The Million Mile Mission

A small band of believers urges NASA to take its next step—onto an asteroid.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/million-mile-mission-631.jpg)

It was another brilliantly sunny day for NASA astronaut Tom Jones. In orbit on his fourth space shuttle mission in February 2001, Jones was outside the International Space Station, installing a new laboratory module. He remembers the moment with great clarity: Gerhard Thiele, another astronaut, called from the ground to relay the news that the robotic NEAR Shoemaker probe had just made the first-ever landing on an asteroid, 433 Eros.

“There I was, turning bolts on the ISS,” says Jones. “I was thinking: What a cool job this is. But how much cooler would it be if I were doing this on an asteroid!”

The idea that astronauts might visit an asteroid and explore it up close had long intrigued him. Today, Jones is more convinced than ever that it would be a grand and worthwhile journey. “The asteroids,” he says, “are begging for a visit.”

By “the asteroids” he doesn’t mean one of the rocks circling out in the main belt between Mars and Jupiter, but something a lot closer to home: An Earth-crosser, or NEO (near-Earth object). A rogue.

Jones is part of an unofficial group of NASA actives and alums who have been studying, mostly on their own time, the particulars—engineering requirements, mission trajectories, scientific payoffs, and costs—of a human trip to an asteroid. Like the Mars Underground, a larger group of enthusiasts who for the past 20-plus years have been pushing for a voyage to Mars, the asteroid agitators are trying to build support for a mission. The two groups are far from mutually exclusive: Plenty of Mars Undergrounders share the desire to see Constellation, NASA’s human exploration program, send astronauts rock-hopping first.

The operational lessons learned from such an expedition would be crucial. “There’s no way a Mars program could take shape without a crewed mission to an asteroid,” says Jones. Aerospace engineer Robert Zubrin, who, as head of the international advocacy group the Mars Society, is one of the leading proponents of an expedition to the Red Planet, likes the logic of a shakedown flight to an asteroid. “I think it’s a valuable idea. It would help validate the Constellation hardware within a meaningful time frame,” he says. “Basically, it takes us farther out into space, and that’s good. Sort of like Columbus getting out there and saying, ‘There aren’t dragons out here after all.’ ”

Constellation’s primary destinations are the moon and Mars, but the asteroid hopefuls are lobbying to insert a third stop in the itinerary. For the record, NASA has no plans to send astronauts to a near-Earth object, and agency officials describe it as highly improbable given current budgets.

The Asteroid Underground is unfazed. According to Jones, “When you talk to an audience of taxpayers, they see the stepping stones: moon, asteroid, Mars.”

The idea of a mission to an asteroid is not new. In 1966, Eugene Smith, an engineer with Northrop Space Laboratories, conducted a study for NASA on the use of Apollo hardware, including the giant Saturn V rocket, to carry six astronauts on a flyby of Eros. The trip would have been scheduled for 1975, when the asteroid came within 13 million miles of Earth, more than 50 times the distance to the moon. The round trip would have been 500 days.

More recently, NEOs came to public attention in July 1994, when the comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 broke up and the pieces slammed into Jupiter, the largest packing a wallop equivalent to 400,000 times the power of the largest U.S. nuclear bomb ever exploded. Anyone who read a newspaper that summer imagined the same thing happening to Earth, and within two years an international organization called the Spaceguard Foundation was established to coordinate the tracking of asteroids and comets that might collide with the home planet.

Shoemaker-Levy got more people inside and outside NASA thinking seriously about the danger of NEOs. In October 2001, astronaut Ed Lu and astrophysicist Piet Hut convened a one-day workshop in Houston with about 20 asteroid and propulsion experts to discuss the possibility of deflecting an incoming NEO. Out of that meeting the B612 Foundation was formed, named for the space rock on which author Antoine de St. Exupéry’s Little Prince lived. The stated goal of the organization, now headed by Apollo veteran Rusty Schweickart, is to significantly alter the orbit of an asteroid in a controlled manner by 2015, just to show that it can be done.

Not by astronauts, though.

“I’m an old astronaut, so I’m totally for manned flights to an asteroid,” says Schweickart, who was Apollo 9’s lunar module pilot. “But in terms of deflecting one, robotic missions are completely adequate and far more cost-effective.”

