The Family He Left Behind

Fifty years ago, Yuri Gagarin left earth. When he came back, everything changed.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The_Family_he_Left_Behind_7_FLASH.jpg)

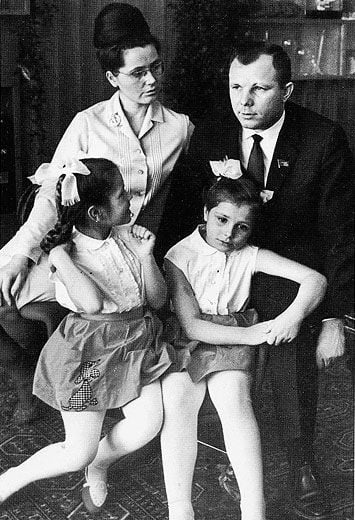

This month the heirs of Yuri Gagarin will celebrate the 50th anniversary of his flight into orbit. They are his daughters and his widow, his nieces and cousins, his space-going peers, his former rivals, millions of us who knew him only from black-and-white newsreels as the first man in space, and a dwindling few who remember first-hand how far he had to rise to reach the stars.

It was April 12, 1961, when a dreamy boy born to poverty and flames on the Eastern Front of the Second World War flew weightless for nearly two hours in a capsule called Vostok—“the East.” Barely seven years later, when he was 34 years old, the spacefaring hero with the famous, easy smile was killed in a crash of his own MiG-15UTI jet, his hand still on the joystick when he and his instructor copilot hit the trees. He is one of history’s bravest and most tragic adventurers.

I am searching for the father and husband and friend behind the chiseled face on a statue or gleaming idol on a coin. But his elder daughter seems more comfortable discussing his public persona, calling his flight “one of the main achievements that took place over the last 100 years, not only for this country but for mankind.”

She is telling me this in an office above one of the world’s great treasuries, the exhibition halls of the Moscow Kremlin, where czarist—and later, Communist—power presided over centuries of serfdom, socialism, and sacrifice. Elena Yurievna Gagarina was two years and two days old when her father lifted off from Baikonur in Kazakhstan, and not quite 10 when he died. Today, she is the director of the Kremlin State Museum, where she is the guardian of imperial robes, royal carriages, and Fabergé eggs.

It is difficult to imagine a more elegant workplace, or a more elegant woman. When Barack and Michelle Obama visited Moscow in 2009, it was Elena who escorted the First Lady through the galleries. Fluent in English, she is the custodian not only of Russia’s royal jewels but also of every Yuri Gagarin statue, every postal tribute, and every published encomium. All must pass her personal inspection.

“There are good sculptures and bad sculptures, good stamps and bad stamps,” she says. “This is the role which is given to me by law: that all images of my father and stories of his life I should see.” Fine art, she says, is all that ever attracted her, even as her father was reaching for—and falling from—the heights of space exploration and fame. “Each of us in our family followed a different path,” she says. “My mother was a doctor, my sister an economist. Our parents wanted us to follow our own interests.”

Elena worked her way up to become the curator of 18th century English drawings and engravings at Moscow’s Pushkin Museum. (Her only child, a daughter, works at the Kremlin with her.) It is natural to wonder whether someone named, say, Kuznetsova—the Russian “Smith”—would have risen as high as Yuri Gagarin’s daughter. But Elena waves off this petty conjecture. “I never used my name for my career,” she says. “My field of interest is very different from anything connected with space travel. I always wanted to be an art historian from the earliest age. But still, of course, people know my name. Everyone has a story about my father. Everyone has a story to tell about the 12th of April.”

Elena herself doesn’t remember much of that day. “When my father went into space, I don’t think that at that period I understood it quite well,” she says. “I was too young. All the people I encountered every day—our friends, our neighbors—were connected with the space project.”

No one at the time knew much about the engineering challenges of spaceflight. “The cosmonauts understood that it was 50-50 if the flight would be successful or not. The general consensus was that it was safe. But Father had complete trust in the chief designer [Sergei Korolev]. Korolev loved him very much.”

