The Lodi Rocket Rebels

In a model rocketry contest, New Jersey high school students launch an egg — and something more.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The_Lodi_Rocket_Rebels_11-01-11_11_FLASH.jpg)

With a National meet just three days away, this afternoon is the last chance that members of the Lodi High School rocket club have to test their rocket designs. The team has set up a launch pad in the wilds of New Jersey, in a field lousy with gopher holes, corn stalks, and ticks. A field where Joe Fusco, the club’s mentor, has hunted for 10 years. A field near nothing, other than a small airport with the occasional airplane flying in and out.

Over long-sleeve shirts, the kids wear dark blue T-shirts sporting the team logo: a jawless skull, two rockets, and “Lodi Rocket Rebels”—all in yellow. Fusco has warned everyone to tie down their pant leg openings with rubber bands. “Look at that,” he says to a thin girl wearing ankle socks. “I told everyone to wear long socks.”

“Fusco [none of the Rebels uses “Mister” to address him], I always wear ankle socks,” says the girl. “Even in winter.”

Fusco, 54, raises his voice a lot, spewing gibes in a New Jersey accent like Tony Soprano’s. And like Soprano’s made men, every Rebel has a nickname. The girl he lectured about socks—Annmarie—he calls “Splash.” Ishani, who towers over Fusco, is “Lil’ Zilla.” There’s Aditi, or “ABC Aditi.” Isabella and her older brother Cristian (who gets annoyed when someone says they look like twins)—they’re “Cheeseburger and Fries.” Fusco calls Fatma “Little T” because her older sister, a recent graduate, he labeled “Turk,” or “T.” Carla, a Peruvian with black hair and eyes and a perfect American accent, is “Carla” (not much originality there, Fusco). Anthony is “Santhony” because his refined sense of touch allows him to sand any object to within a hair’s breadth. Fusco calls Ko Lung Chan, um, “Snookie” (for the record, Ko, a guy, looks nothing like Snookie from “Jersey Shore”). And there’s Joe. Though Joe calls himself “Magellan” (because he journeys everywhere during preparations for a launch), Fusco teasingly calls him “the Rocket King.”

Fusco turns his attention from sock length to the rockets, which are laid out on a rickety table. Built from scratch, they are similar in appearance: Newton, named after some famous physicist; Pete, one girl’s make-believe boyfriend; and a three-foot-tall, 2.5-inch-diameter finned rocket the team has christened Lucky “because we got good scores on that one,” says Fusco. Otherwise, he keeps mum on the specifics (no need to give the competition an advantage). During its last launch, not 15 minutes ago, Lucky’s capsule touched down 47 seconds after it left Earth—barely exceeding the all-important 45-second limit the national competition specifies.

The Lodi Rocket Rebels are one of 100 teams across the United States with a shot at winning the 2011 Team America Rocketry Challenge (TARC) at The Plains, Virginia, an hour outside of Washington, D.C. Sponsored by the Aerospace Industries Association (AIA) and the National Association of Rocketry, the challenge launched in 2002 as a one-time event to honor the 2003 centennial of the Wright brothers’ first powered flight. “Actually it started out as a social event to draw attention to our industry,” says Susan Lavrakas, AIA’s director of workforce development. “It was so popular with teachers and students, they kept asking when are we going to do this again, so it became an annual event.”

Since 2002, more than 50,000 students have entered. At the beginning of the 2010-11 school year, more than 600 teams applied, each team having three to 10 members from public and private schools, Boy and Girl Scouts, the Civil Air Patrol, church groups, and rocketry clubs. “They build a rocket, fly it, and send in their qualifying scores,” says Lavrakas. From those, TARC organizers chose the top 300 to demonstrate their rockets before a representative of the National Association of Rocketry, the oldest sport rocketry organization in the U.S. The top 100 scorers were invited to The Plains.

Going to Virginia means more than prestige, a great reference on a college application, and a shot at a share of the $75,000 in scholarships and prizes awarded to the top 10 teams. “Over the years, we look at it more closely as a tool for developing our workforce,” says Lavrakas. “We’re trying to make it a fun activity and prepare people to join the activity. Sponsors interacting with the kids—that will be a huge value.”

