The Great Escape

For U.S. airmen trapped in Yugoslavia during World War II, building a secret airstrip was their only way out

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The-Great-Escape-FLASH.jpg)

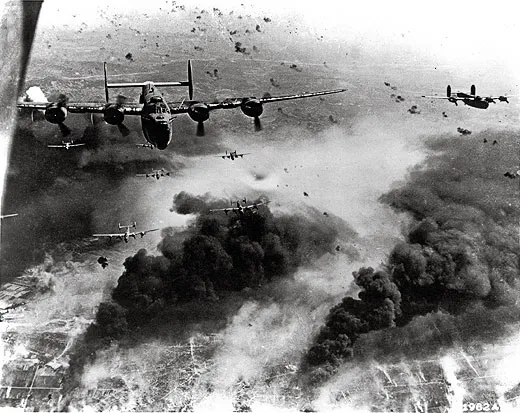

On Clare Musgrove’s first mission over Ploesti, Romania, he and the crew of his U.S. Army Air Forces bomber were certain to be shot at. Romania supplied the oil the Nazi war machine desperately needed for its tanks, trucks, and aircraft. While the Germans vowed to protect the flow of oil from Romanian wells at all costs, in 1943 and ’44, the Americans grew just as determined to choke production.

To do it, they sent Consolidated B-24 Liberators of the 15th Air Force, based in Bari, Italy. With a high wing, four engines, and an H-shape tail, a B-24 looks roomy from the outside, but half the crew—the pilots, navigator, bombardier, and radio operator—sit in or near the nose. Then comes the tightly packed bomb bay. “It usually had five 2,000-pound and ten 1,000-pound bombs,” says Musgrove. “It might have even carried some 500-pounds.” A narrow vertigo-inducing aluminum plank links the cockpit with the tail section, which housed two waist gunners, the tail gunner, and the ball-turret gunner, Musgrove’s position.

The ball turret was so cramped the gunner could not wear a parachute plus the head-to-toe leather flightsuit, which was the only protection from frostbite at altitude. So the gunner stowed his chute outside the turret, but within reach. If a bullet or chunk of flak cut a power line, the gunner had to hand-crank the turret to a position from which he could wriggle out of the escape hatch. “It was a very difficult place to remove yourself from, if you didn’t have power,” says Musgrove.

A hollow sphere of aluminum and glass, the ball turret could spin twin .50-caliber machine guns in an arc of 180-plus degrees. The turret hung more or less from the B-24’s belly, and the gunner inside operated it with electric controls mounted on pistol grips. The grips also carried triggers to fire the .50s.

During the summer of ’44, Musgrove, a gunnery instructor, volunteered to fly his 11th mission as a stand-in ball turret gunner. His departure from the 15th’s air base in Italy and flight over the Adriatic and into Yugoslavia were smooth. Over the target—part of Musgrove’s job was to see how well the crew hit it—flak took out two engines. The B-24 started losing altitude, and then a third engine died. Lieutenant Fred Tucker, the pilot, hit the alarm to abandon ship, and from the bomber’s smoky trail, parachutes blossomed.

All except Musgrove’s.

“I had to hand-crank the turret up and get out,” he says. “That took me a while. Then I couldn’t find my parachute, so that made me panic a bit.” The Germans spotted the other parachutes and rounded up all nine airmen. By the time Musgrove finally popped out of the B-24, his parachute opened miles away from the others. The Germans missed him—and they knew it.

DURING WORLD WAR II, that story played out on every front—a bomber went down, the enemy rounded up survivors. Often the airmen were attacked by shotgun- and pitchfork-wielding civilian mobs, driven to fury by relentless bombing raids; ironically, the airmen would be rescued by enemy soldiers. Where Musgrove went down in Yugoslavia, the opposite happened.

The Nazis had bombed and invaded the country on April 6, 1941, and the royalist government surrendered 11 days later. In the chaos that followed, two factions emerged: Marshal Josip Tito’s communist Partisans and General Draza Mihailovich’s royalist Chetniks. Numbering around 10,000, the Chetniks lived in mountainous western Serbia and followed the charismatic Mihailovich. He appeared on the May 25, 1942 cover of Time, which considered him one of Europe’s greatest guerrilla fighters. The magazine’s readers voted Mihailovich Man of the Year, though the editors picked Joseph Stalin. The Allies also went with Stalin instead of Mihailovich: A communist double agent convinced the British to align themselves with Stalin’s man, Tito, and the British convinced the Americans to do the same.

