The Curious Case of Edgar Mix

The celebrated aeronaut found Earth-bound life difficult to navigate.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The_curious_case_of_edgar_mix_FLASH.jpg)

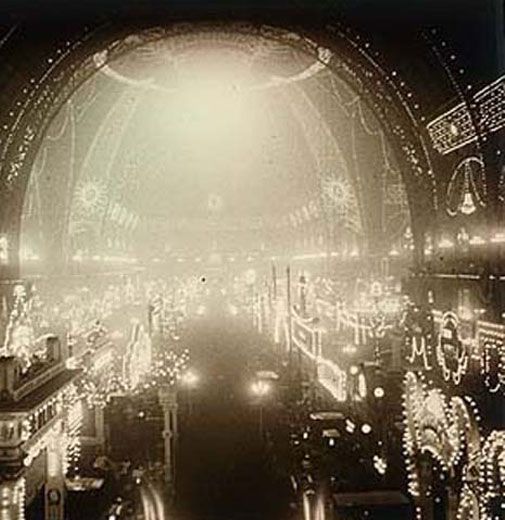

For aviation enthusiasts at the turn of the century, Paris was the place to be. In 1901, thousands thronged the Parc de Saint-Cloud on the city’s outskirts to watch Alberto Santos-Dumont, competing for the Deutsch Prize, take off in his one-man powered airship to fly to the Eiffel Tower. The wealthy aeronaut, who won the city’s heart by splitting his prize money between his mechanics and the city’s 4,000 registered beggars, pronounced the seven-mile trip “remarkably intoxicating.” But by 1906, when Paris hosted the first Gordon Bennett cup, an international distance race for balloonists, Santos-Dumont had moved on, and was creating a sensation with heavier-than-air craft. The citizens of Paris were treated to two types of aerial spectacles: balloons and airships, which had entertained them for more than a century, and a new invention, which would dominate the century ahead: the airplane. Fortunately, one of the flight enthusiasts living in Paris at the time was Edgar Mix, an American engineer and amateur photographer. From Mix’s photographs, historians now have a view of the transition in aircraft that occurred in Paris more than 100 years ago.

“Today, Mix is a very obscure character,” says Melissa Keiser, chief photography archivist at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. “He learned how to fly balloons in Paris, and that’s apparently where he became interested in aviation. Ballooning became a passionate hobby for him.”

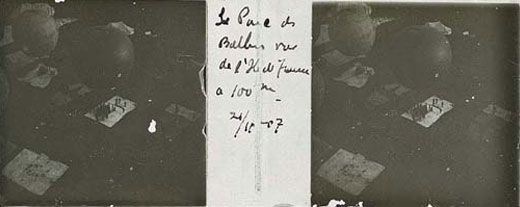

Mix became so fascinated by ballooning that he persuaded famed aeronaut Alfred Leblanc to accept him as copilot of the Île de France in the second annual Gordon Bennett International Balloon Race, set in St. Louis, Missouri, in October 1907.

“Mix was an avid photographer, and seems to have carried his camera everywhere,” says Keiser. “His photographs give us an intimate portrait of the life of a gentleman balloonist in the pre-World War I period, and—since he carried his camera aloft—include beautiful early aerial views of Paris and its environs.”

Mix was equally interested in documenting his new hobby, and took hundreds of photographs, some of which are in the Museum’s collections. In 1998, a descendant gave the Museum nearly 700 stereographic glass plates from Mix’s collection, most having to do with early aviation and ballooning.

Although a German team won the 1907 race, Leblanc and Mix placed a close second, landing in Hubertsville, New Jersey, after traveling some 875 miles, just five miles short of the German record. “Had we known that the Pommern was going to beat us [by] only a few miles we would have gone 50 miles out into the ocean to win the race,” Mix told the Columbus (Ohio) Citizen. “We had plenty of ballast left.”

Mix’s interest in aviation grew. He served as a judge at the Reims Air Meet in August 1909, hobnobbing with such well-known aviators as Louis Blériot, Hubert Latham, Henri Farman, and Glenn Curtiss. By October that year, Mix decided to borrow a balloon and enter the 1909 Bennett race, held this time in Zurich, Switzerland. Piloting the America II, Mix traveled 696 miles to a forest north of what is now Warsaw, Poland. He won the race, but as he headed by train back to Paris, he received a telegram informing him that his win was being contested by a witness who claimed Mix’s balloon had touched down earlier in the race—grounds for disqualification.

Mix explained to race officials and reporters that near Prague, his balloon had been dragged to the ground. “The guide rope trailing beneath the basket struck the ground in a town or village,” Mix told the judges. “We could not make out the dimensions of the place, owing to the thick fog. Several persons caught hold of the rope, notwithstanding my protest, and, despite my endeavors to make them let go, dragged the balloon to earth. The basket touched the ground, and rested there probably between five and seven minutes, until I had been able to persuade the people to let go.” After much debate, the race organizers ruled that Mix could keep the trophy.

But the internationally renowned balloonist never competed again. And here the story takes a strange turn: Just two years later, Mix allegedly penned a suicide note and jumped from a mail boat headed from Dover to Calais. His body was never found.

The balloonist’s two sisters, living in Massachusetts, were convinced their brother was murdered, and asked the U.S. State Department to investigate. “They said he was active, he was happy,” says Scott Caputo, an independent researcher based in Columbus, Ohio, who is writing a book about Mix. “They did say he had a lot of enemies—other aeronauts. Were there bad feelings because of the decision in 1909 to award him the prize? I don’t think that the sisters’ cry for an investigation was ever given any serious consideration.”

We will never know the truth of Mix’s death. But the photographs he left behind record those brief years when balloons competed for the public’s attention with powered craft made of wood, cloth, and wire, and no one knew which kind of flight would eventually transform the world.

Rebecca Maksel is an Air & Space associate editor.