Why Europe Wants its Own Satellite Navigation Program

The beginning of a new global navigation system, Galileo.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/galileo-inorbit-631.jpg)

What would it be like if the European Union collectively built a global satellite network, breaking the monopoly of the Global Positioning System, which unbeknown to most casual users is owned and operated by the U.S. military?

There would be a lot of meetings, like the Security Accreditation Board confab every four weeks, where any one of 17 member nations can butt in and tinker with project development. There would be duplication of effort, like building two identical control centers in Germany and Italy, mostly so both countries feel they are getting their money’s worth out of the program.

There would be complex cross-jurisdiction responsibility for different bits of the scheme, shifting between the European Commission (EC) in Brussels, the European Space Agency in Paris, and the Global Navigation Satellite System Supervisory Authority, which last August set up shop in Prague. And there would be embarrassing press leaks: The CEO of German aerospace contractor OHB-System lost his job when in 2011 WikiLeaks revealed his statement to U.S. diplomats that the project was a “stupid idea that primarily serves French interests.”

So far, that’s what the birth of Europe’s global navigation satellite system, called Galileo, has been like. By 2017, the EU promises, Galileo will be a system of 30 satellites, orbiting at an altitude of 23,600 kilometers (14,664 miles) and capable of locating any object on Earth with an accuracy within four meters (13 feet).

Christian Langenbach is a participant in this historic enterprise, as managing director of Spaceopal, a new German-Italian consortium that won a contract two years ago to provide Galileo’s ground support. For the former business professor and computer programmer, the work is as much diplomatic as scientific. “It takes a lot of time to harmonize everything,” he explains. “This is the EU, where all member states have a right to raise their voice.”

Conceived in the early 2000s, Galileo was at first going to be a public-private partnership, like a giant toll road in the sky. Under the European Commission’s supervision, banks and contractors would finance most of the deployment, hoping to recoup the costs by later charging for services. That model fell apart in 2007 when it became clear that the Pentagon did not mind the rest of the world using GPS for free.

Europe’s banks and contractors recalculated their arithmetic accordingly, and bailed. The EC rescued Galileo with funding from the Union’s communal budget, only to discover the original cost estimates were wildly optimistic. By 2010, the project was nine years behind schedule and three times over budget, with a projected 20-year cost to beleaguered EU taxpayers of €22.2 billion ($28.6 billion), according to Open Europe, a British independent think tank. (The Rand Corporation has estimated research, development, and launch costs for GPS so far at $21.5 billion.) A 2008 inquiry by the British House of Commons’ Transport Committee found Galileo to be “a textbook example of how not to run large-scale infrastructure projects.”