The second daughter, Galina Yurievna Gagarina, was 36 days old when her father flew. “When I was a child, I lived as every child does,” she says. “We hadn’t any special teacher or special school or special conditions of life. Our city—Star City—was a very special place. From the very beginning, I knew that. But for us, it was normal. At school, I studied with many different children. Not all were the children of cosmonauts.”

By the time Galina reached fourth grade, American astronauts were on the moon. If the Gagarina girls had been unique as infants, their celebrity no longer was so singular. A lot of the dads at Star City had gone into space.

We are in Galina’s office at Plekhanov University in Moscow, where she has been a professor of economics for 25 years. Galina, who is married to a pediatrician from the Kamchatka peninsula in Russia’s far east, has one child: a boy, now 17, named Yuri. Like her sister, she is fluent in English.

Galina’s professional life has been steadfastly and unromantically Earth-based. When we meet, she’s wearing a sweater and clunky beads. At Plekhanov, she teaches courses in Russian political economy and “Allocation of Productive Forces.” Unlike her sister, she has never been to the United States. But 30-plus years ago, she did meet Fidel Castro.

Her office, on the third floor of the college’s main building, is cramped and unadorned, save for a large map of the Russian Federation and a calendar that features another famous celestial traveler: Le Petit Prince, the creation of French writer and pilot Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. On the calendar is a quotation from that wonderful book: “All men have the stars.”

In April 1961, of course, only one man had them.

“For the Soviet Union, it was a victory of engineering that this was accomplished only 15 years after victory in the war,” Galina says. “And of course, there was the philosophic aspect as well, because mankind understood the possibilities, the great possibilities of the future.” Like Elena, she hears daily from older Russians who want to share memories of her father and of his flight, memories of a mission far beyond her recollection.

“Of course, our family was very famous,” she says. “People always treated us with special attention and curiosity, which had its impact on our behavior in public, as we always had to, and still have to, control practically every step and every word.”

After his flight, she says, her father “had a huge circle of additional responsibilities.” Promoted to deputy director of the cosmonaut corps, he was also made a member of the Supreme Soviet, appointed chairman of the Soviet-Cuban Friendship Society, and named head of the Federation of Water Sports, among other duties. With all his travels, both domestic and foreign, “he didn’t have much time to spend with the family,” says Galina. “But we always spent every vacation together, and every Sunday, when he could, we would go to the countryside or visit someone.”

Three hours west of Moscow stands the unpronounceable city of Gzhatsk. Here on the flatlands of the Russian empire, invaders from Genghis Khan to Napoleon to Hitler unfurled their flags and met their fate. Now there is a four-lane highway that crawls through Moscow’s exploding, modern, high-rise suburbs—with fitness centers, Audi dealers, McDonald’s with McCafés—then flies as straight as an arrow toward Smolensk, Minsk, Warsaw, and Berlin.

Buffeted by the ambitions of emperors, the peasants here worked the fields and dug wells. They work them still. I am drinking now from one of those wells, behind a wooden farmhouse called an izba, a few miles outside Gzhatsk in a hamlet called Klushino. This is the re-created birthplace and childhood home of Yuri Gagarin, and visitors see his father’s carpentry tools, an old pendulum clock, irons for the fire, a spinning wheel, a butter churn, a samovar, and Orthodox icons in the rafters.

A few yards away is the earthen dugout where Alexei and Anna Gagarin and their sons Yuri and Boris were forced to live like prairie dogs when the Nazis “borrowed” their house. The oldest son, Valentin, and a daughter, Zoya, already had been shanghaied to Berlin as laborers in service of the Thousand-Year Reich.

Tatiana Vladimirovna Igorevich has spent more than a decade as a guide at the reconstructed house-museum. The Russian spirit, she tells my interpreter, is accustomed to privation. “Struggle for everything,” she says. “Work hard every moment. Get used to hardship. Love the nation. Hate the enemy. That is the Russian soul.”

