The Jet that Shocked the West

How the MiG-15 grounded the U.S. bomber fleet in Korea

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/MiG-opening-image-631.jpg)

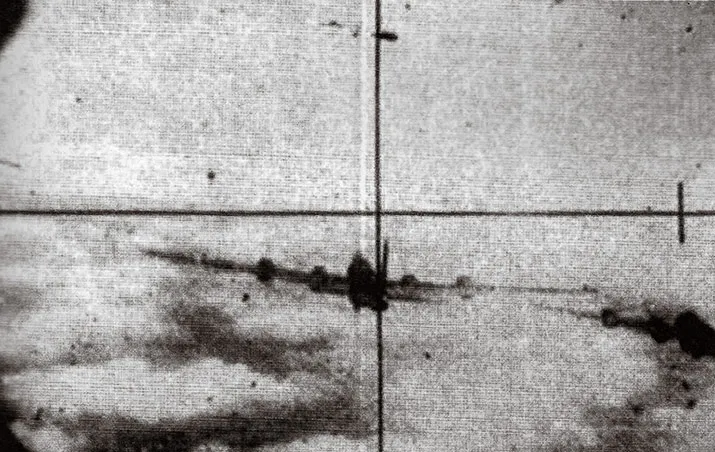

The Korean conflict was less than six months old on the morning of November 30, 1950, when a U.S. Air Force B-29 Superfortress, attacking an air base in North Korea, was lightly damaged by a fighter that overtook the bomber too fast for the attacker to be identified, much less for the Superfort’s gunner to fix it in the sights of his gun’s tracking system. Straight-wing Lockheed F-80 jets escorting the bomber made a token pursuit, but the accelerating fighter rapidly shrank to a dot, then disappeared.

The bomber crew’s reports sparked an organized panic that sizzled through the U.S. chain of command. Although the airmen’s description of the intruder matched no aircraft known to be operating in the theater, U.S. intelligence officials quickly made an educated assumption. The attacking aircraft was a MiG-15, most likely flying from a base in Manchuria. Before the incident, analysts believed that the only use Stalin had authorized for MiGs supporting communist China’s air force was protecting Shanghai from attack by nationalist Chinese bombers. The MiG was an ominous sign: China’s involvement in Korea was increasing, and Soviet technology was spreading.

For the crews strapping into the lumbering Superfortresses, the jets slashing through their formations became a source of suffocating dread. “I’ll tell you, everybody was scared,” says former B-29 pilot Earl McGill, as he describes the notable absence of radio chatter while he held his four-engine Boeing—the weapon system that had ended World War II—short of the runway for a mission against Namsi air base, near the border between North Korea and China. “On my first mission, we were briefed for heavy MiG interception. I was so scared on that day that I’ve never been frightened since, even when I flew combat missions in the B-52 [over Vietnam].” Earlier, the ready-room chatter had been filled with black humor. “The guy who briefed the navigation route had been an undertaker,” McGill says. He delivered the briefing in an undertaker’s stove-pipe hat.

On one disastrous day in October 1951—dubbed Black Tuesday—MiGs took out six of nine Superforts. McGill’s first encounter with the craft had been typically brief. “One of the gunners called him out. He was a small silhouette,” McGill says. “That’s when I saw him…. [The gunners] were shooting at him.” McGill says the bomber’s centrally controlled firing system provided some protection against the fighters.

MiG-15 pilot Porfiriy Ovsyannikov was on the other end of the B-29’s guns. “When they fired at us, they smoked, and you think, Is the bomber burning, or is it machine gun smoke?” he recalled in 2007, when Russian historians Oleg Korytov and Konstantin Chirkin interviewed him for an oral history of Soviet combat pilots who fought in World War II and Korea. (The interviews are posted on the website lend-lease.airforce.ru/english.) The historians asked Ovsyannikov to rate the B-29’s defensive weapons. His reply: “Very good.” But MiG pilots were able to open fire from about 2,000 feet away, and at that distance, says McGill, they could savage a B-29 formation.