Or more concisely: “[The sponsors] know that 92 percent of the participants will go on to be engineers,” says student Joe.

To mix it up each year, challenge organizers change the rules. This year, for example, the rocket must weigh 1,000 grams (2.2 pounds) or less, and the weight limit for the solid fuel motor is 60 grams. The capsule carrying the payload—a raw egg that must land unbroken—must reach an altitude of 750 feet and deploy a 15-inch-diameter parachute. Total flight time must fall between 40 and 45 seconds. As long as they stay within those guidelines, and follow some minor engineering details about the solid-fuel motor, the teams are invited to go nuts.

“Of the 99 other entries, you’ll see 99 different designs,” says Joe. The Rebels’ Lucky looks like your typical ICBM: It’s computer-designed and honed with data gleaned from the Rebels’ weekend launches. In general, the team doesn’t launch rockets near the high school’s neighborhood, in part because of the noise and in part because rocket bodies or capsules occasionally go astray, requiring team members to borrow ladders and scamper on roofs.

While it’s a hot summer Wednesday at Fusco’s bug-infested hunting ground in Jersey, Saturday’s forecast for Virginia is for cool temperatures, which means the air will be more dense. Fusco and Joe loudly debate cutting a spill hole in Lucky’s parachute to make the rocket fall faster in the heavier air, while Joe whips out his multi-tool and, casually eyeballing it, starts slicing a hole in the chute’s center. By the time Fusco’s protest reaches a crescendo, it’s a done deal. Fusco rolls his eyes and sighs.

Time for final assembly. Little T lays the parachute on the table and folds it lengthwise into a rectangle. She then wraps the shroud lines around the chute and holds it up for Rebel approval. Aside from her normal job—recording all flight data and producing a graphical analysis of the flight—Little T always prepares the parachute. After her wrapping passes muster, the Rebels surround the rocket, fixing ballast, stuffing in wadding, and plunging the chutes down—their arms flailing like the Peanuts gang decorating the tree in “A Charlie Brown Christmas.”

They all step away right as one of the Rebels puts the final quarter twist on the capsule, attaching it to the rocket body. With great care, Joe picks the assembly off the table. A couple of others gently support either end, and they carry it to the gantry Joe built last summer. Joe lifts the rocket overhead, then slides it onto its rail. On the bare cardboard tube, someone has used a black Sharpie to write the name Lucky in small, swirling letters.

The Rebels wire the engine to the ignition, and Joe makes some minor adjustments. Then everyone backs away from the gantry.

At the mission control tables, Little T, ready to record data, stands next to Santhony, who’s sitting before the launch button. And just behind them there’s Fusco. They place a hold on the launch while a four-seat Piper Warrior comes in for a landing, then Carla starts shouting out the countdown at T minus 10 seconds. When she reaches “one,” Santhony presses the ignition, firing the solid-fuel engine.

Everyone with an iPhone handy presses the stopwatch function. Lucky whooshes skyward, spewing a trail of white smoke until the motor shuts down. After the nose cone jettisons from the body, the two sections continue upward for a few seconds, deploying their parachutes between the Rebels and the noon sun.

Everyone except Santhony shades their eyes and searches the sky. Like outfielders, three Rebels back up across the corn stubble to stay under the two components. A crosswind catches the pieces, forcing the Rebel outfielders to turn and pursue. As the capsule nears the ground, Carla starts yelling the total elapsed time: 40 seconds…41…42…the capsule settles into the corn stubble at 43 seconds! Yes!

Dodging gopher holes, Ko reaches it first, and holds it to his ear to listen to the TARC-approved altimeter. It beeps seven times—“Seven hundred,” Ko yells. After a pause, the altimeter beeps another five times—“Fifty feet,” he yells. Then it beeps three more times—“Three feet! Seven hundred fifty-three feet!” TARC rules state that rockets are awarded a point based on the number of feet over or under the assigned altitude, plus a point for every second of flight below 40 and above 45. The lowest number wins. With that altitude and flight duration, Lucky would score a 3 in competition at The Plains.