A few yards down the street, I find a man named Yevgeni Yakovlevich Derbenkov in the house he has lived in for nearly all of his 78 years. Fur hat, felt boots, gold teeth. “I’m proud and happy that my old childhood friend who used to run around this village barefoot with me, despite all the hardships, he went to space,” Derbenkov tells my interpreter. (Had Gagarin lived, he would be 77.)

Derbenkov still recalls that day. “It really was amazing. When we heard that the one who returned from space was our Yuri, we asked each other ‘Our Yuri went to space?’ And we said ‘Of course! Who else from Klushino would go?’ ”

Back at the wooden house, I ask Tatiana if she can imagine coming from this homely place and reaching the stars. “All Russians come from this,” she flatly replies.

When the war ended, the original izba was disassembled by Alexei Gagarin and moved to the heart of Gzhatsk. Having survived their German captivity, Valentin and Zoya returned home. Zoya later married a man named Dmitri and gave birth to a daughter named Tamara. The baby’s godfather was Yuri Gagarin, age 13. The entire extended family lived in the same little house.

In 1961, after Yuri went into space, the izba there also became a museum, and Gzhatsk was renamed Gagarin, in his honor. Since the early 1970s, Gagarin’s godchild, Tamara Dmitrievna, has been the curator at the Gagarin house-museum. She’s never worked anywhere else.

We’re in the kitchen of the ancient farmhouse, the Space Age version of Lincoln’s log cabin. I ask her how the family changed when her godfather uncle went into space. “Life as it had been going pretty much carried on,” she replies. “What was there to expect? It was Yuri who went to the cosmos, not us. What could change?” Her uncle, she adds, didn’t seem much changed by the flight. “He grew in the political sense of his own importance. But as an individual, he was the same open person.”

If anything, she says, the town was changed more than the Gagarin family was. “A lot changed in the city. There was practically a rebirth. It was a small city without central heating, sewers, or running water. The infrastructure was greatly modernized. New housing projects were built: a new school, a hospital, a polyclinic [an outpatient clinic], a House of Culture.”

Today, those improvements show their age; no one would rank downtown Gagarin as a showplace of post-Soviet success. In the heart of what was Gzhatsk, I see no fitness centers, no Audi dealers, no McDonald’s. There is only the tired Hotel Vostok and a couple of dark, smoky restaurants. But then, on a gray, frigid, and snowy January day, few Russian towns invite a pleasant stroll.

Back in Moscow, I meet with one of Gagarin’s friends from the cosmonaut corps at the Association of Veterans of War and Military Service, where a large photograph of Josef Stalin hangs in the lobby. Lieutenant General Viktor Gorbatko, the 20th Soviet in space, is wearing the red ribbons and gold stars that identify him as a twice-honored Hero of the Soviet Union. Selected as a cosmonaut in 1960, he flew three Soyuz missions, spending nearly a month total aboard the Salyut 5 and 6 space stations in 1977 and 1980. Is he, at 76, ready to go back into space? “Only in my dreams,” he tells my interpreter.

I ask Gorbatko if he thought fame had changed his friend. “Nyet!” he says. “Proud as I am to have been his close acquaintance, and I could use the word ‘friend,’ Yuri remained absolutely like everyone else. When he became director of the [cosmonaut] research center he could be demanding, but he never changed as a person.”

Gagarin’s Soviet gold star was number 11,175. The cosmonaut liked to tell audiences that he was no more special than the 11,174 heroes who had come before him. But none, of course, had ridden a flaming rocket, or watched from orbit as the sun dropped below the horizon.