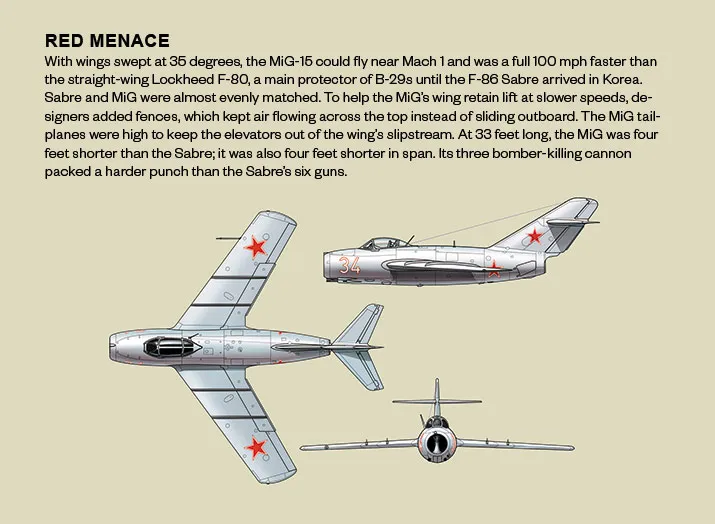

“The MiG-15 surprised the hell out of us,” says National Air and Space Museum curator Robert van der Linden. Compared to the North American F-86 Sabre, hastily introduced in combat after the MiGs showed up, “the MiG was faster, could outclimb it, and had more firepower,” he says. And Sabre pilots knew it.

“You’re damned right it was intimidating,” says retired Air Force Lieutenant General Charles “Chick” Cleveland, remembering his first encounter with a MiG-15. He was flying a Sabre with the 334th Fighter-Intercepter Squadron over Korea in 1952. Only weeks before, the squadron commander, high-scoring World War II ace George Andrew Davis, was killed by the Soviet fighter. (Davis was posthumously awarded a Medal of Honor.) Now, pulling a tight turn to evade the MiG, Cleveland violated the Sabre’s unforgiving stall margin, snapped over, and briefly entered a spin, as he puts it, “right there in the middle of combat.” Cleveland survived his mistake to become a Korean War ace with five confirmed MiG kills and two probables. Today, he’s president of the American Fighter Aces Association and still has respect for his adversary of 60 years ago. “Oh, it was a wonderful airplane,” he says from his home in Alabama. “You have to remember that the little MiG-15 in Korea was successful doing what all the Focke-Wulfs and Messerschmitts of World War II were never able to do: Drive the United States bomber force right out the sky.” From November 1951, B-29s stayed on the ground during the day; bombing missions were flown only at night.

Inevitably, the history of the MiG-15 returns to its dogfights with Sabres, the rivalry that has come to define the air war in Korea. But the link between MiG and Sabre began in the previous war. Both drew inspiration from the concept produced in the frantic search for a weapon at the end of World War II, when Allied aircraft had achieved numerical superiority over the German force. Desperate, the Luftwaffe High Command held a contest. The winning entry in “The Emergency Fighter Competition” was submitted by Focke-Wulf head designer Kurt Tank and designated TA-183; it was a concept for a single-engine jet with swept wings and a high T-tail. In 1945, British troops entered the Focke-Wulf facility in Bad Eilsen and confiscated plans, models, and wind tunnel data, which they quickly shared with the Americans. And when Berlin collapsed, Soviet forces sifted through the home office of the German Air Ministry and scored a complete set of TA-183 blueprints and a treasure trove of wing research. Less than two years later, and within weeks of each other, the United States and the Soviet Union introduced single-engine jet fighters with wings swept to 35 degrees, stubby fuselages, and T-tails. The two aircraft looked so much alike that in Korea, a few U.S. pilots too eager to bag a MiG mistakenly shot down Sabres.

