The Misty Mystique

Over Vietnam, F-100 pilots flew fast and low. Later, they hit the heights.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Misty-Mystique-631.jpg)

In September 1968, a U.S. Air Force pilot, having ejected from his damaged aircraft, took cover in a rice paddy in South Vietnam. The area in which he landed was regularly patrolled by the Viet Cong. Remaining submerged up to his neck, the pilot managed to escape detection until a U.S. military helicopter could lift him from the scene. A quarter-century later, the pilot—Ronald Fogleman—was a four-star general and Air Force Chief of Staff.

In the Vietnam War, downed U.S. pilots were premium currency. For the North Vietnamese, captured airmen were bargaining chips; for the Americans, they were fellow warriors never to be abandoned. Once, however, orders came from a U.S. general in Saigon that a badly injured pilot, lying on North Vietnamese soil, was to be left behind because the rescue effort would conflict with a larger operation. An outraged captain reached Saigon by telephone to demand that someone find out “exactly what I’m to tell the guy on the ground as to why we are pulling out and abandoning him.”

Back at base, the captain sat alone in the bar, cussing out various things, generals not least. A fellow pilot walked in, grinning, to say the downed pilot had been rescued. Apparently, “the general couldn’t figure out what words to use to tell him why we weren’t pulling him out.” The captain who had posed that difficult question was Dick Rutan, a man of varied accomplishments, including a record-setting, nonstop, unrefueled, round-the-world flight in 1986. The aircraft he flew with Jeana Yeager, Voyager, is now on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

At the time, Rutan was a member of an elite group of forward air controllers—which Fogleman later joined—who flew F-100 Super Sabres over the Ho Chi Minh Trail in North Vietnam and Laos, looking for evidence of men and materials moving south toward the fighting. Flying under the call sign “Misty,” the pilots would detect enemy targets, mark them with smoke-dispensing rockets, and guide strike aircraft—usually McDonnell Douglas F-4s and Republic F-105s—in for bombing runs.

The Mistys were a small group: Over the three-year period of the program, from June 1967 to May 1970, only 157 men served as pilots. After the war, many of them became notable achievers. When Fogleman was named the 15th Air Force Chief of Staff in 1994, he replaced Merrill “Tony” McPeak, who had also been a Misty. Two others, Lacy Veach and Roy Bridges, flew as astronauts on the space shuttle, and Bridges later headed NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida and Langley Research Center in Virginia. For his Voyager flight, Rutan received the National Aeronautic Association’s Collier Trophy. Misty alumni include four other generals, a spate of entrepreneurs, a pecan grower, a coffee plantation owner, a sculptor, an evangelical preacher, and 13 colonels.

What accounts for how much Misty airmen accomplished in later years? “Misty was a group of volunteers self-selected from fighter pilots,” says McPeak. “They were bound to be a bit special, so it should be no surprise that many of them turned out well when they eventually grew up.”

Fogleman believes the motivation preceded the mission. “We were fighter pilots in the United States Air Force,” he says. “But ones who wanted to go the next step beyond that. What is it that I can do? What is it that is out there? It was those kind of people—they liked responsibility. They liked hanging it out a little bit. Because somebody had to do it. And the same things that motivate people to achieve leadership positions or be exemplary performers in the military are traits that great CEOs have.”

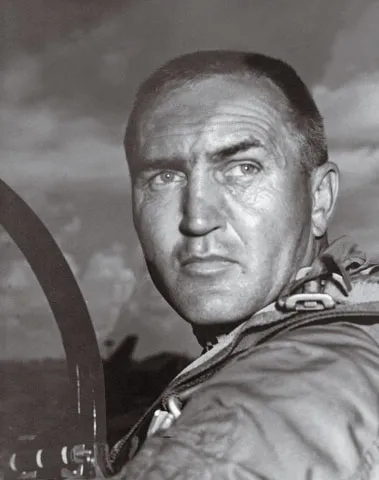

The man who most shaped the Misty program was its first commander, Major George E. “Bud” Day. It was Day who gave the group its call sign, taken from his favorite song, “Misty,” recorded by pianist Erroll Garner. “Misty came about because it was just a great song,” says Day. “I was in Vegas, I think, in the late 1950s the night it was introduced. The guy played it on the xylophone first, then switched over to the piano. He wasn’t a very good singer, but it was such a remarkable song, it brought the house down.”

