The Father of Chinese Aviation

Feng Ru made history on the California coast, then introduced airplanes to his native land.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/fengru-631.jpg)

At twilight on a Tuesday evening in September 1909, Feng Ru prepared to test an airplane of his own design above the gently rolling hills of Oakland, California. It was just six years after Orville and Wilbur Wright took to the skies at Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina, and only a year after their first public flights.

“The big bi-plane, with its four starting wheels tucked beneath it like the talons of a bird, sailed slowly in an elliptical course around the crest of the hill nearly back to the starting point,” reported the Oakland Enquirer in its September 23 edition. For an astonishing 20 minutes Feng circled the Piedmont area, never more than 12 feet off the ground. Suddenly, a bolt holding the propeller to the shaft snapped, sending Feng tumbling to earth, bruised but otherwise unharmed.

While Feng Ru is little known in the United States, his fame in China is equivalent to the Wright brothers’. Middle- and high schools are named in his honor, and his childhood home is a museum; China even considers its space program to be based upon the foundations of Feng’s work.

Feng immigrated to the U.S. from China sometime between 1894 and 1898, when he was in his early teens, and immediately set to work doing odd jobs at a Chinese mission in San Francisco. “He was staggered by America’s power and prosperity. He understood that industrialization made the country great, and felt that industrialization could do the same for China,” says historian Patti Gully, who has co-authored a book on the contributions of Chinese living outside their country to the development of aviation in China. “So he went east to learn all he could about machines, working in shipyards, power plants, machine shops, anywhere he could acquire mechanical knowledge.”

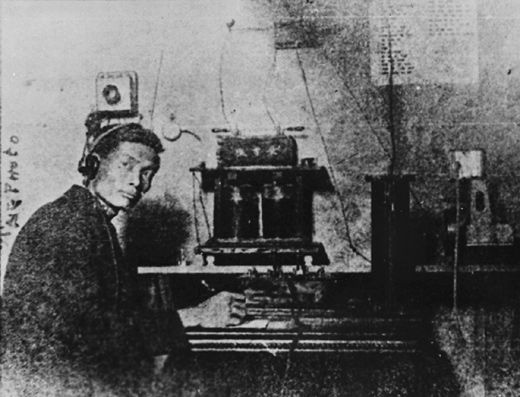

Feng became well known for developing alternate versions of the water pump, the generator, the telephone, and the wireless telegraph, some of which were used by San Francisco’s Chinese businessmen. But upon hearing of the Wright brothers’ success, Feng turned his attention to aviation, laboriously translating into Chinese anything he could find on the Wrights, Glenn Curtiss and, later, French aircraft designer Henri Farman.

By 1906, Feng decided to return to California to establish an aircraft factory, building airplanes of his own design. San Francisco’s massive earthquake and resulting fire forced him to relocate to Oakland instead, where, funded by local Chinese businessmen, Feng erected his workshop—a 10- by eight-foot shack. Jammed into this small space were tools, books, journals, mechanical projects, aircraft parts—and Feng himself, who rarely finished work before 3 a.m.

In this tiny spot, the self-taught engineer established the Guangdong Air Vehicle Company in 1909, and completed his first airplane that year, according to the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. During one test flight, Feng lost control of his airplane (not an unusual occurrence), which plunged into his workshop, setting it ablaze. Feng and his three assistants moved operations to an Oakland hayfield, referred to by the New York Times and the Washington Post as “a hidden retreat.”

“They posted guards at the perimeters of the field to discourage the curious,” says Gully, “and talked to visitors through a crack in the wall.”

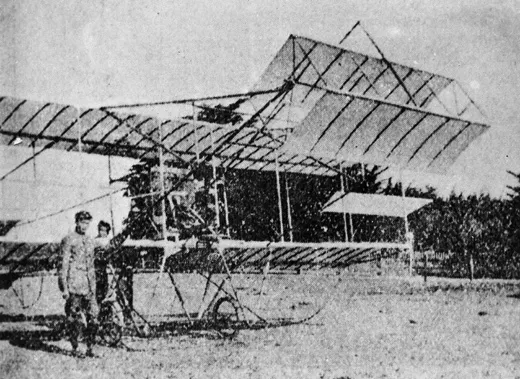

So anxious was Feng to keep his invention secret that he had the engine castings made by different East Coast machine shops, then assembled the parts himself. His discretion paid off; Feng’s successful test flights were covered by mainstream press, and his work was praised by revolutionary Sun Yat-sen. By 1911, as the New York Times reported on February 21: “[Feng] will leave here for his native land to-morrow, taking with him a biplane of the Curtiss type, in which he intends to make exhibition flights. It is believed that he will be the first aviator to rise from the ground in China…. The machine he is taking to China is of his own construction. The aviator is financed by six of his countrymen, residents of Oakland, who will accompany him on the trip. The first flights will be tried at Hongkong and Canton.”

Feng was leaving just in time: anti-Chinese sentiment was on the rise in the American West, and the Oregonian reported of the pilot’s latest flight: “Immigration officials and customs inspectors are today said to be gnashing their teeth. They find it hard enough to keep the Chinese out now, without having them dropping in on flying machines.”

When Feng arrived in Hong Kong on March 21, 1911, by custom he should have headed immediately toward his ancestral village to pay his respects. But even with his family urging him to come home, the preoccupied inventor was so obsessed with his airplane that it took him two months to fulfill his duties.

On August 26, 1912, Feng was killed while performing an aerial exhibition before a crowd of 1,000 spectators. “He was performing in a plane of his own design and manufacture,” says Gully. “He was flying at about 120 feet and had traveled about five miles before the accident. I’ve read a report that he put his machine into an extreme climb, but his engine seemed to fail and the aircraft fell to the ground. It sounds like a classic stall, but of course no one knew about such things in those days. His aircraft smashed into a bamboo grove, and his injuries included a pierced lung. As he lay dying, he reportedly told his assistants, ‘Your faith in the progress of your cause is by no means to be affected by my death.’”

The Republic of China gave Feng Ru a full military funeral, awarding him the posthumous rank of a major general. At Sun Yat-Sen’s request, the words “Chinese Aviation Pioneer” were engraved upon Feng’s tombstone.