The Do-Everything Bomber

With its bid to replace the Convair B-36 bomber, did Douglas promise too much?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/05B_DJ10-flash.jpg)

On January 26, 1950, when General Curtis E. LeMay, commander of the U.S. Air Force Strategic Air Command, attended yet another conference to discuss the next U.S. long-range heavy bomber, his mind was likely already made up. The Convair B-36 was soon to be obsolete, and a variety of successors had been proposed. But Boeing bombers had served the U.S. military well during World War II, and if LeMay got his way—and he usually did—the next big bomber would be another Boeing product: the B-52 Stratofortress.

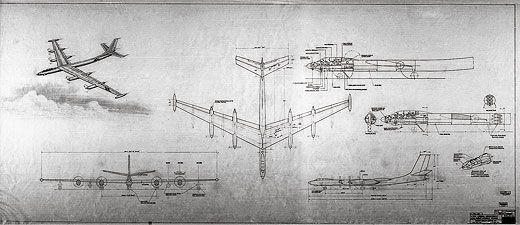

The potential contract was huge, and U.S. aircraft manufacturers brought ambitious proposals to the table. One of the designs—the Model 1211-J—came from the Douglas Aircraft Company in Santa Monica, California. Never had a bomber looked so capable—on paper.

Powered by four turboprop engines, the Model 1211-J was a colossus—160 feet long with a wingspan of 227 feet, about the size of the Convair behemoth it was to replace. It was designed around a new 43,000-pound conventional bomb but could carry nuclear weapons as well. It could also carry its own fighter escorts, as parasites under its immense wings. A variety of fighter types were suggested, including Douglas' new ogival-wing jet, the F4D Skyray. The fighters' jet engines were to be powered up to assist the carrier bomber during takeoff; refueling of the fighters was to take place while they were stowed on the mothership's underwing pylons.

Though the concept of parasite aircraft had an appealing ingenuity, flying them was fraught with difficulty. Flight testing had revealed that turbulent airflow would form under the carrier aircraft, causing severe problems as the fighter attempted to reattach itself to the host aircraft.

Would the Model 1211-J have succeeded as a parasite platform? "The combination of the totally new bomber and the totally new fighter, attaching itself in the direct path of the turboprop propeller wash, is frightening to contemplate," says Walt Boyne, a retired B-52 pilot and former director of the National Air and Space Museum. "The inclusion almost smacks of either desperation or a sense of humor on the designers' part." (A few years later, the parasite concept was rendered obsolete by the use of inflight refueling.)

In place of the parasite fighters, large underwing drop tanks and special-purpose pods could be substituted to provide, according to the Douglas proposal, "extreme versatility in operations." Douglas engineers imagined pods—"droppable or not as desired," the proposal states—that could carry reconnaissance or radar equipment, countermeasures, even personnel to supplement the bomber's nine-man crew. One drawing shows the pods in a photo-reconnaissance configuration, complete with cameras and even a small film-processing lab.

Without the parasites, the Douglas bomber could defend itself with a choice of radar-controlled 20-mm cannon or Hughes MX-904 self-guided missiles, stored in an internal rotary launcher like an oversized Colt six-shooter.

The Douglas team had also proposed droppable takeoff gear positioned under the outer section of the 1211-J's enormous wings. "Using droppable gear is always a last resort," says Boyne. "The B-52 had retractable tip gear, which was a heavier but more sensible solution."

By including so many options, the Model 1211-J's designers tried to make the bomber a paragon of multi-tasking self-sufficiency. They had hoped to sell the Air Force not just a single bomber but a family of aircraft, with a variety of airframes to choose from, including custom options and mission-specific add-ons. But would asking so much of the 1211-J compromise its ability to do its main job: put bombs on target? "I've always been a minimalist in aircraft design," says aerospace historian and author Dick Hallion. "When you take a look at this Douglas design, there's a lot of frou-frou. There are a lot of things here that wouldn't work out well operationally. There are a lot of issues that make turboprops unreliable: gearbox issues, shafting issues, the propellers themselves. These are all complex problems that need to be worked out." And even if Douglas engineers could have solved the 1211-J's problems, the bomber's fussy design would have made it a maintenance nightmare.

The Douglas designers of course hoped to dazzle the Air Force with possibility, but no matter how much versatility they put into the 1211-J, it wasn't enough to interest LeMay, who kept pushing for the more practical, turbojet-powered B-52. In the spring of 1951, Air Force chief of staff General Hoyt Vandenberg approved the Boeing proposal. Given the stupendous—and ongoing—career of the B-52, this was certainly a wise decision.

John Aldaz and Sir George Cox have collected hundreds of original aircraft manufacturer models.