Neither aircraft was a copy of Tank’s design. The raw aeronautical research, in combination with the limited availability of engines and the prevailing materials of the time, necessarily imposed the commonalities on the designs. The first jet to fly from the Mikoyan-Gurevich (MiG) Design Bureau in Moscow was a straight-wing fighter, the MiG-9. The -9’s rudimentary engines—twin BMW jet engines captured in Germany—fell short of the design bureau’s specs for the MiG-15, yet Moscow hardly possessed the expertise to build better ones. The first operational MiG-15s would instead be powered by Rolls-Royce Nene engines—marvelously innovated and cluelessly supplied by the British.

Keen to thaw Anglo-Soviet relations, British Prime Minister Clement Attlee invited Soviet scientists and engineers to the Rolls-Royce jet facility to learn how the superior British engines were made. Attlee further offered to license production to the USSR—after exacting a solemn promise that the engines would be utilized only for non-military purposes. The offer stunned the Americans, who protested loudly. And the Soviets? Russian aviation historian and Ukrainian native Ilya Grinberg says, “Stalin himself couldn’t believe it. He said, ‘Who in their right mind would sell anything like this to us?’ ” Grinberg, a professor of technology at the State University of New York at Buffalo, points out that the presence in the delegation of Artem Mikoyan himself—the “Mi” in MiG—should have been a tip-off to what in fact ensued: The Rolls-Royce samples shipped to the USSR in 1946 were promptly installed into MiG-15 prototypes and successfully flight-tested. By the time the fighter was ready for mass production, the Soviets had reverse-engineered the Nene; their copy was designated the Klimov RD-45. When the British objected to the violation of their licensing agreement, says Grinberg, “the Russians just told them ‘Look, we incorporated a few changes. Now it qualifies as our own original design.’ ”

But as in the case of post-war Soviet duplicates of western European autos, craftsmanship in the Soviet engine copies compared unfavorably to what went into the real thing. The time between the introduction of the Klimov engines and their failure was measured in hours. “Knowing the general state of the Soviet aviation industry at the time,” Grinberg says, “quality control throughout the entire MiG was not what you would expect in the west.” Materials for high-stress parts were substandard. Tolerances were not precise. Indeed, some performance problems on individual MiGs were traced to wings that didn’t exactly match. Grinberg describes a Russian archival photo of production line workers casually installing an engine in a first generation MiG-15. “How shall I say this?” he says, hesitantly. “It’s not exactly people wearing white overalls in a high-tech environment.”

By that time, however, another Soviet design bureau, led by designer Andrei Tupolev, had copied rivet-for-rivet two Boeing B-29s that during World War II had made emergency landings in Soviet territory. Grinberg says the precision in manufacturing required by the Tupolev project spread into the MiG program. In fact, “the project to duplicate the B-29 dragged not only the aviation industry but all Soviet industries up to a higher level,” he says. Though the MiG remained inexpensively built and unapologetically spartan, the finished product, which first flew on the last day of 1947, was rugged and reliable.

The first wave of F-86 pilots in the 4th Fighter-Interceptor Wing included veterans of World War II combat. Ostensibly, they were to engage inexperienced Russian-trained Chinese MiG-15 pilots. But it soon became clear the North Korean MiGs weren’t flown by recent flight school grads. The Sabre jocks called the mystery pilots honchos, Japanese for “bosses.” Today, we know most of the North Korean-marked MiG-15s were piloted by battle-hardened fliers of the Soviet air force.

Chick Cleveland describes an encounter with a MiG pilot whose skills suggested more than classroom training. Cleveland was approaching the Yalu River at 35,000 feet when the MiG came fast, head-on. Both aircraft were flying at their Mach limits as they passed one another. “I told myself, ‘This isn’t practice anymore, this is for real.’ ” Exploiting the Sabre’s superior speed and turning radius, he broke off and gained position on the MiG’s tail. “I slid in so close behind him he looked like he was sitting in the living room with me.”