By 1944, when flak from Ploesti’s anti-aircraft artillery brought down Musgrove’s B-24, Tito and Mihailovich were fighting not only the Germans, but each other. The U.S. forces dropped supplies and weapons for Tito’s Partisans, while the Chetniks salvaged machine guns and ammunition from crashed B-24s and whatever food they could scrounge from the countryside and from the peasants who backed Mihailovich.

The U.S. Army Air Forces had instructed its airmen that if they had to bail out, they should do it over land controlled by Tito. But air crews in damaged aircraft rarely have a choice about where to jump. When airmen hit the silk over Serbia, “the Germans would jump in their trucks and tanks and chase their parachutes to the mountainside,” says Nick Petrovich, who grew up in Serbia and joined the Chetniks when he was 16. “We organized the peasants to pick up the guys, bury the parachute into the ground or into the hay so the Germans would not see it. Then we guerrillas would be taken by the peasants to where they hid those guys.”

WHILE HE FELL from the sky in 20 to 30 seconds, Musgrove spotted a flock of sheep to his left. “I said, ‘If I ever get on the ground, that’s where I’m going to head out, because sheep and humans go together,’ ” he recalls. When he landed, he tucked and rolled as he had learned during jump training. Then he found the two women and two boys herding the sheep. He cautiously revealed himself. Since he didn’t understand Serbian and they didn’t know English, everyone sat and stared at one another for a long time. Then the women and boys gathered the flock and started toward their village.

“I stood pat and didn’t know whether to follow them or not,” says Musgrove. “They turned around and motioned for me to follow them, and I did.” The peasant women led him to a house, and motioned for him to sit on the porch while villagers gathered around and talked. Then they brought him inside and motioned for him to sit at a table. “They were very generous,” he says. “They didn’t have much food for themselves, but they were willing to share it.”

While they ate, a quick rap came on the door. The man of the house answered and engaged in a deep conversation with the visitor. “He came back to the table, grabbed me by the shoulder, and took me into a bedroom and motioned for me to get under the bed,” says Musgrove. “Later that night another person came into the house, and they had another hefty conversation. He walked around the house. I could only see his boots—they looked like German boots to me—and the man of the house convinced him no one was in the house. He finally left, and I began to breathe somewhat easier.”

The next morning two Chetnik soldiers—neither of whom spoke English—arrived at the house, and they took Musgrove on a walk that lasted days. “I didn’t know anything about where we were going,” he says. “I didn’t know if I had been captured. I was scared to death. I didn’t speak the language. I was at the mercy of whatever person was helping me. Later in the week, we came upon a local man who was a schoolteacher who could speak some English, enough to tell me there was an assembly area where downed airmen were accumulating.”

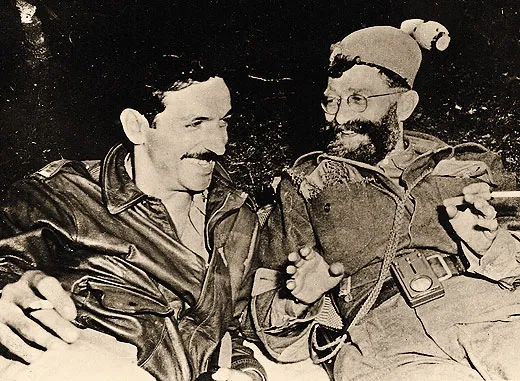

They walked farther. “The next day I met a man on horseback, and he could speak very good English,” says Musgrove. “He told me he was Captain George Musulin, who was in charge of the [U.S. Office of Strategic Services] group helping the Chetniks gather us to a central base, and they were going to build an airstrip and come in and fly us out.”

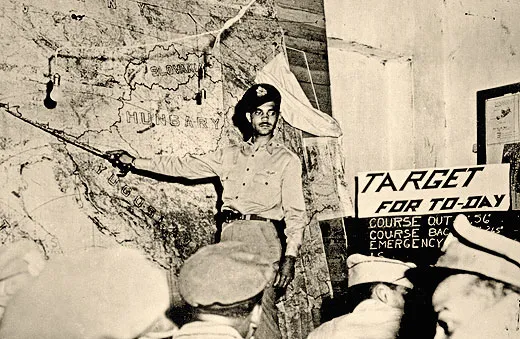

THE CHETNIKS HAD BEGUN their collection of U.S. airmen when the first one floated out of the sky following a disastrous low-level raid on Ploesti in 1943. A year later, the number of Americans under Chetnik care topped 100, but Army Air Forces officers did not realize there were so many and that they were clustered in Pranjani, a remote village in western Serbia. Air Force leaders figured that men not turned over by Tito’s Partisans had probably been rounded up by the Germans. That all changed after Musulin returned to the OSS station in Bari at the end of May 1944 after spending six months in Serbia gathering intelligence and organizing the Chetniks into resistance groups who could sabotage German targets, including bridges, ammunition depots, and airfields.