Day, a Medal of Honor recipient, spent five years as a POW in North Vietnam, where he shared a cell with future Senator John McCain. (In 2004, he appeared with other Vietnam veterans in an ad attacking presidential candidate John Kerry.) He retired from the Air Force as a colonel in 1977. He holds nearly 70 military decorations.

Before the Misty F-100s started flying as forward air controllers, the mission was flown by slow-moving propeller-driven aircraft (the Cessna O-1 Bird Dog and the Cessna O-2 Skymaster), which were getting shot at and, as North Vietnamese anti-aircraft weapons improved, hit with increasing frequency. “Neither aircraft was suitable for a dense automatic-weapons environment,” says former Air Force Historian Richard Hallion.

“After the problem of the slow FACs was recognized, the decision was made by the Seventh Air Force staff to establish the fast FAC,” says Day. “Their recommendation went to the director of operations and then to General [William W.] Momyer. They issued an order establishing what was officially called Project Commando Sabre. I was interviewed by the assistant director of operations and the director of operations for the Seventh Air Force, and ordered to Phu Cat [an air base in South Vietnam] to take charge. I made one recommendation: that we get some of the slow-FAC pilots who could ride in the back and take advantage of their experience as spotters.”

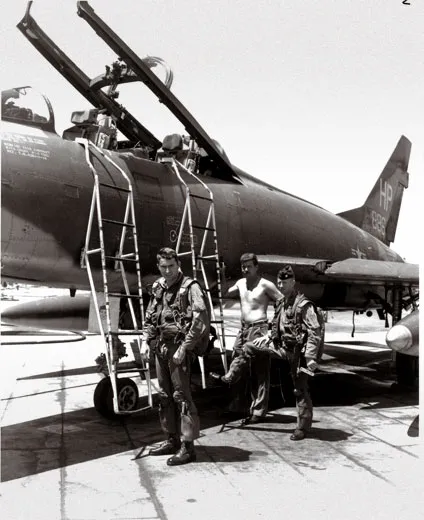

Early on, Day was joined by operations officer Major William Douglass, who had been wounded while flying the O-1 during a previous tour and spent a year convalescing. The pair believed that flying fast and low—perhaps 450 mph at 4,000 feet—offered the pilot the best chance to observe what went on below and to remain safe from anything shooting at him. Officials from the Seventh Air Force decided to use the two-seat F-100F so that the second man, sitting in the rear, could be free to scan the ground, read maps, handle the radios, and take notes. Since nothing in the military long escapes becoming an acronym, the rear crewman became known as the “GIB,” guy in back. Though the term was used more commonly by Air Force F-4 pilots and their weapon systems officers, some Mistys were also familiar with the acronym. “The GIB was along for the ride,” says former Misty James Piner. “He’d call in the coordinates, hoping the dumb son of a bitch up front wouldn’t get him killed.” Pilots new to the unit were assigned to the back seat for their first five or 10 flights, as an orientation. After that, the Misty pilots alternated front- and backseat duties.

The aircraft they flew, the F-100F, was a variant of the North American Super Sabre. “The feel of the F-100 at the working altitude and speed was solid and responsive,” says former Misty Don Jones. “I liked the feel of the controls and the great visibility to see the area near the aircraft.” The F model carried two 20-mm cannon, which could be used for strafing. More commonly, though, the pilots left the ground attack up to the strike aircraft they had summoned, marking targets for them by launching up to 14 white phosphorous smoke rockets, the maximum the airplane could carry.

When the Misty program started, only 16 pilots were on hand to fly the missions. Organizationally, they were a detachment of the 416th Tactical Fighter Squadron, with whom they shared space at Phu Cat, half an hour’s flying time south of the border with North Vietnam. Phu Cat was a village surrounded by rice paddies. On the base, airmen lived in prefab wooden structures that offered window air conditioning and hot showers.