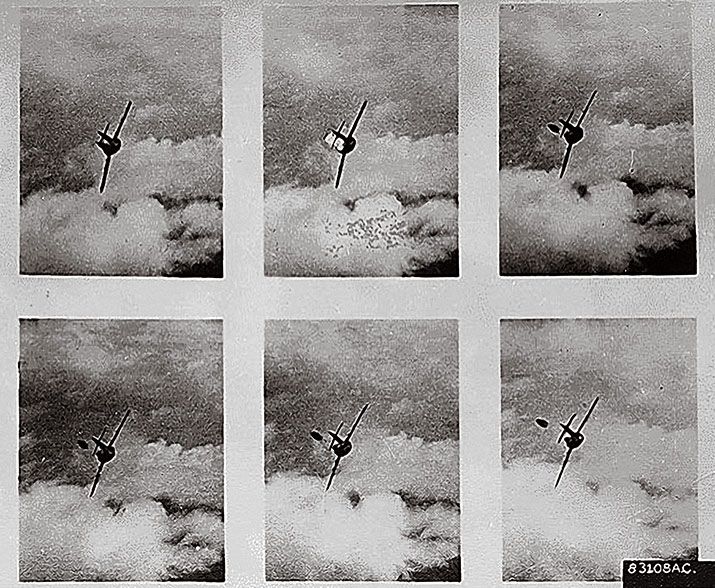

Flashing on stories of World War II pilots who, in the heat of dogfights, forgot to turn on their gun switch, Cleveland glanced down for an instant to verify the Sabre’s switch setting. “When I looked back up, that MiG was GONE, man. He was just not there.” Cleveland checked front and back “and all over the sky”—nothing. Only one chilling possibility remained. “I rolled the F-86 and, sure enough, there he was, right underneath me.” It was a deft attempt at role reversal, executed by the MiG pilot yanking back the throttle and pulling out the speed brakes to drop beneath, then behind, a tailgating adversary. “I was about to become the fox and he was turning into the hound,” Cleveland laughs. After several rolls in the Sabre, however, he reestablished his position on the tail of the Russian fighter, which resorted to “the classic MiG disengagement tactic,” a steep climb. Cleveland riddled the tailpipe and fuselage with 50-caliber rounds and the MiG rolled slowly to the left, nosed over, and plunged earthward. Given the MiG’s flight characteristics, a high-speed dive was a crash, not an escape strategy.

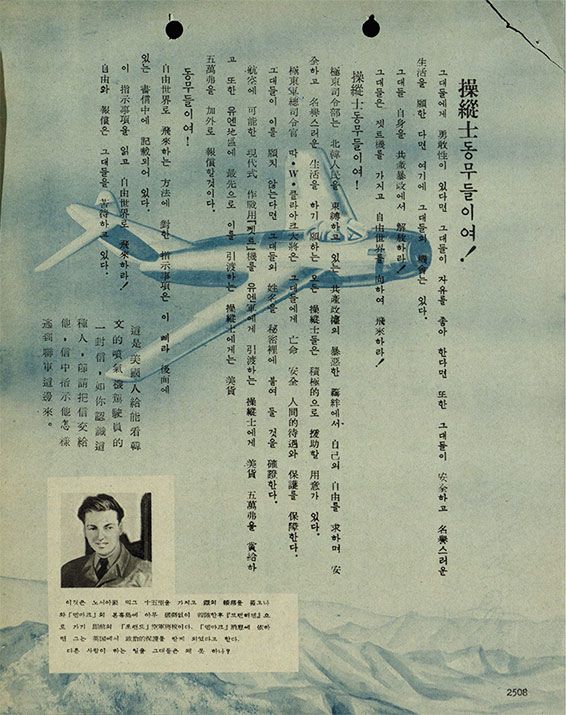

With the MiG challenging U.S. air superiority, Americans worked hard to get their hands on the Soviet technology, but they wouldn’t obtain a flyable MiG-15 until September 1953, when defecting North Korean pilot No Kum-Sok landed his jet at Kimpo Air Base, South Korea. Flying the Korean MiG would fully reveal what U.S. pilots were up against. To evaluate the Soviet fighter, the best of the U.S. Air Force test pilots—Captain Harold “Tom” Collins of the Wright Field Flight Test Division and Major Charles “Chuck” Yeager—were sent to Kadena Air Base, Japan. On September 29, 1953, the first Western pilot took to the sky in the mysterious MiG. The flight revealed the expected formidable performance, but also the MiG’s more unpleasant characteristics. “The defector pilot told me that the MiG-15 airplane had a strong tendency to spin out of accelerated, or even one ‘G,’ stalls and, often, it did not recover from the spin,” said Collins in 1991 for Test Flying at Old Wright Field, a collection of memoirs. “A white stripe was painted vertically down the instrument panel to be used to center the control stick when attempting spin recovery. He said that he had seen his instructor spin-in and killed.”