The B612 Foundation proposes a rendezvous with a space rock for weeks or months, during which the robot spacecraft would act as a “gravity tractor,” using its own minuscule gravitational pull to tug the asteroid onto a new course. While B612 spread its message, Ed Lu went on to spend six months aboard the International Space Station. Three months after his return to Earth, in January 2004, the Bush administration announced its Vision for Space Exploration, an ambitious call to send astronauts beyond Earth orbit for the first time since 1972. While NASA set up Constellation and began focusing on the lunar return, targeted for 2020, Lu and the Asteroid Underground quietly pondered other possibilities.

“When NASA unveiled the concepts of the Ares I and V launch vehicles and [the] Orion [crew capsule],” remembers Lu, “I started wondering, ‘Hey, we have these rockets at our disposal. What else can we do?’ ”

By the summer of 2006, Lu, Tom Jones, and Dave Korsmeyer, an engineer at NASA’s Ames Research Center who specializes in celestial mechanics, were conferring regularly with more than a dozen colleagues around the country, asking about the capabilities of Constellation and writing papers. NASA agreed to fund a feasibility study through its Advanced Projects Office that would examine how to use the Orion and Ares hardware to send people to a near-Earth asteroid. Korsmeyer managed the group. After many phone calls and e-mails among the 17 members of the study team, the first meeting took place at the Johnson Space Center in Houston in August 2006. Subsequent gatherings, about one per month, were convened at various NASA centers around the country. By the end of the year, the group had come to the conclusion that NASA’s new hardware could in fact carry humans to a NEO.

“The first part of this study was to determine if we could make it to an asteroid with no modifications whatsoever to Orion and the launch vehicle,” says Korsmeyer. “But that would be pretty hard and hairy.”

The weight of the crew, plus all the water, food, oxygen, and other supplies needed for a long voyage, posed a huge constraint. So the study team reduced the crew from four people (the baseline for a lunar mission) to three or even two, which freed up room for supplies. The good news is that a six-month asteroid mission wouldn’t require advanced systems for recycling water and air; Orion’s should be good enough.

The group also wrestled with the problem of communicating with a spacecraft more than two million miles from home. “At even a near-Earth asteroid, you’re 10 voice-seconds away,” says Korsmeyer. “You’re not really conversing with Earth at that point. The whole nature of the interaction becomes like the old ship-to-shore communications, a fancy telegraph, a voicemail. Not in real-time.”

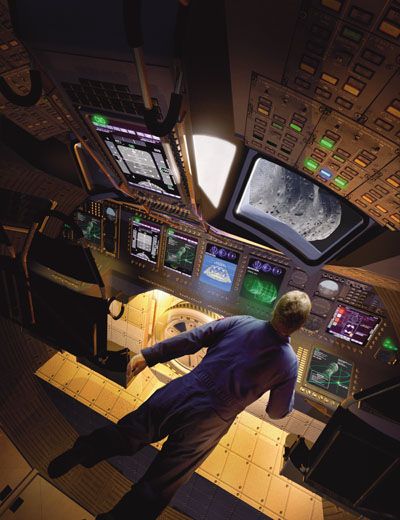

An asteroid-bound crew would therefore need to “bring mission control on board,” says Korsmeyer, in the form of highly automated decision-making software. “When something bad happens, which tends to happen quickly, the crew and systems will have to manage it on their own. This is something humanity hasn’t done yet. But that makes it the best of all possible testing grounds for Mars, which, without an asteroid mission, will be like jumping into the deep end without practicing in the shallow end.” In comparison, “the moon is like the baby pool. I don’t mean to minimize that—Apollo 13 showed us you can drown there too.” But, he says, an asteroid “would really be someplace fabulously new. You’re talking 2.5 million miles, more than 10 times the distance between Earth and the moon. You’d be so far away you could cover up Earth with your finger. It would be no more than a beautiful, pale blue star.”

The 2006 NASA study didn’t go into detail about what astronauts would do once they reached an asteroid. But results from Japan’s robotic Hayabusa mission, which in 2005 investigated the near-Earth asteroid 25143 Itokawa up close, have led to some intriguing speculations.