Douglass, who died in March 2012, picked many of the initial pilots. After that, however, most of the unit’s pilots picked themselves. Misty was high risk, and that attracted volunteers who were drawn to challenge and danger. “Pilots wanted to come to Misty so they could fly north of the border,” says Day. “We got people from various fighter wings trying to get hired long-distance. We attracted every studly young guy in Southeast Asia.” For Fogleman, the draw was the mission’s novelty. “It was a new use of a fighter airplane,” he says. “The idea that you could take a jet fighter and put it into a hostile environment and have it survive and increase the effectiveness of the entire fighter force by being there to mark targets for [strike aircraft] that would come in—the whole idea appealed to me.”

After the program got going, the pilots soon settled into a routine, flying four sorties per day (later seven). They started with a before-dawn takeoff; the last flight launched in mid-afternoon. The pilots assigned to the first sortie would rise at 3 a.m., shower, and head to the mess hall for breakfast. At 3:45 a.m., they’d get their flight and intelligence briefing, which included results of the previous day’s missions and the locations of any aircraft losses, studying new intelligence photos and suggested targets for the day, reviewing tanker call signs and radio frequencies, and weather forecasts for North Vietnam.

Once airborne, the Mistys set about looking for targets for the strike aircraft: at the top of the list were supply trucks and anti-aircraft-artillery sites. A key technique was to look for signs of man-made objects in the jungle below. “If you found a square bush, a rectangle, or a circle, that was a target,” says Fogleman, who compares the job to detective work. “And if the water was on the south side of the river crossing, you knew the trucks were moving in that direction. I can remember one particular mission where using that technique, and then flying very low and using sun angle, I was fortunate enough to get the glint off of a windshield of a truck that was camouflaged—there were a bunch of these trucks back there. So we started putting ordnance in there [via the strike aircraft], and we spent the better part of a morning just blowing up trucks.”

“The poor bastard on the ground did not know what things looked like from the air,” says Rutan. “All leaves have a slightly different shade on one side so you’d look for clusters of variegated leaves”—evidence that branches had been overturned for camouflage. Two of the most important attributes for Misty pilots were good eyesight and deductive reasoning. If treetops were covered with a layer of dust, for example, something was happening below those trees.

Misty pilots were impressed by the determination of the North Vietnamese soldiers. “They never gave up,” says Jerry Marks. “We’d take a road away from them in daylight, and they’d take it back by [the next] morning.” Says former Air Force chief of staff Tony McPeak: “We did hand out a lot of punishment, and all Mistys ended up respecting those truckers who stood up so well under heavy air attack.”

It was the Misty pilots’ familiarity with supply-line roads that the strike pilots depended upon, and the Mistys were crucial in guiding the strike aircraft in and out of enemy territory in North Vietnam. “The fighters were sent to our radio frequency for strike control,” says former Misty Don Shepperd, who retired as a major general and head of the Air National Guard and is now a military analyst for ABC radio and CNN. “While they were inbound, we briefed them on target locations, defenses, and best escape routes. When we had them in sight, we rolled in and marked the targets with smoke rockets.”

After the strike aircraft had released their ordnance, Misty pilots flew over the area to see if the targets had been hit; if not, they gave corrections over the radio. “That was our specialty,” says Fogleman. “We could put a smoke down, and we liked to brag that once we put a smoke down, it was always right on the sites, and we’d just say, ‘Hit my smoke.’ But every now and then you used to have to say, ‘See my smoke? Hit 100 yards north of it.’ ” If necessary, they re-marked the targets.

The constant low-level flying was physically and mentally daunting. “We tried to maintain 400 knots and 4,500 feet while looking for targets,” says Shepperd. “We constantly jinked—changed flight direction—and pulled Gs. This was very fatiguing.”

