returned with all parts intact. A beer-drinking song in the mess summed up the ghastly prospect: “No balls at all. No balls at all. When your engine cuts out, you’ll have no balls at all.”

Although histories of the period recount ambushes and massacres of Indian and British Army ground troops, the surviving diaries and letters of pilots in the RAF squadrons indicate that the airmen managed to enjoy the gentleman’s life, even amid the mayhem of the frontier. G.M. Knocker, who spent 1918 to 1922 in India, recounted in his diary a jolly life with darts, dances (“only eight girls” at one), a bearer—personal servant—to attend his daily baths and press his uniforms, soccer and rugby games, and lots of “afternoon snoozes.” Wing Commander D.L. Allen, who flew DH.9A light day bombers and Bristol Fighters out of Risalpur from 1927 to 1929, wrote of Sunday afternoon tennis parties, “good hockey and football grounds, tennis and squash courts, polo, picnics and dances for all ranks.” Being stationed at a larger base, he had a better chance than Knocker did at female companionship: “there were usually some 70 eligible young women staying with relatives and friends, termed irreverently, the Fishing Fleet,” he wrote. “They were always in demand for dances and parties.”

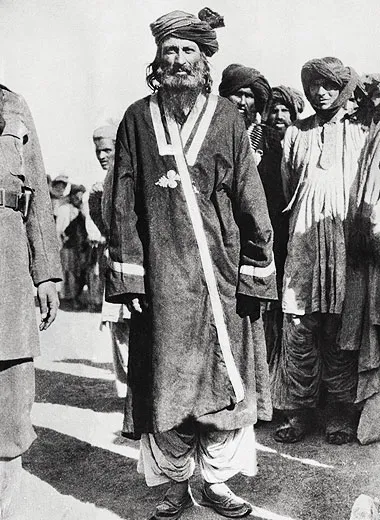

By the mid-1930s, the RAF’s air policing campaign was in full swing and integrated with British Army ground action. In November 1936, the conflict intensified. Mirza Ali Khan, a rebel fighter from the village of Ipi, led an ambush against two British marching columns in Waziristan’s long-peaceful Khaisora Valley, trapping the units and killing 14 soldiers. RAF air drops of ammunition and supplies saved the day, but the incident launched a multi-year campaign to capture Ali Khan, a Sufi mystic who became known as the faqir of Ipi.

Up to this point, Sergeant Albert Edward Holloway of 60 Squadron, who had arrived at Kohat at the end of 1934, had seen little offensive action. His logbook records reconnaissance and cross-country trips, drogue attack practice, and photo missions in Westland Wapitis. On New Year’s Eve 1936, however, he finally got a taste of air policing. “Active operations—bombing Arsal Kot,” reads his entry that day. Arsal Kot was the fortified hideout of the faqir, and Holloway didn’t do much reveling that night. Next morning, New Year’s Day, he “re-armed at Miram Shah” with 230-pound, high-explosive bombs and flew two more missions in his Wapiti, blasting the faqir’s headquarters.

The faqir escaped, and called for a jihad against the British. Emboldened by his intransigence, other tribes and groups, notably the Bhittanis of Waziristan, joined his effort. Thousands of tribesmen were soon conducting raids all over the frontier. The British stepped up their efforts to get the faqir by conducting what they called “blockades”: keeping the tribes suspected of sympathy with the faqir from their livelihoods. Bombing operations prevented the watering of livestock and thwarted the plowing or harvesting of crops, according to Waging War in Waziristan: The British Struggle in the Land of Bin Laden, 1849–1947, a book recently published by Andrew M. Roe. For the first 10 days of March 1937, Pilot Officer A.M.A. Birch, also flying Westland Wapitis, flew several missions of “convoy escort,” or “road recce to Jandola,” often from 8,000 feet, all the while fully loaded with bombs. Later he pasted a photo in his logbook captioned “20-pound bombs bursting among cattle in Razmak area.”

The Karesti area, southeast of Miram Shah, was one of the first to be blockaded. Again Holloway joined the fray. Fresh from a three-month leave in England and loaded up with four 112-pound bombs, he hit the village while spraying 216 rounds from his Lewis gun. As he wheeled around his rear gunner shot off 384 rounds. Pulling away, he wrote later, he noticed he had been “shot through strut, spark plug blown out.” He flew low along the Tochi River Valley to the base at Miram Shah for repairs.

In the campaign to capture the faqir, one of the largest operations became known as the Bhittani Blockade. In September 1937, Holloway flew 22 Wapiti sorties against Bhittani, usually carrying four 20-pound and two 112-pound bombs and terrorizing enemy livestock with his front and rear guns. Logbook entries read: “Cattle dispersed with casualties”; “Camels and sheep dispersed.”

The faqir shifted from village to village and group to group, with each protecting him in turn; through 1939, the Brits attacked in a cat-and-mouse game. Most of the RAF strength took part: Five squadrons from Miram Shah, Arawali, Kohat, and other bases flew Wapitis, Audaxs, Harts, Bristol Fighters, and Valencia bombers. Once a local council had satisfied the British Political Agent that no more hostiles were being protected, leaflets were dropped announcing “Whereas the government are satisfied that the tribe desires peace and have dissociated themselves from their hostiles...it is safe for you to return to your home....” Kindly, the notices added “TAKE CARE: do not touch any unexploded bombs....” In some areas, such as the Tori Khel, the RAF bombed, on and off, for eight months, expending 1,650 flying hours, 1,600 bombs, and 68,000 machine gun rounds.

The faqir was never caught. By 1939 he was operating from across the border in Afghanistan, and increasing tensions in Europe were drawing the RAF away from Waziristan. In the 1930s, the British colonial rule in India began to fade. Already by 1932, the Indian air force had been created in anticipation of independence; indeed, many Indian units flew alongside the RAF in punitive strikes against the militant tribes. In January 1935, the parliament in London introduced the Government of India Bill, granting India self-government.

In 2010, Royal Air Force Flight Lieutenant Duncan Swainston of 39 Squadron flew MQ-1 Reapers monitoring the area of the world where the Great Game had been played. He said that the Royal Air Force is conducting missions only in Afghanistan, and that he is not flying over any part of Pakistan. The United States is. Although the Pentagon and Department of State don’t acknowledge the attacks, Pakistani security organizations as well as the Associated Press and Reuters have reported 75 missile strikes in Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas between September 1, 2010, and the end of February. Many of them targeted the same villages that protected the faqir in the 1920s: Datta Khel, for example, which was once a garrison staffed by recruits from local tribes led by British officers, and Mohammed Khel, just 20 miles west of the old RAF base at Miram Shah. The drones targeted supporters of Osama bin Laden, the new faqir who for almost 10 years escaped his hunters.

A U.S. Naval Test Pilot School graduate, Calgary-based freelance writer Graham Chandler spent eight months in Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province conducting research for a Ph.D. in archaeology.