“Itokawa was one of the most heavily researched asteroids—radar, visible, infrared,” says Paul Abell, a scientist on contract with NASA from the Planetary Science Institute who participated in the Advanced Projects Office study. “Many countries and collaborators had studied it. But when we got there with Hayabusa we were surprised by what we saw.”

It turned out to be a rubble pile loosely held together by its own gravity. “It’s a sandbox,” Abell says, “about 40 percent porous. Lots of empty space, like you have in a jar full of marbles. That was a really profound discovery.”

The first asteroid to be explored by humans might look a lot like Itokawa. While scientists are reluctant to name a specific target when the mission hasn’t even been approved, two candidates tend to crop up on lists of NEOs that would be reachable in the next two decades. A tiny one called 1991 VG—just 40 by 14 feet, or about one-seventh the size of Itokawa—comes around in the year 2017, but is probably too small to be of interest. A more likely candidate, 1999 AO10, is the size of a football field. It could be reached in 2025, long after Orion starts flying. Both missions would require a round trip of 150 days.

“We really don’t have a ‘best one,’ ” says Abell. “It’s far too early in the time line to select a target.” Besides, scientists find new asteroids all the time. “Hopefully we will have many more [choices], and get to know them a little better than we do now.”

Although Ed Lu has left NASA, he hasn’t gone far, and his Mountain View, California office is just down the road from Korsmeyer’s. Lu took a job last year with an advanced projects group at the headquarters of Google, where the former astronaut is dreaming up technologies that will go beyond Google Maps and Google Earth. He thinks of it as Google’s version of the Lockheed Skunk Works.

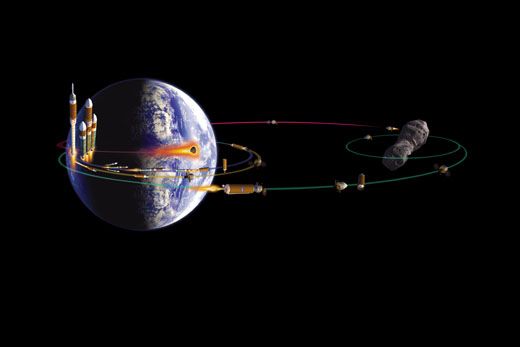

Lu says there are two basic ways to reach a NEO. An optimal target would have an orbit similar in breadth to Earth’s, but inclined, so that it would cross the plane of Earth’s orbit at a point not far away. Such an object would come around every six months.

Orion would fly out to meet the asteroid at its first plane crossing, stay with it for half a year, then come home when the asteroid crosses the plane again on the opposite side of the sun.

“You hop on,” says Lu, “and hop off six months later.” The payoff: less fuel required.

The other option—a shorter mission of up to, say, four months—would rendezvous with the asteroid as it approaches Earth, ride it home, then hop off. Or, hop on as it passes Earth, ride it for a few weeks, and hop off in deep space, requiring a return trip of several weeks to a couple months. This type of mission demands more fuel, but would open the field to a greater number of target asteroids.

None of these missions requires more time in space than the six months astronauts typically spend on the space station. A Mars round trip requires three years. Lu’s own return after six months of weightlessness was easy, he says. Having spent two hours on aerobic and strength training every day in orbit—“and we did it religiously”—he was able to stand up on the Kazakh plain immediately after landing there in a Russian Soyuz capsule. “I was 70 percent normal within a few days, and 90 percent within three weeks,” he says.

In other words, one of the big unknowns about a Mars trip—how the human body will react to three years of weightlessness—is no concern at all for an asteroid mission. And once they reach their destination, the astronauts won’t have to adapt to one-third Earth gravity, as they would on the surface of Mars. Amid all the discussion of “hopping on and off,” Lu makes a key point. “People get the misconception that we’ll land on an asteroid,” he says. “We won’t. It’s almost zero-G. You’re not going to walk on that surface.” Working around an asteroid would in some ways be like floating around the space station, which is also the size of a football field. Astronauts would likely perform asteroid “walks” using jet backpacks or tethers, possibly firing small anchors into the surface for leverage.

What about the cramped nature of a six-month voyage inside Orion, with a habitable volume only one-fifth that of the space shuttle? Lu shrugs it off. “If I knew I was going out to an asteroid and back, I’d live in something half that size. You ask around the Astronaut Office who wants to go. You’ll have a line out the door.”