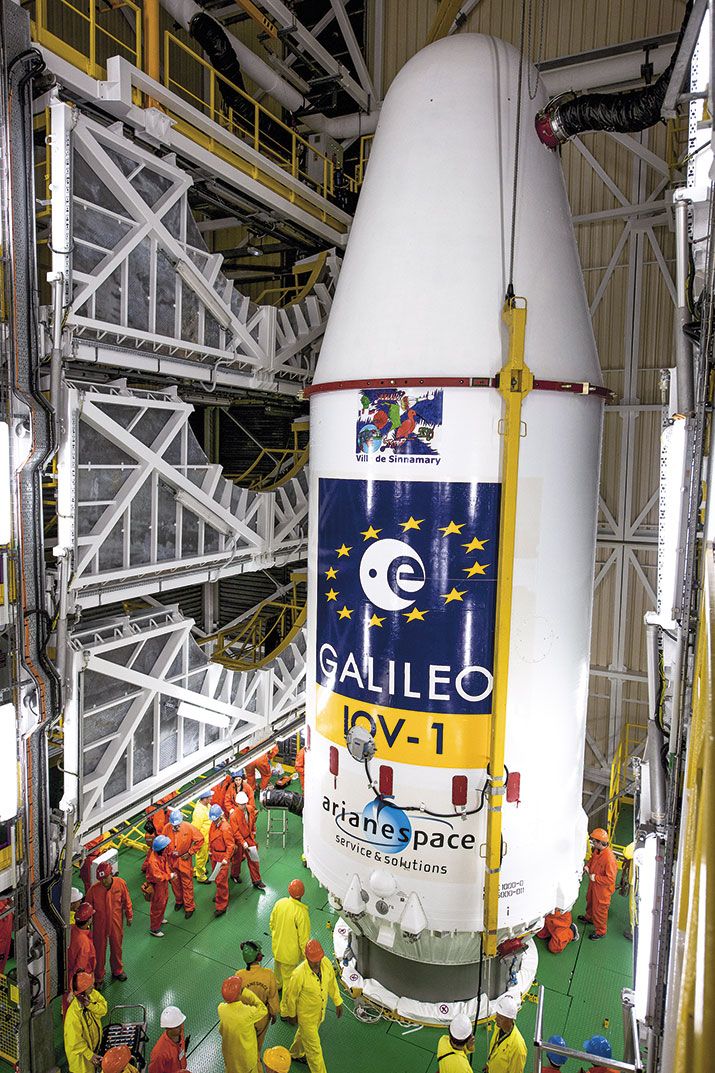

Yet like the European Union itself—whose aggregate economy remains the world’s largest—Galileo plods on, and is starting to gain momentum. From its spaceport in French Guiana, the European Space Agency launched the system’s first two satellites in 2011 on a Russian Soyuz rocket, then two more last October on another Soyuz. That kicked off the “in-orbit validation” phase of the project. Four satellites is enough to obtain a position fix and determine that the system is basically functional, explains Marco Falcone, an Italian who oversees some 150 ESA technicians working on Galileo at the agency’s operations center near Leyden in the Netherlands.

Once Galileo passes its orbital testing, the Europeans promise to go into overdrive, using an Ariane 5 on a series of launches to deploy four satellites at a time. By 2015, the schedule calls for 18 spacecraft. Working with GPS, that array will noticeably improve service for users on Earth, especially those hemmed in by tall buildings or navigating parts of the planet where GPS coverage is minimal, such as those close to the poles.

After Galileo goes live, satellite navigation services around the world will have an effective backup system in case the GPS breaks down or is hacked. And Europe, enthusiasts say, will finally control its own communications destiny, free at last of the unlikely but catastrophic threat that the U.S. Air Force might restrict GPS coverage in times of conflict. (Since it went fully operational in 1996, GPS has never been turned off.) That is a danger the EU can ill afford, with six percent of its gross domestic product already dependent on celestial navigation, says Antonio Tajani, the Union’s industry commissioner and current point man for Galileo. “The EU needs to ensure the continuity of services to its electricity grids, telecommunications networks, and stock exchanges,” the Italian-born Eurocrat says. “The proverbial ‘man in the street’ is likely not to be aware of this other side of satellite navigation, at least until things start going wrong.”

***

Through the years, Galileo, like most pan-European crusades, has been pushed along primarily by the continent’s core countries: France, Italy, and, with a bit more ambivalence, Germany. Despite the German executive’s dig at the French, Germany now seems to be winning the project’s best spoils. OHB-System itself, based in Bremen, will end up building most of the satellites, while ground operator Spaceopal is headquartered near Munich. The newer EU members, in Eastern Europe, have also been handed a stake in Galileo: Prague is the new home of the General Supervisory Authority, which will oversee the program for the EC as it gets bigger and more complex.

Britain, Europe’s perpetual sourpuss, is going along with EU integration but continues to grumble and criticize. Yet the first champion of Galileo, Neil Kinnock, was a British politician. A failed Labour candidate for prime minister in both 1987 and 1992, Kinnock moved to Brussels to become EC transport commissioner in 1995. There, he pushed the idea that the Union should not depend on America for future satellite-guided transportation. Kinnock unveiled the plans for Galileo in February 1999, with what turned out to be rose-tinted expectations on timing and cost. “The investment needed, less than 3 billion euros, is not unbearable since it would be spread between 15 member states over 10 years,” he said at the time. “The returns would be immense.”