Not entirely satisfied, the Rebels want to launch Newton or Pete, and they excitedly plead their case. Fusco waits for them to settle down, then says: “Let’s pack up. We know this guy can dance.”

“You mean fly?” says Joe. Fusco rolls his eyes.

As they pack up the equipment, the girls chatter about guys. Fusco calls the club the “dating service for nerds,” and lectures team members on the best way to load the van. Once they’re onboard, the two-hour ride back to Lodi begins with the kids harassing Joe for ripping the fins off a rocket that earlier in the season had landed tail-first in mud. Fusco jumps in.

Little T repeatedly asks Fusco if they can stop at Taco Bell for dinner. “No!” barks Fusco. “We’re driving straight through.”

On Friday, the day before the meet, the local Harley-Davidson motorcycle club escorted a city rec center van, packed to the gills with Rebels, luggage, and rockets, out of Lodi. Five hours later, the van rolled up the driveway of Great Meadow, a lush steeplechase field outside of The Plains, where the Team America Rocketry Challenge is held.

TARC has a convention-like atmosphere suitable for teenage rocket buffs. In between launches, contestants can wander an ad-hoc mall and fly an F-35 flight simulator, play Aerospace Jeopardy, buy souvenir T-shirts and mugs, and collect gimme pens, caps, sunglasses, temporary tattoos, Frisbees, and foam yard darts, courtesy of NASA, the Department of Defense, and 34 companies that are members of the AIA—all event sponsors this year.

The Rebels pitch their tent on the edge of the steeplechase grounds, and Friday night they crowd into a nearby hotel. At the tent the next day, Fusco makes an announcement: “I slept with Bryan last night.”

“You make it sound so wrong,” says Bryan. Tall and charismatic, Bryan Santos, whom Joe calls “the Rocket God,” now attends Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Daytona Beach, Florida. But he and two other members of the 2010 Rebels came back to watch the competition. “It’s your second life behind school,” says Bryan. Joe hangs on his every word. “Last year [Fusco and Bryan] fought about everything,” says Joe. “In the end, they made a decision and compromised. I have taken his position almost.”

The rocket that Santos and last year’s team designed had to fly to 825 feet, and the egg payload had to descend on a streamer with a length-to-width ratio of five to one. Also—as they learned the day before the competition—the streamer could not be reinforced. “We [had] put scotch tape on the border to keep it from tearing,” says Joe. “That night in the hotel we stayed up all night going around each side of the streamer getting rid of the scotch tape, cutting it off. [The tapeless streamer] didn’t open. It kind of stuck together—it was a hot day, and humid. It opened I doubt 100 feet above the ground, and by then it had been declared ballistic and disqualified by the TARC officials.”

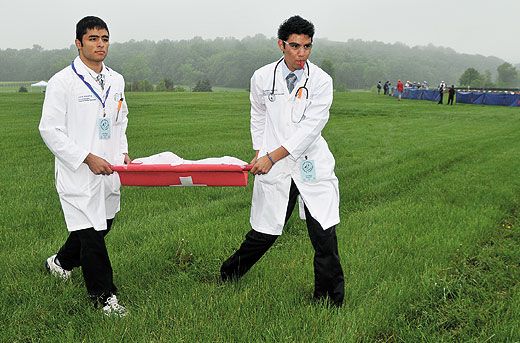

At Great Meadow, each team has been assigned an hour’s time slot for launching from one of seven pads. The Rebels’ hour starts at 11 a.m. They cross a broad grass field, lugging their gantry, rockets, computers, tools, and a stuffed-goose mascot to their assigned launch pad, Goddard II.

Wednesday’s rehearsal seems to have paid off: With each member performing the same job, the team launches Lucky without a hitch. Lucky’s flight time is right where it should be, but instead of gently arcing over at 750 feet, the rocket continues up for 24 more feet. “We were nailing it Wednesday,” says Fusco. “We don’t normally launch in the rain and heavy humidity; that’s why we went higher.” (Because moist air is thinner than dry air, there was less resistance to slow the rocket down and prevent it from going too high.)