The flight tests revealed that the MiG’s speed was limited to .92 Mach. Above that, the aircraft’s flight controls were ineffective in dives or tight turns. During air-to-air combat in Korea, U.S. pilots witnessed MiG‑15s that were flirting with design limits suddenly enter dramatic, high-speed stalls, then snap end over end, frequently losing wings or tails.

Soviet MiG pilots were as well versed in the Sabre’s capabilities as American pilots were in the MiG’s. “There is no way to make me fight them in sustained turns,” said Soviet MiG-15 pilot Vladimir Zabelin for an oral history, translated in 2007. “Then he easily would have made it to my tail. When I made it to their tails, they knew that their only escape was in horizontal maneuvers…. I usually chased them from behind and a bit below…. When he began to roll, I tried to intercept him. If I did not shoot him down during his first one third of a turn, I had to abort the attack and zoom away.”

The Finnish air force bought MiG‑21 fighters from the Soviet Union in 1962, and also acquired four MiG‑15 trainers to acquaint pilots with the exotica of MiG cockpits. Retired Finnish test pilot Colonel Jyrki Laukkanen found the MiG-15 responsive and maneuverable, “once you knew its limitations and stayed within the safe envelope. Basically, you had to remain below .9 Mach and above 162 knots [186 mph]; otherwise you began to lose controllability.” Landings could be touchy, due to manually pumped pneumatic brakes that faded fast. “If they warmed up, you had no steering or stopping capability other than to shut down the engine and watch where you ended up—usually on the grass.”

Laukkanen says there were eccentricities in the MiG-15 cockpit. “The artificial horizon in the MiG-15 was curious.” The upper part of the gauge normally representing the sky was brown, while the lower part that was usually the ground was sky-blue. The gauge was designed so, when climbing, the aircraft symbol moved downward. “It acted like it was assembled inverted,” Laukkanen marvels. “Yet it was not.” The fuel gauges in the MiG-15 he also found “especially unreliable,” so Finnish pilots learned to estimate remaining fuel by watching the clock. As chief test pilot, Laukkanen accumulated more than 1,200 hours in the delta-wing MiG-21. (He is also the only Finn to solo in a P-51 Mustang.) “For me, the MiG-15 held no special mystique,” he says. “My favorite airplane, which I unfortunately never had a chance to fly, was the F-86 Sabre.”

A more objective measure of the relative strengths of MiG and Sabre are the number of enemy aircraft each shot down, but these kill ratios have been hard to pin down. At the end of the Korean War, for example, Chick Cleveland was credited with four MiG-15 kills, two probable kills, and four damaged MiGs. The MiG he last saw in a high-speed death dive? “My wingman and I followed him as he went straight down and into a cloud deck at a couple of thousand feet. I know damn well he didn’t make it. But because we didn’t see him eject or the plane actually hit the ground, it was listed as a probable instead.” After exhaustive research by a fellow Sabre pilot over a half-century later, his second “probable” MiG would finally be changed to a verified kill by the Air Force Board for Correction of Military Records. In 2008 Cleveland belatedly became America’s newest named ace.