But it was Kinnock’s successor as transport commissioner, Loyola de Palacio of Spain, and ESA director Antonio Rodota of Italy who in 2000 cut the ribbon on a Galileo program office. That year, a blue-ribbon commission chaired by Carl Bildt, a former Swedish prime minister, offered a clunkily phrased yet determined declaration of independence for European space exploration: “The driver of European space policy is to make Europe not dependent on non-European space infrastructure for any strategic and commercial applications.”

Other supporters touted the satellite network’s potential to spur job creation and technology spinoffs. The EU’s Directorate-General for Transport and Industry estimates that by 2025, 146,000 jobs will be created just in equipment sales—80,000 more than would be created by continuing to rely on GPS. Even Britain’s Department for Transport expects Galileo will bring in €74 billion in “economic and social benefits” over 20 years EU-wide.

In that spirit, Rodota got his ESA scientists busy sketching plans for the Galileo system. Planned on a similar scale to GPS, the network will have 24 satellites (the minimal number for global coverage) with six more as backups.

Galileo’s main difference from GPS is an orbital altitude 3,000 kilometers (1,864 miles) higher, which in turn points the satellites at a sharper angle back toward Earth: 56 degrees instead of 52. This will yield two benefits, project director Marco Falcone says: better coverage in “urban canyons,” where surrounding buildings can interfere with the GPS signal, and in the polar regions that European and other companies will increasingly be tapping for oil and other resources.

Galileo also aims to improve on GPS with a new kind of onboard clock powered by hydrogen laser technology. Very reliable clocks are essential: A deviation of one nanosecond—one-billionth of a second—per day translates to a 30-centimeter (12-inch) mistake in location, Falcone says. Galileo’s new clock will make the system more accurate than the current generation of GPS, which has a “worst case” margin of error of 7.8 meters (compared with Galileo’s four).

So far, the hydrogen laser clocks are working perfectly on the test satellites. That may be because funders threw politics aside to engage super-clockmaker Spectratime, whose Swiss facilities are outside the EU entirely. (Its parent company, Orolia, is French.) “The clocks were seen as quite high-risk, but they have turned out to be the least of the problems,” says Richard Peckham, a British executive with satellite maker Astrium.

***

The backroom struggle over a Galileo partnership—the public-private idea being backed by the capitalist-oriented north (Britain, Germany, and the Netherlands) but opposed by the Social Democratic south (France, Italy, and Spain)—was resolved by an unlikely party: the U.S. Department of Defense. Europe’s leaders were still struggling for consensus at the time of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Washington’s attitude abruptly hardened toward anything conceivably related to security, including a rival satellite network in the hands of its allies.

In December 2001, all 15 EU military ministries received a letter from Paul Wolfowitz, U.S. deputy secretary of defense, urging them to reconsider Galileo. The European network, he argued, could end up hogging spectrum that the U.S. military wanted for future GPS applications. That would “significantly complicate our ability to ensure availability of critical military GPS services in a time of crisis or conflict,” he wrote.

Wolfowitz went on to impugn the competence of mere civilians to mess with strategic satellite navigation technology. “I do not believe the current civil forum being used by the EC provides the proper venue to fully assess the security implications,” he wrote.

His missive backfired badly, rallying Europe around Galileo rather than scaring it off. French President Jacques Chirac, the continent’s most vocal critic of America’s post-9/11 policy, personally took up the cudgels for Galileo. The program, Chirac said, was essential to keep united Europe from becoming a “vassal” of the United States. It meant, he said, “we would not have to accept subjugation in space matters.”

Chirac was apparently so anxious to resist American arm-twisting that he agreed to the public-private partnership Galileo scheme that was championed by his British counterpart, Prime Minister Tony Blair. The council of EU transport ministers at last approved the satellite network in March 2002. The private sector was supposed to foot two-thirds of the bill.