In the final round, only the top 25 schools compete, and at the moment, the Rebels’ launch is good enough for a two-way tie for 24th place. But more rocket launches remain. The Lodi team has to wait it out at the tent. A couple of Rebels stay behind to monitor the leader board.

Joe is the first to report back. “Guys, the last four teams did not beat us,” he says before returning to the board.

“You know what—that’s respectable, tied for 24th,” says Fusco. One rocket explodes, and Fusco watches the pieces tumble to the ground. “It’s devastating to the team because they practiced and tested it,” he says solemnly. A female Rebel screams with delight.

After the last rocket has launched, Fusco walks with the team to the leader board. Contestants have jammed around it 10, 15 deep. Carla emerges from the wall of bodies and yells: “Fusco—we’re still tied for 24th place!” She races back into the pack, but returns crestfallen. Four rockets have tied for 19th place, forcing the Rebels out of the running.

“Guys, we didn’t make it,” she says. “We’re out, guys.” She holds her face in her hands and breaks down. Two other Rebels start weeping, and the eyes of another two well up. The guys look stricken while they try to comfort the girls and one another.

“We got work to do next year, buddy,” says Fusco to Joe.

The Rebels still scored high enough for the consolation prize: Numbers 26 through 30 can launch another one for the crowd, even though it won’t count. The team nixes it right away. “Can we still launch the goose?” asks Little T, choking back tears. She’s carrying the mascot stuffed inside her hoodie.

Glumly, the Rebels know they have to listen to the final launches, sit through the awards ceremony, eat dinner, then cram themselves inside the van for the long ride home. A few of the Rebels make noise about cutting out early, but Fusco retorts that being a good sport is the right thing to do.

“Fusco’s great—he helps keep it in perspective,” says Fran Rozman, the head of Lodi’s science department, who first approached Fusco to run the club. “The kids just love him, his personality.”

To kill time, the Rebels begin a Frisbee free-for-all outside their tent that evolves into batting practice incorporating the various foam gimme objects the team has collected. Watching the horseplay, Fusco blurts, “Guys, blame me.”

“Yeah,” says Joe. “You showed us too much love.”

Once the last rocket has launched, the intercom makes the come-to-the-formal-awards announcement. The ceremony features short speeches from an Obama administration bureaucrat, a legislator, and a U.S. serviceman. The Rebels drag themselves to the edge of the crowd and plop down in the grass to watch the top 10 teams get their due. As the winners are announced, the size of the prizes and scholarships grows, and so does the Lodi team’s despair.

Finally, the top three teams are revealed: Lambert High School from Suwanee, Georgia, and Harmony Magnet Academy from Strathmore, California, tie for third place. And the winner is…Rockwall-Heath High School in Heath, Texas.

“They’re just on cloud nine,” says Susan Votel, a Rockwall-Heath physics teacher and, for the last two years, the five-year-old club’s sponsor. In its first year, the team didn’t make nationals, and the last two years they’ve been stuck out of the money—in 12th place. “It’s just been several years in a row that they have placed well at the national competition,” says Votel. “This year they finally broke the spell.”

The team of four—president and senior John Easum (who started the club in eighth grade), seniors Michael Gerritsen and Colt McNally, and junior Landon Fisher—receives $10,500 in scholarships, and the club receives $1,000. They get to visit the White House and fly to Paris free to compete against the British and French teams. It’s a day Rockwell-Heath will never forget.

Neither will the Lodi Rocket Rebels. “This was their first year, and they got to go to Virginia,” says Fusco, leading the team’s exodus to the dinner tent before Rockwell-Heath finishes taking its bows. One Rebel observes that there’s a bright side to losing: They get to eat before the rush. Another Rebel boasts: “The only team from New Jersey and we placed 24th!”

Fusco has already set his sights on next year. “Move over, Snookie,” he says. “We are going to be the people from New Jersey that everyone is talking about.”

Phil Scott’s latest book is Then & Now: How Airplanes Got This Way.