Musulin’s boss in Bari, George Vujnovich, had heard unconfirmed reports that the number of Allied airmen who had escaped capture by the Germans in Yugoslavia was substantial. When Musulin confirmed that there were at least 100 men in Chetnik territory, Vujnovich devised a rescue operation code-named Halyard. Vujnovich wanted to send in a three-man team headed by Musulin to supervise the building of an airfield from which U.S. airplanes could evacuate the airmen.

Arthur Jibilian, who had been a U.S. Navy radioman before joining the OSS, would be the team’s radio operator. Jibilian, better known as “Jibby,” was tasked with hauling around the heavy equipment needed to receive, transmit, and encode radio signals. According to Gregory A. Freeman, who wrote about Operation Halyard in his 2007 book, The Forgotten 500, Vujnovich felt even more urgency about launching the rescue after finding out that a few of the airmen in Pranjani had recently been sending encoded radio messages to the 15th Air Force headquarters in Bari asking for help.

In late July, the OSS sent the downed airmen a message to expect Musulin, Mike Rajacich, a Serbian-fluent OSS agent, and Jibby to jump on July 31 or the first clear night after.

Under a prior agreement between British and U.S. intelligence services, a British pilot and jumpmaster would fly the OSS team to the jump site in a U.S. aircraft. That night, after taking off from Fugia, Italy, in a C-47 painted black, they ran into anti-aircraft fire and turned back. The next night, the jumpmaster told them to leap into an area where the Halyard team could clearly see a battle raging. “It’s funny, yet it’s so serious it’s not funny,” said Jibby (interviewed for this story a few months before he died last March). Then the jumpmaster told the OSS team to parachute above a lake. According to Jibby, Musulin exploded and demanded—and got—a U.S. pilot and jumpmaster. “That night, we were in Yugoslavia,” said Jibby.

Jibby said he had been afraid during the two-hour flight to the drop zone, but the delays made him eager to jump. They used a static line and jumped at 800 feet with no emergency chute. Jibby hit the ground in 30 seconds. “It looked like I was going to come down into some trees, so I went into ‘tree position,’ ” he remembered. “I crossed my legs and put my elbows to my face.” Fortunately, he landed in a cornfield. “My best landing of all my parachuting,” he said. “Musulin landed on a chicken coop and crushed it all to hell. Mike, our third member, he landed in a tree with feet just barely off the ground and had to be helped out a bit.”

When the Halyard team finally met up with the downed fliers, they learned that the group had ballooned to 250. And they weren’t just showing up randomly. By then the Chetniks had developed precision tactics to rescue them: Once a parachute bloomed, one small guerrilla detachment rushed toward it, while a second larger group set up a perimeter, blocking roads with boulders or trees and placing .50-caliber machine guns at strategic points. “Most of the time the Germans would turn around and retreat,” Petrovich wrote in his 2003 autobiography, Freedom or Death, “but sometimes the expedition would include tanks and armored vehicles, and the only thing that we could do was to keep them under fire until the signal was received that the American crew had been evacuated.”

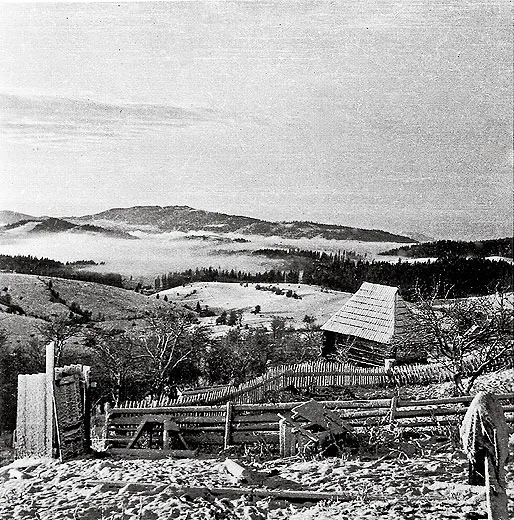

Right after one such mission on Zlatibor Mountain, Petrovich’s group received orders to move to Mihailovich’s headquarters at Ravna Gora. Once there, they were ordered 50 miles north to Pranjani, where the growing collection of U.S. airmen had discovered Galovica meadow. It was situated atop a hill and filled with boulders, but it was relatively flat, and the Halyard team thought it could accommodate C-47s.