That comes as no surprise to Bob Farquhar, a former mission designer for such robotic spacecraft as NEAR Shoemaker, Messenger to Mercury, and New Horizons to Pluto. He’s now a fellow at the National Air and Space Museum. “I don’t doubt you’d have guys volunteering to climb inside Orion for six months,” he says. “You could get astronauts who’d volunteer for a one-way mission to Mars. But that’s not the way we do it.”

In the Asteroid Underground, Farquhar is something of an elder statesman and is known for his outspokenness. Having taken part in a recent feasibility study for the International Academy of Astronautics that looked at different options for moving beyond Earth orbit, he doesn’t like the idea of making do with existing Constellation hardware for a stripped-down asteroid mission. “You’d need a transfer vehicle,” he says. “Something big and roomy. And you don’t want it in low Earth orbit all the time.” Instead, he would park an interplanetary, or inter-asteroidal, transfer vehicle at the L2 libration point, about a million miles outside Earth’s orbit, where the gravitational pulls of the sun and Earth are balanced. The transfer vehicle would pick up the crew members in Earth orbit, take them to an asteroid (or, someday, Mars), and then, at journey’s end, return them to Earth orbit.

However the missions are designed, astronauts who travel to an asteroid will spend months outside Earth’s magnetic field, which shields space station crews from harmful space radiation. An asteroid-bound ship would need heavy shielding: perhaps a water or hydrogen jacket, or thick plastic composites. Another unknown, and another technology to develop.

Despite such challenges, the Asteroid Underground has won converts, in part due to a lack of enthusiasm among many in the space advocacy community for NASA’s current plans to return to the moon. Farquhar has been among the most vocal critics. “We need to reexamine this whole lunar thing,” he says. “I think you could skip the lunar landing and lunar bases. They’ll eat up NASA’s budget for the next 50 or 60 years.” In fact, the price tag for an asteroid mission would almost certainly be less than the cost of a lunar landing.

Farquhar was one of 50 thinkers who attended an invitation-only workshop at Stanford University last February, sponsored by the Planetary Society and titled “Examining the Vision: Balancing Science and Exploration.” The group included scientists, aerospace executives, space advocates, NASA staff, and former astronauts. Press reports prior to the meeting made it sound like the Asteroid Underground planned an insurrection against NASA’s lunar program. That led agency administrator Mike Griffin, who has fought to win support in Congress for Constellation, to lash out against those who would push destinations other than NASA’s approved next step, the moon. The controversy may explain why, instead of arguing strongly for an asteroid mission, the statement that came out of the workshop merely called for sustained human exploration to Mars and beyond, which would be done via the moon and “other intermediate destinations.” The word “asteroids” was never mentioned.

Farquhar calls the statement “wishy-washy” and says the meeting was co-opted by NASA attendees. “The Stanford conference didn’t accomplish what [the asteroid advocates] had hoped, which was to take another look at the whole program. The organizers were trying to have an ecumenical experience, inviting people from throughout the industry. There turned out to be more of the faithful than the dissidents. I thought it was a flop.”

For the time being, it seems, the Asteroid Underground has suffered a setback. But the prospect of political change (a new president not wedded to the moon plan), and not just in the United States, gives asteroid mission advocates hope that their fortunes will soon improve. “We might wind up around 2020 with the Chinese about to set foot on the moon, possibly with the Russians,” says Jones. “But we’ll have something else in our back pocket—on our way to an asteroid, we could wave at them down on the lunar surface and say, ‘We did that 50 years ago.’ ”

Dave Korsmeyer has been optimistic about NASA’s interest in asteroids ever since he briefed Constellation manager Jeff Hanley on his study group’s findings in February 2007. “Hanley said, ‘This is great!’ He said the best thing for us to know is that this [Constellation] architecture goes to more than one place instead of just ’round the block.

“Every month since, we’ve been giving a briefing to someone, and not because we’re pushing it. They’re asking for it.” A more detailed study, he says, may be forthcoming.

Rob Landis, a member of the study group with experience in mission control, says, “Apollo 8 was never intended to go to the moon. But NASA said, ‘What if we go anyway?’ That was a huge, quantum leap. I’d say that an asteroid mission is the Apollo 8 of the next generation—before jumping off to Mars, before dipping our toes deeper in that cosmic ocean.”