The First U.S. Air Force Mission, 100 Years Ago

In the spring of 1916, a group of Army pilots went after Pancho Villa’s guerillas in Mexico.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e2/b5/e2b5f1d8-0344-4ae4-bb92-6af903e3d356/1st_aero_squadron_in_mexico.jpg)

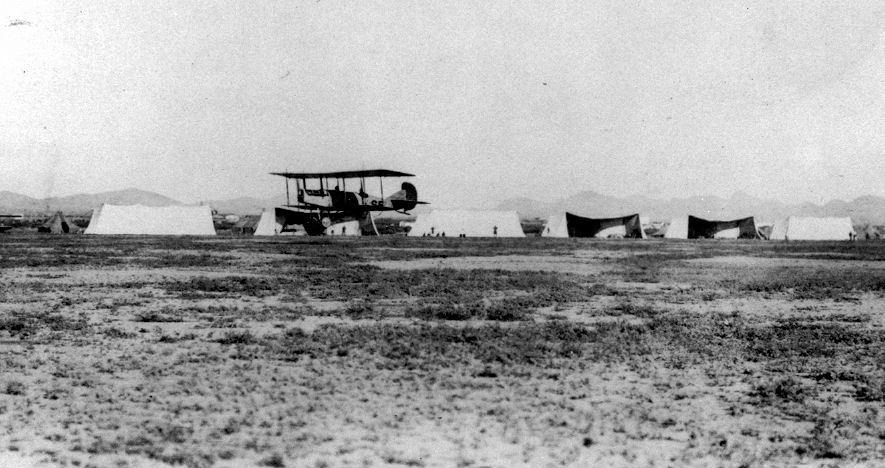

On March 19, 1916, eight Curtiss biplanes from the U.S. Army’s 1st Aero Squadron—the country’s entire air force—flew into Mexico for their first military action. The target was Pancho Villa, the guerilla leader who had provoked U.S. ire ten days earlier by crossing the border to attack the small town of Columbus, New Mexico. President Woodrow Wilson ordered General John “Black Jack” Pershing to chase Villa down, and to use airplanes (the Army had bought its first Wright Flyer just seven years earlier) as part of the so-called Punitive Expedition.

The 1st Aero Squadron went along strictly as aerial observers and messengers. The JN-3 biplanes weren’t even equipped with machine guns, although a few of the pilots did carry pistols and .22 rifles.

Let's just say that things didn't go very well. By the end of April, every one of the airplanes was destroyed. And it wasn't as if the squadron's commander, Capt. Benjamin Foulois, hadn't seen disaster coming. Back at the unit's home base in San Antonio, he had struggled with incessant equipment problems, locked in a battle with the Curtiss company over shoddy workmanship and parts that constantly needed replacing.

Now, flying 100 miles into Mexico after dusk on March 19, he faced another problem. Only one of his pilots had ever flown at night. Halfway to Pershing's camp the airplanes got separated, and cavalry had to be sent out looking for half of them. When the squadron flew its first reconnaissance flight a couple of days later, two airplanes were still missing and a third had already crashed after getting caught in a dust devil, stalling, and falling 50 feet to the ground.

On the first recon flight, Foulois and another pilot made it just 25 miles before getting tossed around by wicked up- and down-drafts in the 10,000-foot Sierra Madre mountains. They turned back.

And so it went. The squadron flew many successful missions over the next few weeks, scouting the enemy and delivering supplies and messages among Army units on the ground. But mostly, Foulois and crew fought just to keep their airplanes aloft, thwarted as they were by high-altitude flying, rough terrain, dust storms, engine troubles, and broken parts. One by one, the airplanes went out of service. On April 6, Capt. Townsend Dodd ran his into a ditch, destroying its landing gear. Lt. Ira Rader damaged his on April 14 coming down on rough ground. Three of the pilots barely escaped with their lives after landing on the outskirts of Chihuahua City, where an angry mob surrounded the planes and started burning holes in the cloth wings with cigarettes and cutting them with knives.

Despite all the mishaps, the Army learned a lot from the Mexican experience about how not to use its fledgling air force. When airmen were sent to join the fighting in France in 1917, they were far better equipped and better prepared. As Foulois wrote years later, "The work of the 1st Aero Squadron proved beyond dispute to the most hardened former soldier and congressman that aviation was no longer experimental or freakish."

Read a fuller account of the Punitive Expedition here.