Now I am in the office of Marina Popovich at the Nicholas Roerich Museum, and she is showing me her medal. It is number 18,874. She is a former test pilot and retired Soviet air force colonel. Nicknamed “Madame MiG,” Popovich is one of Russia’s most accomplished woman pilots and the ex-wife of Pavel Popovich, the fourth Soviet in space. “All of the wives thought that their husband would go first,” she recalls. “You felt a hope, a fear, and a feeling of awe. It was an unbelievable sense of pride and wonder. It was glorious.... Gagarin acted quite properly. Despite all the cameras, all the telegrams, he just smiled as if going into space was what he did all the time. A person with a good upbringing wouldn’t be blinded by his own glory.”

Despite having set 101 aviation world records (28 as copilot), Marina Popovich never got a capsule of her own. I ask whether she would have surrendered 50 years of her life, as Gagarin did, to have been the first in space. “I would have made the trade without a second thought,” she replies.

The wife whose husband did go first has taken little part in public remembrance for more than 40 years, but may turn out for ceremonies at the Kremlin this year, her daughter Galina says. Still living in Star City, Valentina Gagarina is in her late 70s now, retired from the practice of medicine and tending—she tells her friends—to a fragile and perhaps still-broken heart. She turned down my requests for an interview (her last, with a Russian journalist, was in 1978). “It is very difficult for her to meet people,” explains Elena, her older daughter.

“She was more of the home type,” Viktor Gorbatko tells me. “I wouldn’t say that the flight changed her. She didn’t stand out then, and she doesn’t really stand out even now.”

Valentina had met and married a dashing young pilot only to find herself tethered to the most famous man in the world. After Yuri’s death, the Gagarin family received government support: a lifetime pension for his widow and separate pensions for the daughters until adulthood. Widowed in her 30s, Valentina raised two girls to be successful, educated women. Meanwhile, the coming of glasnost led to rumors of Gagarin’s debauchery and conspiracy: that post-flight, he had become a boozy womanizer; that Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev, who was not enamored of Gagarin the way his predecessor Nikita Khrushchev was, had ordered the cosmonaut’s MiG shot down. The rumors remain sensitive subjects that neither daughter will discuss.

As Valentina saw it, “freedom of speech turned into a state where there were no limitations,” says Tamara, her niece. “She just closed herself.”

“She is a very good and very honest woman,” says Marina Popovich, her neighbor. “I wouldn’t say that about all the [cosmonauts’] wives.”

These are the Gagarins on the eve of half a century of human spaceflight: a shy, reclusive widow; one daughter working among the ghosts and grandeur of royalty; the other instructing tomorrow’s capitalists; scattered in-laws, nieces, and cousins.

One relative lives in Missouri. Anna Gagarina, 29, is the only descendant of the Klushino clan to have settled in the United States. The granddaughter of Yuri’s younger brother Boris, she has been in America since 2002, when she came to New York on student visa, met a man from her hometown of Minsk, and applied for permanent residency.

Nine years later, Anna is living in St. Louis, raising a three-year-old daughter, Paulina, and working with an international resettlement agency. Of her famous surname, she tells me over the phone, “I don’t like to brag about it. I am proud of the fact that Yuri Gagarin is my relative, but even if he were not part of my family, I would be proud of what he did for humanity.” I ask whether Americans recognize her last name. “No, only Russians,” she replies. “Americans don’t know the name. They only know Lady Gaga.”

Before I leave Russia, I ask Galina what she thought motivated her father to go into space. “I think the dream,” she says. “The dream to fly. From the modern position, it may seem very strange, very unusual. But I can understand how a small boy from a very poor family could have such a powerful dream.” (I’m reminded of a line in Le Petit Prince: “Only children know what they are looking for.”)

When her father died, Galina had just turned seven. I ask her if, as a child, she understood the importance of what he did. “I remember that I asked Father if he wanted to go to space once more,” she says, smiling. “He told me that he wanted to very much. Very much.”

That, of course, never happened. Gagarin went only once around the planet, but it was enough to change the world forever. Every orbit since has been a tribute to the first.

Allen Abel, who grew up in New York City at the height of the Space Race, is the Washington, D.C. columnist for Canada’s National Post newspaper.