The Daring Mr. Moisant

The most celebrated American aviator of 1910 took up flying as an act of revenge.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/moisant-flash.jpg)

Trivia question: Why is the three-letter identifier for Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport “MSY” instead of “NOI” or something equally intuitive? No? It stands for Moisant Stock Yards, the name of the land upon which the airport was constructed. And who, you might wonder, was Moisant?

A century ago John Bevins Moisant was every bit as famous as Glenn Curtiss and the Wright boys—maybe more so, because the small, balding American was considered the world’s most daring aviator. His story appeared in comic books, his profile ran in women’s magazines, and scientific journals reported on his construction of an aluminum airplane, which had never been built. “Impossible,” cried the Wrights, who overlooked the fact that Moisant had always been a revolutionary.

John Moisant was born in Chicago in 1875, one of eight children and the youngest of four brothers. After the death of their parents the siblings moved to El Salvador and bought a coffee plantation. In 1907 the two elder brothers were arrested on charges of plotting to overthrow the country’s tyrannical president, Fernando Figueroa—charges cooked up after the Moisants refused to give bribes to the corrupt regime.

With the U.S. State Department refusing to intercede on his brothers’ behalf, John Moisant resolved to free them of his own accord, and, aided by neighboring Nicaragua, a bitter enemy of El Salvador, he acquired a gunboat and 300 soldiers. What ensued was one of the most daring attempts at regime change ever seen, but the insurgents were eventually put to flight by the Salvodoran army.

Figueroa put a price on John Moisant’s head and fixed a date for the execution of his brothers. This prompted the U.S. government to finally step in, and President Theodore Roosevelt warned of dire consequences if the Americans were killed. The brothers were soon released and the family, all except John, were allowed to return to their plantation.

Moisant went into banking in neighboring Guatemala, but President Figueroa was never far from his thoughts. In early 1909 Moisant read a newspaper article about the evolution of the airplane, and was struck by an idea: He would learn to fly, then return to Salvador to finish his revolution by air.

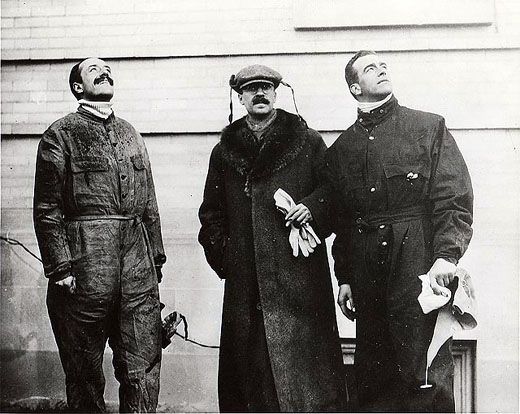

Moisant travelled to Europe and enrolled in a French aviation school, mastering the art of flying with astonishing ease. On August 17, 1910 he became the first aviator to cross the English Channel with a passenger, touching down in a field of oats six miles inland from the English coast. Standing beside the passenger [his French mechanic] and surrounded by impressed reporters, Moisant revealed that, “I took up flying as a hobby eight or nine months ago. This is the sixth time I have been in the air, and the machine I am using is the only one I have ever flown in.”

Moisant was lauded on both sides of the Channel, with the French newspaper France Patrie hailing his “energy, audacity and intrepidity.” The British in particular were fascinated by the American aviator, a man with “eyes of agate,” who was small in stature [he was 5 feet 3 inches] but big in heart. “One would expect that this journey of his across the Channel would knock his nerves up,” wrote the Westminster Gazette, “ but he maintains a calm equal to that of the Trafalgar Square lions.”

Moisant’s popularity didn’t go unnoticed by Cortlandt Field Bishop, president of the Aero Club of America, who was in England signing up pilots to compete in the prestigious International Aviation Cup being held that fall at New York’s Belmont Park. In Moisant Bishop saw an American capable of challenging Europe’s finest aviators.

Moisant agreed to represent America, and arrived home on October 8 to be greeted by hordes of wellwishers. He was tailed by the press wherever he went, and though he refused to answer questions concerning El Salvador, he was happy to talk on all subjects aeronautical. Moisant used an interview with the New York Evening Sun to criticise those who saw no potential in the aircraft as a military weapon. “People talk of shooting at flying machines from the ground and warding off an attack in that way. We can travel seventy miles an hour, more than that soon, and can go up 5,000 feet or more. Can they hit us under those conditions?” Moisant also predicted that future generations of Americans “will use airplanes as we use automobiles.”

These colorful views made Moisant a hit with reporters, and once the Belmont Park meet got underway on October 22, his brazen flying turned him into the fans’ favorite, too. Even though conditions in the first few days of the meet were wet and windy, Moisant still put on a show for the crowd while other aviators cowered in their hangars. Such audactity didn’t sit well with his rivals. The Wrights’ top pilot, Walter Brookins, described Moisant’s flight across the English Channel as “foolish,” adding: “He’s lucky he didn’t break his neck…an aviator must acquire a fine judgment of direction, of speed and of distance.”

