The Flying Winnebago

For some reason the heli-camper never really caught on.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Oldies-Oddities-Heli-Home-FLASH.jpg)

Halfway through World War II, Igor Sikorsky wrote an article in The Atlantic that laid out a vision for postwar weekend travel. The future was rotorcraft, as in middle-class families owning a helicopter for country getaways. Four years later, Ruth and Latrobe Carroll published a children’s book, The Flying House, picturing an amphibious helicopter that could touch down in a forest glade or on a mountain lake. The Carrolls imagined their family copter with a porch, a shingled roof, sash windows, and a crooked stovepipe.

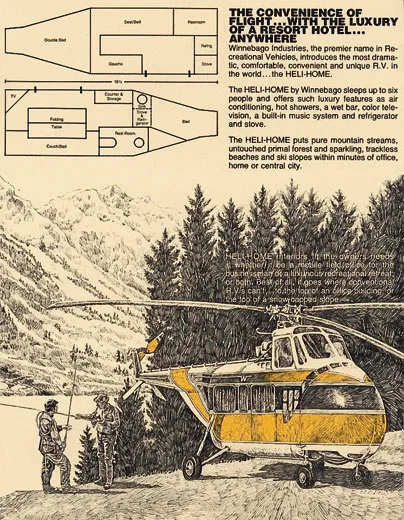

In the 1970s, the Itasca Division of Winnebago Industries actually built, certified, and sold the flying and floating Heli-Camper, advertised as “the most dramatic, comfortable, convenient and unique RV in the world.” (Floats were optional, though, and the porch was more of a screened awning that scrolled out for use with lawn chairs.) In the late 1970s, the lumbering offspring of a joint effort by Winnebago and Orlando Helicopter Airways, renamed Heli-Home, appeared on TV, starred in an RV trade show, and fluttered onto the pages of Time, Popular Mechanics, and Popular Science.

And there it parked. Fred Clark, now retired from Orlando, estimates that total flying-camper sales topped out at a half-dozen, possibly seven. But the Heli-Camper’s mission was more brand awareness than sales, and in that respect it succeeded. Parked among ground-bound RVs, it drew hordes to dealerships nationwide—no small achievement, given the pall that the 1970s oil crisis had cast over the customer base. As furnished by Winnebago, the larger model’s 115 carpeted square feet could sleep six passengers, and had an electric range, sink, fridge, couches, eight-track tape deck, television, generator, twin water heaters, parquet-topped dinette tables, mini-bar, air conditioner, furnace, shower, and bathroom with holding tanks.

The novelty also drew smaller crowds of the curious and prosperous to Orlando Helicopter’s office at the Sanford, Florida airport. Says Clark, now 79, tire kickers favored an executive-style arrangement, without the camping gear. Fewer furnishings meant more space for friends and relatives, and greater range.

Orlando specialized in buying surplus Sikorsky military transports at government auctions and refurbishing them. Most ex-military helicopters that retired from federal service during the Vietnam era were restricted to use by public service agencies or businesses that didn’t carry passengers, but Orlando helicopters came with a general-purpose certificate and thus were legal for passenger transport, medical evacuation, cropdusting, and hauling cargo.

One of Orlando’s most popular conversions was the Twin-Pack, an S-58 modified to run on two gas turbines instead of the more maintenance-intensive radial piston engine. The piston-powered Heli-Camper came in an 800-horsepower model, based on the S-55 transport, and a 1,525-hp model, based on the larger S-58. Because recreation was the goal, only clear-weather navigation equipment was standard. Frank Gilanelli, then a publicist for Winnebago, recalls that during one photography session, the pilot dropped down to read highway road signs for navigation.

Prices ranged from $185,000 to $300,000. Part-timers could rent one for $10,000 per week, plus the cost of pilot and fuel—at 75 gallons per hour.

Before his death in a 1985 airplane crash, Jerry Compton of Richvale, California, relished flying his S-55 Heli-Camper into the Sierra Nevada, says Clark. After passing through other hands, Compton’s machine came to rest at the Valiant Air Command Museum in Titusville, Florida. Today, Winnebago trimmings on N37788 have been replaced by U.S. Air Force livery.

Fred Clark’s son, Brad, runs Vertical Aviation Technologies, which sells a helicopter kit, the Hummingbird (see “Build-it-Yourself Helicopters,” Aug. 2010). At the VAT shop, in Sanford, Brad showed how the seats fold down and the cyclic and collective controls stow to yield a sleeping cabin for two. Clark may offer a foldout screened enclosure for that campground lifestyle.

James Chiles is the author of The God Machine: From Boomerangs to Black Hawks, the Story of the Helicopter (Bantam Dell, 2001).