“Basically it needed to be plowed flat and strengthened,” says Dik Daso, curator of modern military aircraft at the National Air and Space Museum. At night, with no machines, Allied airmen and Serbian peasants cleared boulders and filled in potholes. “Using ox wagons, the peasants would go to the nearby stream bed, get rock and sand, and bring the stuff up the hill to the runway site, in this never-ending daisy chain,” says Daso.

The airmen and Serbs completed the airstrip in nine days. On one end stood a forest, a sheer dropoff marked the other, and mountain peaks poked up a mere two miles ahead. The strip measured 150 feet wide and 2,100 feet long. Using that takeoff distance and loaded with enough fuel to return to Italy, a C-47 could haul out up to 25 airmen at a time.

The first evacuation was scheduled for the night of August 9.

As the sun set, everyone—the OSS team, the airmen, the Serbs who had taken them in, and the Serbs who had helped build the runway—gathered at the meadow. They lit flares and bonfires to outline the strip. At precisely 10 p.m., the first transport approached, a black C-47 with a white star on its tail. Its landing gear made contact too far down the runway, so the pilot applied power and pulled up. “We thought that was the end of the mission that night,” says Musgrove.

But the second pilot slammed down the gear of his C-47 and held the transport on the ground. The strip’s end approached. “He spun around on a wing, but didn’t damage the wing,” says Musgrove. “He bent it a little bit.” Fortunately, the transport was still airworthy. Three more C-47s landed without incident, including the one that had failed to stop on its first attempt.

The sickest dozen airmen were loaded first onto one of the aircraft. The pilot taxied into position on one engine, fired up the second, and, pressing the brakes, shoved the throttles forward. He released the brakes. Its engines screaming, the C-47 picked up speed. When it reached the end of the strip, it dropped below the hill and disappeared. But then, just like in the movies, it roared upward. Transports two, three, and four departed the same way.

Forty-eight men out, more than 200 to go.

Despite the success of the first airlift, Musulin and the other OSS leaders determined that trying to land in mountainous terrain at night was too dangerous. But conducting flight operations during the day had its own risks. Only 20 miles southeast of the Galovica meadow airfield was Cacak, a German garrison. “The Germans there were reduced in number, but they had an airfield and a few fighter planes,” said Jibby. In the end, the Halyard team decided that attacking Germans were the lesser of two evils.

At 8 a.m. the next day, Jibby heard the second round of transports—12 more C-47s—accompanied by the deep, throaty roar of fighters: one group of P-38s and another of P-51s. The -51s had red tails, the markings of the Tuskegee Airmen. “They came in numbers of six and 10, accompanying the guys landing on the mountain,” says Petrovich. “They would have a lot of fun flying around strafing German planes” parked on the ground at Cacak and at two other German garrisons nearby.

Airmen quickly filled the bare benches running the length of the C-47 cargo holds, and transport after transport pulled away. A couple hundred more men—in addition to the 248 who’d already been flown out— were evacuated on flights carried out over August 12, 15, and 18. The farewells between the airmen and the Serbs who had risked their lives helping them often brought tears from both sides, as well as last-minute gestures of goodwill. “The Chetniks and Serbians had very poor clothing and shoes,” says Musgrove. “They wore boots made out of felt, and things like that, so when we got on the plane we kicked our shoes off to them.”

“[The airmen] had these leather suits, and they would give us that to use,” says Petrovich. “The guys would give us their Colt pistols, which we loved very much.” In return, the Serbs gave the airmen homemade rugs, and one guerrilla handed airman Ray Weber his Chetnik cap. Weber was “a souvenir kind of guy,” says his daughter Sue Brown. Right after bailing out, Weber had started collecting mementos, tucking away a scrap of silk from his parachute, plus the ripcord.

Mihailovich asked if he could send two seriously ill Chetniks to Italy for medical attention, and Musulin felt he couldn’t refuse. When the men arrived in Bari, however, they were spotted by Tito’s Partisans, who reported them. “All hell broke loose,” said Jibby. “They were going to court-martial Musulin.” Cooler heads prevailed, but Musulin was ordered out and replaced with Nick Lalich for the rest of the operation.