All the jinking was a challenge for the F-100 as well. “The airspeed could not be maintained during the continuous G forces while flying the jink, so we frequently used the afterburner to regain the speed that kept us safe—or safer,” says Don Jones, who flew for the Civil Air Patrol after leaving the Air Force. “Flying the F-100 at the low altitudes meant continuous exposure to anti-aircraft gunfire and even small-arms gunfire. The feeling I felt was exhilaration brought on by the general fear of being hit.”

That fear formalized a few rules: Straight-and-level flight was forbidden, as was flying below 4,000 feet. Pilots were not to engage in second passes. If they missed a target, they let it be until a later return. In November 1968, Kelly Irving ignored that rule, which, he said, is why his military career consisted of one more takeoff than landing. Circling back over a target for a second try, his aircraft was hit. Irving recalled the incident at a 2008 Misty reunion in Oregon, outlining the procedure that pilots were to execute (if possible) after being hit: Level the wings, hit the afterburner for greater thrust, gain altitude, and head for the South China Sea (it was easier to retrieve pilots from the water than from the jungle).

When Irving’s F-100 was hit, his GIB said the pair had to eject. Irving said no way. Moments later, Irving agreed it was time to eject, but this time his GIB voted no. The aircraft reached 23,000 feet, but its hydraulics had been destroyed and Irving couldn’t control it. Losing altitude quickly, the two men bailed out over land. A bit more than an hour later, they were picked up by an HH-53 Sikorsky helicopter, commonly known as the Jolly Green Giant. The helicopter pilot was making his first rescue, and instead of hovering and pulling Irving up to safety, he started flying sideways, with Irving dangling in a rescue harness and dodging tree limbs. Said Irving at the reunion: “I may be one of the few people to get a Purple Heart for having been injured by a tree.”

There were worse fates. Seven Mistys were killed. Four were captured. Thirty-four were shot down, landing either in the South China Sea or in North Vietnamese-held territory.

Do Misty pilots today think the risky missions paid off? “I did control some memorable attacks as a Misty,” says Tony McPeak. “But the fact is, neither Misty nor anybody else succeeded in stopping traffic down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Mission not accomplished.”

Historian Richard Hallion says that Mistys laid the groundwork for future air tactics: “Misty FACs were crucial to the success of strike aircraft operating in high-threat areas where SAMs [surface-to-air missiles], anti-aircraft fire, and possibly MiGs could be encountered. If the absence of the kind of sensors and precision weapons available today limited the results of such attacks, it is still fair to state that the Mistys were the direct forerunners of the F-16 killer scouts used so successfully in [Operation] Desert Storm a generation later.”

In a conflict that brought many no sense of accomplishment, most Mistys believed they were making a difference. One-time Misty commander P.J. White describes his best work as attacks he directed near Quang Tri on a North Vietnamese artillery field that was shelling U.S. Marines across the Demilitarized Zone. Jere Wallace, flying GIB with White, recalls: “We were up before dawn so we could verify the flashes of the guns,” which had a range of 25 miles.

The shelling of the Marines went on for a week, and White remembers waiting patiently for the U.S. strike aircraft to hit their targets. In general, “you couldn’t tell if it was a truck, tank, or tractor that was hit,” says White, who went on to become the first commander of Red Flag, an aerial combat training exercise. In the end it didn’t matter. “We destroyed them,” he says, referring to the artillery that had been attacking the Marines.

There was never any solid measure of how much southward-bound North Vietnamese armament Mistys helped demolish. On one successful mission during the 1968 Tet Offensive, 79 trucks were destroyed, and the pilots believed that such successes would have been more frequent had there not been technical shortcomings involving bombing accuracy and the lack of a capability to operate at night. Whatever the number of trucks or arms destroyed on a mission, the pilots knew that for at least the next day of the war, life for U.S. troops on the ground was safer.

Mark Bernstein writes on American history. His next book, John Joyce Gilligan: The Politics of Principle, a biography of Ohio’s leading postwar Democrat, will be published this fall by Kent State University Press. He wrote about the restoration of the Memphis Belle B-17 (Oct./Nov. 2008).