The First Autolanding

Two pilots won a trophy in 1937 for keeping their hands off the controls.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/moments-and-milestones-aug-2012_FLASH.jpg)

The Army’s Fokker C-14B was a big, lumbering hulk of an open-cockpit transport with one huge parasol wing—mounted above the fuselage and not joined to it—and the beast could haul six passengers at a blistering maximum velocity of 137 mph. The lumbering speed may have been partially due to the C-14B having a single 525-horsepower Pratt & Whitney R-1690 on its nose. Other C-14 variants were powered by engines of higher power. But slow can be good; it’s certainly safer if you’re testing something and things go bad. When a small group of U.S. Army airmen needed a testbed to develop the first automatic landing system, they could not have found a more appropriate aircraft.

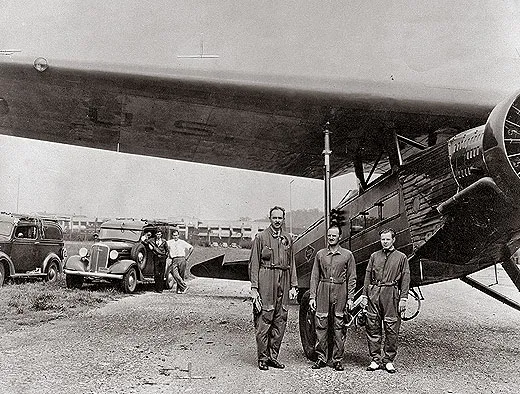

On August 23, 1937, at Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, two Army aviators, Captains Carl Crane and G.V. Holloman (for whom Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico was named), along with a civilian named Raymond Stout, took off in a C-14B that carried instruments and radios that Crane developed. Surrounding nearby Patterson Field were five radio beacons, and as receivers aboard the Fokker were turned on, the airplane began a descent and landing unaided by the crew. This, the first known successful demonstration of an automatic landing, won Crane and Holloman the Mackay Trophy for 1937, along with a Distinguished Flying Cross pinned on them by none other than Major General Hap Arnold.

Crane was a tall, cerebral, and quite formal gentleman who was born in San Antonio, Texas, in 1900. When he was 10, he witnessed famed Army aviator Benny Foulois fly from a field near Fort Sam Houston; he went on to have a lifelong career in aviation with an intense interest in “blind” flight—on instruments, with no visual contact with the ground. He earned a master’s degree in mechanical engineering, graduated from the Army’s pilot training center at Kelly Field in Texas, and later became a flight instructor. He found a kindred spirit in aviation pioneer William C. Ocker, a Pennsylvanian by birth and 20 years his senior. Ocker, also an Army aviator, became fascinated by instruments used for flying blind and developed new ones based on his own experiences. Together with Crane, he penned Blind Flight in Theory and Practice, published in 1932.

Crane’s autoland system (the term is a more modern usage) never encouraged the Army to pursue fully automatic landings, but the designer continued to study how sensory limitations prevent humans from relying on “seat of the pants” instincts to determine the attitude of an airplane. He learned early on that the inner ear is not up to the task of giving the pilot all the information needed. Pilots must not rely on their own sense of where they are in space, and must come to trust only the instruments. Crane and Ocker developed a training device that familiarized pilots with basic aircraft motion prior to the start of actual flying. Crane himself held more than 100 patents for various aircraft devices.

Autoland really came into its own in Europe. British European Airways ordered a fleet of Hawker Siddeley HS 121 Tridents, three-engine jetliners that in 1965 became the first transports to fly automatic landings in revenue service. Autoland has come a long way in 75 years.