The Hunt for Houdini’s Airplane

Amateur detectives have found clues to the fate of the magician’s biplane.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Hunt-for-Houdini-631.jpg)

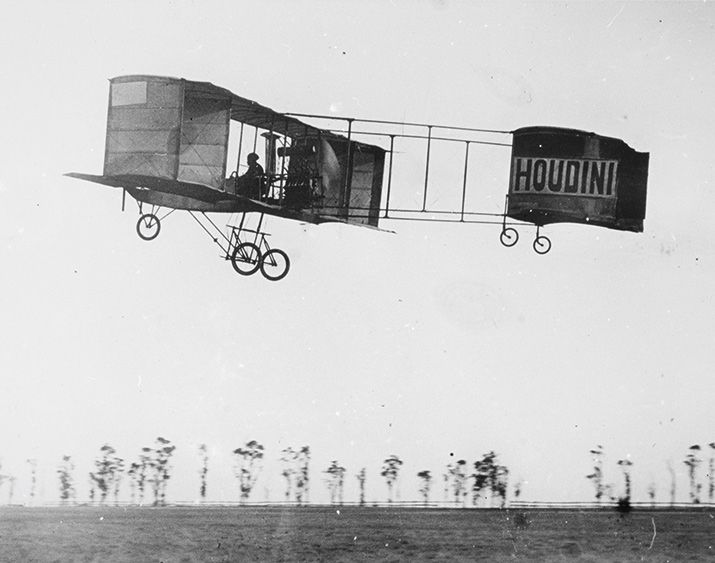

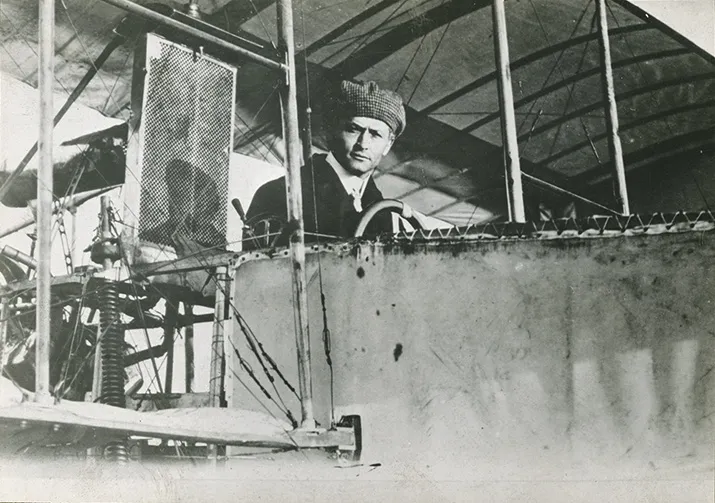

He wasn’t the first magician to attempt flight. As early as the 1800s, at least four others used balloon ascensions to stir up publicity. But Harry Houdini was the only illusionist to set a record recognized by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale: On March 18, 1910, he made the first heavier-than-air flight in Australia, taking off from Diggers Rest, a field roughly 20 miles from Melbourne.

He flew a Voisin biplane that he’d bought in Germany the year before. Powered by a British ENV engine capable of 60 to 80 horsepower, it sailed over trees, rocks, and fences, reported the Melbourne Argus, then wavered slightly. “Ah! Cabre, cabre!” shouted Antonio Brassac, Houdini’s French mechanic. “The word signifies the action of a rearing horse,” continued the Argus, “and it indicates that the plane, like the horse, will almost inevitably come to grief.”

Fortunately, it didn’t. For Houdini was competing against two other aviators for the record: Ralph Banks, a Melbourne garage owner who, using a Wright brothers airplane, was also attempting to make history at Diggers Rest. (Banks crashed during his March 1 attempt.) And near Sydney, about 500 miles away, 20-year-old Fred Custance claimed to have flown his Blériot monoplane on March 17, just one day earlier. (Without adequate documentation, the FAI rejected Custance’s claim.)

After making 18 flights in Australia, Houdini had the Voisin crated and shipped back to England. He planned to fly the airplane to each of his performances during his next U.K. tour, as a publicity stunt.

But Houdini never flew the airplane again. He remained interested in aviation for a few years, attending the 1911 International Air Meet in Chicago, where he met Orville Wright, Glenn Curtiss, and Lincoln Beachey. (The famous aviators thought Houdini was Australian, and wanted to know all about “his country.”)

So what happened to Houdini’s airplane?

In 2009, in preparation for the centennial of aviation in Australia, Melbourne council official Rob MacCay decided to find out. He set up a website organizing a search, and a loose-knit team of enthusiasts around the world began to hunt for clues, scouring books on Houdini’s life and investigating letters and diaries in private collections.

Jon Becker, who has spent more than 10 years looking for Houdini’s airplane, was one of the first to join MacCay’s team. Becker, president of Airborne Innovations (a Colorado-based company specializing in drone payloads), worked in Australia for five years, frequently driving by the site of Houdini’s historic flight.

“I’ve contacted a number of Houdini [memorabilia] collectors,” Becker says, “to see if by chance someone had some additional clue. Some were helpful, suggesting other leads if they had no information. Most had such large collections that fulfilling my request would require an on-site researcher.”

One of the first items to surface was a telegram Houdini had sent aviator John Moisant in 1910, offering his crated Voisin so that Moisant could compete in the Paris-to-London air race. (Moisant was in England, awaiting spare parts for his monoplane.) Moisant didn’t take Houdini up on his offer, finishing the race in his Blériot monoplane.

The next lead appeared in a 1913 letter from Houdini, giving his friend Donald Stevenson the airplane—if Stevenson agreed to pay several years’ worth of accumulated storage charges.

Stevenson designed stage props for a magician named William Robinson (stage name Chung Ling Soo), but he was also an aeronautical engineer who worked for British aviation legend Claude Grahame-White and various aviation firms.

In Houdini: A Pictorial Biography, author Milbourne Christopher writes that Stevenson sold Houdini’s Voisin “to another aviation enthusiast,” but doesn’t say who. And here the paper trail goes cold.

Professional magician Paul Zenon believes that Stevenson may have sold or given Houdini’s airplane to Robinson. Zenon was in Australia in 2009 when he first heard of Houdini’s 1910 flight, and he discovered that Stevenson and Robinson were business partners: “There are magazine adverts where they offer to take on engineering work in early aviation projects,” Zenon says. Robinson was killed on stage in 1918 when a stunt went wrong, and a warehouse filled with his props remained undisturbed until 1967. Did Robinson’s possessions contain Houdini’s crated Voisin?

Zenon is convinced that some part of Houdini’s aircraft remains. “I was in Australia a couple of days after the centenary,” he says, “and they had an airshow to commemorate the date. We were standing around at the airshow, chatting, and discussing that the likelihood of Houdini’s airplane still existing is small. As we were discussing this, a jeep drives up pulling a little trailer. And on that trailer was the engine and propeller from Fred Custance’s plane. It was the real thing. The fact that that plane isn’t famous and the propeller and motor still exist is quite interesting, you know?”

Contact us at A&[email protected] with any leads.

Rebecca Maksel is a senior associate editor at Air & Space/Smithsonian.