The Soviet method of establishing claims, according to Porfiriy Ovsyannikov, was less involved. “We made the attack, came home, landed, and I reported,” he said. “We fought an engagement! I attacked four B-29s. That was it. In addition, the enemy spoke freely and put out over the radio: ‘At such-and-such location, our bombers were attacked by MiG-15 aircraft. As a result, one aircraft fell into the ocean. A second aircraft was damaged and crashed upon landing on Okinawa.’ Then our gun-camera film was developed, and we looked at it. It showed me opening fire at very close range. And the others—some did and some did not. I got credit, that’s it.’ ”

Immediately following the war, the claims of Sabre superiority were overstated. Against 792 claimed MiG kills, the U.S. Air Force officially conceded just 58 Sabre losses. The Soviets, in turn, admitted MiG losses of around 350, yet have always claimed to have downed an improbable 640 F-86s—a figure that represents a majority of the entire deployment of Sabres to Korea. “All I can tell you is the Russians are damned liars,” says Sabre pilot Cleveland. “At least, in this instance they are.”

In the 1970s, an Air Force study called “Sabre Measures Charlie” upped the Sabre losses directly attributed to MiG combat to 92, which cut the F-86 kill ratio to 7-to-1. Later, with the dissolution of the USSR, the archives of the Soviet air force became available to scholars, whose studies have since pegged Soviet MiG-15 losses in Korea at 315.

Limiting the statistics to specific periods highlights more meaningful conclusions. Author and retired Air Force Colonel Doug Dildy observes that when Chinese, North Korean, and newly deployed Soviet pilots occupied the MiG-15 cockpit, statistics do in fact support a 9-to-1 Sabre-favoring kill ratio. However, when claimed kills are restricted to a span encompassing 1951 combat, when Americans faced Soviet pilots who flew against the Luftwaffe during the Great Patriotic War, the kill ratio flattens out to a nearly dead-even 1.4 to 1, slightly favoring the Sabre.

The pattern of the air war in Korea gives credence to this interpretation. Once the honchos were rotated back to the Soviet Union, the less experienced Soviet replacements proved no match for the F-86 pilots. The Chinese lost fully one-quarter of their first generation MiG-15s to the evolved version of the Sabre, prompting Mao Tse Tung to suspend MiG missions for a month. The Chinese took delivery of the advanced MiG-15bis in the summer of 1953, but by then a cease-fire was about to be signed. The MiG-15 was quickly superseded by the MiG-17, which incorporated a wish list of improvements, mostly by cloning the technology found in two salvaged F-86 Sabres.

By the spring of 1953, the remaining Soviet MiG-15 pilots in Korea began avoiding engagement with U.S. aircraft. Stalin was dead, a cease-fire at Panmunjom appeared inevitable, and nobody wanted to be the last casualty. Ilya Grinberg sums up the attitude of the men in the cockpits of the capable fighter: “Soviet MiG-15 pilots viewed Korean air combat as simply a job to be done. After all, they weren’t fighting to protect the motherland. They viewed the Americans as adversaries, but not really enemies.”

While the star of the Mikoyan-Gurevich design bureau was making a name for itself in the West, the Soviet citizenry barely knew what that name was. The F-86 Sabre became an icon of American air superiority in 1950s popular culture, written into movie scripts, depicted on magazine covers, and silk-screened on metal school lunchboxes. During those years, however, the MiG-15 remained an enigma to the Soviet public. “We didn’t even know its designated name until way, way, later than you might think,” Grinberg says. “In any Russian aviation magazine, you might see images of the MiG-15, but the captions would always say simply ‘Modern Fighter Jet.’ ”

In the mid-1960s, in one of the inexplicable reversals that typified Soviet bureaucracy, the fighter was abruptly brought out of cover—and into public parks. “I remember vividly when they put a MiG-15 in our local park,” Grinberg says. The aircraft wasn’t installed on a pedestal or as part of a monument, as many are now, but simply towed into the park and wheels chocked. “I recall very well being so excited to go see the famous MiG. All us kids were climbing all over it, admiring the cockpit and all the instruments.”

A decade earlier, among the air forces of Warsaw Pact countries and others in Africa and the Middle East, word of the MiG-15’s performance in Korea spread. Eventually it served with the air forces of 35 nations.

MiG! Frequent contributor Stephen Joiner writes about aviation from his home in southern California. In this issue, he also reviewed a book about NASA’s X-15 rocketplane.