***

But two valuable years, 2000 through 2002, had passed with Galileo stuck on the drawing board. And the intra-European skirmish over whether to go the partnership route turned out to be mere warm-up for the battle over which private contractors would participate, and on what terms. The heavy hitters of European aerospace—the United Kingdom’s Astrium and Inmarsat, France’s Alcatel and Thales, Hispasat and AENA of Spain, Finmeccanica of Italy—went into a lobbying frenzy, backed by their respective governments, that caused four years of planning gridlock, according to the Euro Parliament inquiry, as well as a similar study by the European Court of Auditors.

In 2006, the companies decided to form one master cartel to negotiate with the Eurocrats. But while Europe fiddled for half a decade, the world of satellite navigation had changed. Free GPS had made its way to millions of cars, computers, and mobile devices all over the world, including Europe. In 2007, the would-be private financiers walked away, and Galileo looked like it might crash and burn.

The collapse of the investor talks happened at a most inopportune time politically. The European Union drafts its joint Brussels-controlled budget only once every seven years, and 2007 marked the start of a new cycle. In theory, no new funds would be available until 2014. But the centralized European Commission bureaucracy sprang into action, shifting €3.4 billion from other programs so the Union could build its satellite network without private money.

As usual, Britain grumbled. The extra money from Brussels “made a mockery of the complex process of negotiations and compromises” that had gone before, Blair’s government complained, according to the Euro Parliament’s report. But the money remained committed, at least through 2013.

One good thing did come out of Galileo’s lost years: a healing of the rift with America over the project. Wolfowitz’s letter and Europe’s response led to “some adult discussions” between the two sides, recalls Peckham. The Pentagon decided it was possible after all for Galileo to operate without compromising America’s ability to wage war.

The Europeans, for their part, admitted Wolfowitz had not been completely off base when he fretted about a system planned by civilians with only minimal input from the military. According to the Open Europe report, over the years, Galileo’s original satellite design has required close to 1,000 security improvements. (The most important was probably parting ways with China, which was supposed to be a partner in Galileo. China instead has developed its own regional satellite navigation system, called Beidou; India and Japan are also building regional systems. Russia’s GLONASS is currently the only other global system.) “Security was immature in the early days,” Peckham observes.

In 2004, the United States and the European Union reached an agreement on divvying the satellite spectrum that will enable Galileo and GPS to supplement each other, offering a seamless, enhanced network to every user. Observers with concerns other than waging high-tech global war on behalf of the Pentagon now say Galileo will enhance satellite security. Not because it is more secure than GPS—the signals of both systems are weak by the time they reach Earth, so both systems are vulnerable to jamming by enemies. But experts predict that the redundancy will produce at least some strength. “The systems work in approximately the same way,” concluded a 2011 British Royal College of Engineering report. But “with the implementation of the European Galileo system, the resilience of the combined GPS/Galileo system will be considerably improved.”

Since its reorganization in 2007, Galileo seems to be working better. It now has a clear chain of command, sort of. The buck stops with, and the money is disbursed by, the European Commission and by the EU’s Tajani, who has called Galileo “the heart of our industrial policy.” The system will help the environment too, he says. “Satellite navigation is essential for achieving greater efficiencies in transport and agriculture. So in that sense too, Galileo will be at the heart of our efforts to create tomorrow’s low-carbon economy.”

Galileo’s budget woes are far from over. There is a struggle looming over the 2014 European Union budget, and over the question of whether Galileo will get enough cash to complete the whole satellite array. Tajani and the EC have proposed €7 billion to deploy and operate Galileo from 2014 to 2021, which they claim includes €500 million in savings pre-wrung from more efficient procurement practices. But the commissioner himself doubts that the member states will approve it all. “Times are hard,” Tajani says. “We need to advance strong arguments why this program should be further supported.”

Necessary or not, Galileo has put down strong enough roots over 13 years that it cannot be pulled up easily. Europe may yet realize its cherished dream of becoming a major player in the satellite navigation world.

Craig Mellow is a freelance writer in New York who reports frequently from Europe.