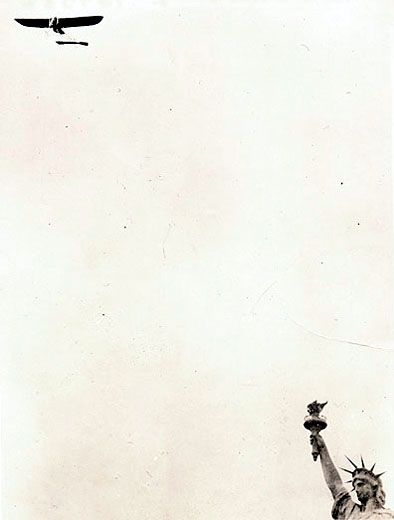

Moisant knew he had no chance of challenging for the blue ribbon event of the meet, the International Aviation Cup (20 laps of a five-kilometer course), because his 50-horsepower Blériot monoplane lacked the power of the British and French 100-horsepower machines. Instead Moisant had his eyes on another prize—the $10,000 Statue of Liberty race. The event was the brainchild of a New York businessman, Thomas Ryan, who a fortnight earlier had suggested to the organizers a race from Belmont Park to the Statue of Liberty and back. The safest route—cross-country to the sea and then along the coastline—was approximately 66 miles, whereas the direct route was only 33 miles. But as the New York Times pointed out, the shortcut would take the aviators “over the populous sections of South Brooklyn.”

Wilbur Wright was aghast at the idea, telling reporters he was “strongly opposed to flying over cities…. While it is an aviator’s own business whether he decides or not to risk his own neck, he has no right to endanger the lives of others.” The Wright brothers forbade any of their aviators from entering the race on October 30.

In the end only three pilots entered the Statue of Liberty race: Count Jacques de Lesseps, a French aristocrat, Claude Grahame-White, the dashing Englishman who had won the International Aviation Cup the day before, and Moisant. According to one newspaper report, “fully one million persons in all neighborhoods of the city” were on the streets waiting for the race to pass overhead. The three fliers took off at staggered intervals, de Lesseps the first to leave and Moisant the last. The Frenchman completed the course in 41 minutes, Grahame-White six minutes faster, and Moisant returned in 34 minutes and 38 seconds, shaving 43 seconds off the Englishman’s time after taking a more direct route than his rivals. The 75,000 spectators in Belmont Park went wild.

Enriched with the money he’d made from the Meet, Moisant formed a traveling show, the “Moisant International Aviators” (one of whom was the famous French pilot Roland Garros), and for the rest of the year they toured the United States thrilling fans with aeronautical acrobatics. In late December they were in New Orleans, where Moisant was soon eyeing a $4,000 prize tabled by the French tire manufacturer, Andre Michelin, for the longest sustained flight of the year. Moisant planned to turn his attention to manufacturing his aluminum airplanes in 1911, the protype of which he had already tested. But some of his team were becoming concerned by Moisant’s increasing recklessness in the air. His business manager, Albert Levino, told him to be more prudent. Moisant shrugged off the advice, saying, “I don’t expect to die in an airplane flight.”

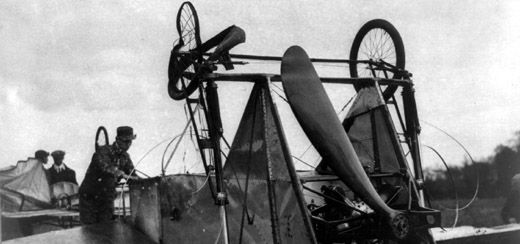

Moisant woke early on the morning of Saturday, December 31, in more of a frenzy of activity than usual. He had only a few hours before the window closed on Michelin’s prize. He took-off at 10 a.m. from New Orleans’ City Park aviation field, and began to entertain the crowd with some characteristically daring stunts. Suddenly his machine got caught in an air pocket and plunged nose-first into the ground. The first people to reach the wreckage were a group of railroad laborers who found Moisant lying in some long grass, without a bruise on his body, and with not the “slightest trace of fear or pain” on his face. His neck was broken and death had been instantaneous.

Where Moisant met his end was later transformed into land for cattle, and the owners named them the Moisant Stock Yards in honour of the aviator. Later they sold the 1,360 acres to the New Orleans authorities, who turned them into an airfield called Moisant’s Field by 1946, when the city’s first commercial air service began. In 2001 it became the Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport.

So next time you see the letters MSY on your flight tag, spare a thought for John Moisant, the most visionary man in American aviation a century ago. Shortly before his death he was asked by a reporter if he seriously believed the aluminum airplane had a future. “That’s one of the greatest troubles with airplanes today, and the reason they are not safer and a greater commercial possibility,” replied Moisant. “Their construction is too frail and there are too many wires and the wings are too flimsy. Would you expect an automobile to be safe if it had a canvas body and a lot of little wires to work it by?”