Mihailovich told Lalich, the U.S.-born son of Serbian emigrants, that if the Air Force was interested, he could deliver more airmen to Pranjani. Jibby radioed the message back to the 15th’s headquarters, and received orders to continue Operation Halyard—with no promises to the Chetniks.

For a few more weeks, as soon as a few flights’ worth of airmen collected at Pranjani, Jibby called for more transports. The airstrip in the meadow operated almost like any other military airfield. “We didn’t do a couple of evacs because of bad weather,” said Jibby, “but I can’t say it was ever really a factor.” The OSS even flew in a doctor and two assistants to treat burns and flak wounds and set broken bones.

While waiting for their flight home, the airmen hid out and slept anywhere: On the ground near the strip, in villagers’ homes, in barns, atop fir needles in the nearby forest. The wounded always took priority, sleeping in beds while their hosts slept on the floor. Always, they were guarded by the Chetniks.

“Sometimes you would eat once a day,” said Jibby. “Sometimes twice or three times—sometimes you wouldn’t eat at all. You learned that you can overcome hunger. Keep going and after a while the hunger goes away. It hurts, but sooner or later, the host will come to you with a hunk of cheese and black bread with straw in it and you eat. Or chicken broth or beef broth with potatoes. Once in a while there would be a great celebration—they had chicken and lamb and we had a feast. Our stomachs would be shrunken so much we couldn’t eat much.”

The last flights out of Pranjani were in late August. “I have no knowledge that [the airfield] was used after the war except to graze the cattle,” says Petrovich. Life in the village returned to normal, while the Nazis suffered heavy losses in the east.

“[The Germans in Serbia] were demoralized,” says Petrovich. “They were in a strange country. They didn’t know if they were going to get home. Some would start crying, ‘I didn’t come here on my own volition,’ trying to justify themselves. At the beginning they were killing 100 Serbians for every German soldier killed, but when they became weakened and the garrisons depleted, then the whole game changed.”

At the end of 1944, the Soviets marched into Serbia. Two years later, Tito’s Partisans captured Mihailovich, accused him of collaborating with the Nazis, and executed him. The U.S. government downplayed protests by the rescued airmen in New York City and Washington, D.C. In 1948, the United States secretly and posthumously awarded Mihailovich the Legion of Merit, the highest U.S. commendation for a foreign citizen. “General Mihailovich and his forces,” it read in part, “although lacking adequate supplies and fighting under extreme hardship, contributed materially to the Allied cause, and were instrumental in obtaining a final Allied victory.”

When Mihailovich was captured, Petrovich and the other Chetniks were imprisoned and later forced to join the Partisans, but Petrovich escaped to Athens, Greece. “I was shot only three times and still alive and no airman was killed,” he says. “But the Nazis, Bosnian SS, and Croatian Nazis left their bones in the gorges and river beds.” Petrovich, now 83, lives in Mexico City.

In 2004, the Serbian government held a 60th anniversary reunion at the Pranjani strip to dedicate a plaque; two airmen, Clare Musgrove and Bob Wilson, made it. The next year, Mihailovich’s Legion of Merit was officially presented to his daughter, Gordana Mihailovich. Jibby was one of five Halyard veterans at the presentation. In July 2009, U.S. Congressman Bob Latta of Ohio introduced a bill to award Jibby the Medal of Honor for his actions during Operation Halyard. And last October 17, in a ceremony in New York City, 95-year-old George Vujnovich received the Bronze Star for his role in the rescue.

Souvenir collector Ray Weber left the military and built a tool-and-die business. “On June 11, we would have burnt toast and cottage cheese,” says his daughter Sue Brown. “It was symbolic of the day that he got shot down, and what he ate there most of the time—burnt bread and goat-cheese-something. But cottage cheese was the closest Mom could do to it.”

In 1955, Weber received a letter from one of the Serbian families he’d lived with while he was on the run. It was in Serbian, so Weber had it translated. The writer simply reminded Weber that he had hid with his family and asked how he was. Weber, who died in 1996, made copies of the letter and sent one to each member of his crew. His daughter doesn’t know if any of the men responded. The original letter, written on fading airmail paper, he saved in a box labeled “War Stuff.”

George Musulin, who died in 1987, worked with the OSS’s successor, the CIA, for a few years after the war. “My dad didn’t talk about the mission to his family directly, but we always heard it in conversation when he got together in social circles with our friends,” says daughter Joanne Esteban De La Riva. “Certainly I know it was a highlight of my dad’s life, that operation.”

Frequent contributor Phil Scott was blown away by his interviews with the survivors, and how casually they told their stories.