The Other B-29 Missions

The big bomber’s little-known errands of mercy.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/longshore-flash.jpg)

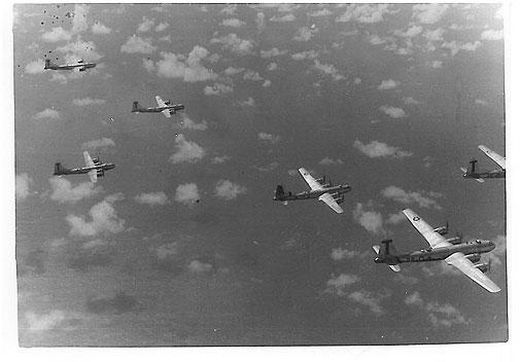

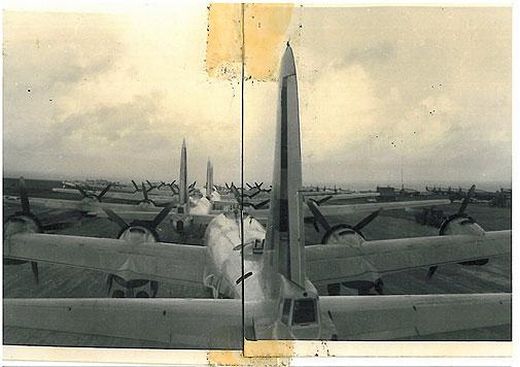

Guy Longshore of LaGrange, Georgia, was a B-29 Command Gunner with the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War 2, and was stationed in the Pacific at the end of the war. On the night of August 6, 1945, unable to sleep, he walked to the edge of the island of Saipan and watched a B-29 bomber take off from the neighboring island of Tinian; later he learned that the bomber was the Enola Gay, headed toward Hiroshima. After Japan’s September 2, 1945 surrender, Longshore was detailed to fly on B-29 missions over Japan, dropping supplies to Allied troops and American P.O.W.s who were still there. He brought along a $12 camera with which he documented the country’s state.

The following is excerpted from his unpublished memoir, “World War II: The Good and the Bad.”

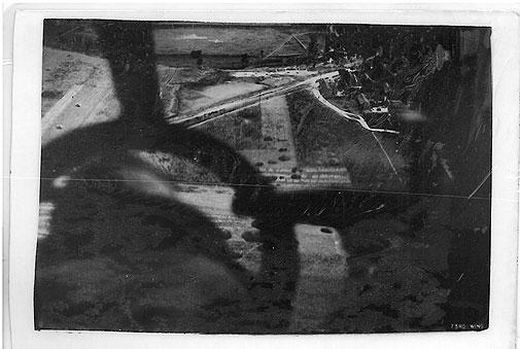

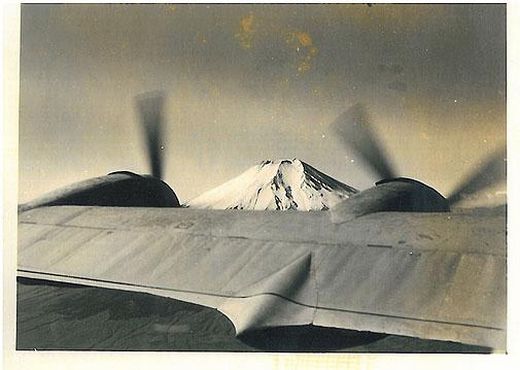

It was not until the war was over and we were returning from a weather mission to Vladivostok (USSR) that I actually saw Japan at a low altitude, and in daylight. It was a total shock seeing the miles and miles of destruction caused by our bombs and the bombs of other B-29s. We were having engine trouble and running low on fuel, so we decided to land at Atsugie Air Field near Yokohama (which is near Tokyo). This afforded us the opportunity to pass over Tokyo at a very low height and speed. I had the rear hatch open and was taking pictures while the bombardier was taking pictures through the nose with the official Air Force camera. After landing at Atsugie we discovered we were only the third American aircraft to land in Japan since the signing of the surrender....

I cannot relate any heroic war stories, nor can I take credit for any good cause I might have been associated with, but the one overwhelming moment of my entire military career was that moment when we first spotted our men in the Japanese prisoner of war camp at Sakata, Japan. First we saw the letters P—W painted in white on the roof of the building; next we saw whitewashed stones spelling out “THANKS 300 MEN” and there they were—skinny, half naked men waving their arms and jumping up and down. I took pictures of all of this, but the original negative is etched in to my brain and is still as sharp today as it was that day in 1945.

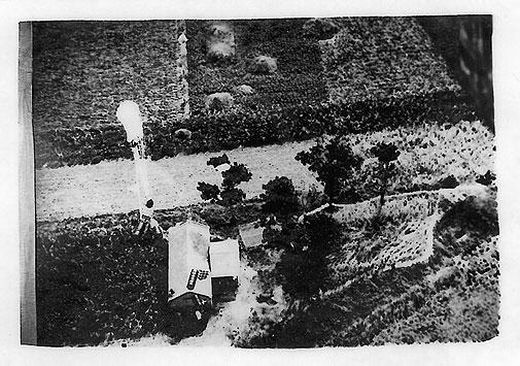

Those P.O.W. missions were a good opportunity for us to see below the clouds; to see the beauty of the countryside as well as the destruction. The Japanese people had viewed B-29s as small specks in the sky for a long time, and I am sure the first time one of our planes passed over their towns at tree top height they were panic stricken. In fact I know they were. I saw a streetcar stop and all the passengers ran for the ditch. A boy riding a bike looked up at us and fell off his bike. The ropes on some of the drums [carrying supplies for the Americans] broke and I saw one drum land on a man, as he stood motionless in the middle of the street. I could see people leaning out of windows and even see the color of the curtains blowing in the breeze. We were low, dangerously low, but we had no way of knowing where the steel drums filled with supplies would land, so we had to fly as close to the target as we possibly could. We flew to other P.O.W. camps, in Fukuoka, Tirar, Yawata, Tokyo, and Higashisome, but the one that stands out in my memory is that first one, the drop at Sakata. Sakata is a small village on the coast facing the Sea of Japan so we were able to make two practice runs over the camp before we actually dropped the supplies; we did not have the hazard of mountains or clouds as we did at some of the other camps.

The Red Cross had furnished us with maps of Japan, but the maps were old and did not show all the mountains or give the altitudes. On one mission we were flying up a dead-end canyon, but our pilot managed to climb out of it just in time; we never did locate that particular camp. The flight to Shanghai is one I well remember. We had one other plane with us and we were to follow him and drop our supplies at the same camp. It took two sweeps over the area before we spotted the camp and at one point we were flying right down the Yangtze River looking out at the downed buildings. The pilots located the camp and both planes dropped their supplies. For some reason, the lead plane turned and started another run over the camp, so we followed. His bomb bay doors were still open, so we figured some of the drums or ropes may have caught and were getting an assist by hand (this did happen more than once since this whole operation of dropping steel drums with small parachutes was a make-shift arrangement). He did indeed drop some more drums, and then we saw a body tumbling out also, and saw the parachute open. When we returned to Saipan we learned that the co-pilot of the lead plane had a brother in that particular P.O.W. camp and he was the one that bailed out to search for his brother.