The Raiders Remember

In an annual ceremony, the last of the Doolittle Raiders recall their part in victory over Japan.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Raiders_Remeber_0911_6_FLASH.jpg)

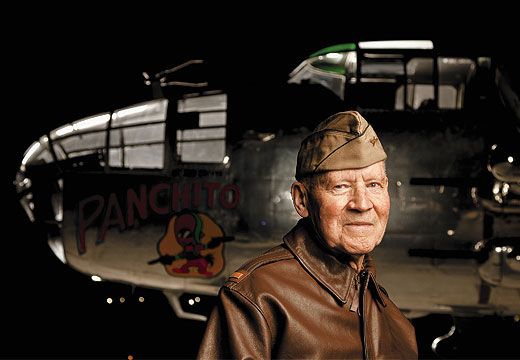

We honor the memory of Dick Cole, the last surviving Doolittle Raider, who passed away yesterday at 103. When we covered a reunion of the Raiders in 2011, Cole recalled the historic April 1942 mission. This story originally appeared in the September 2011 issue of Air & Space/Smithsonian magazine.

DICK COLE IS STILL amazed that the first U.S. combat mission in World War II—a daring daytime raid to bomb Japan using Army Air Forces B-25B Mitchell bombers flying off a Navy carrier—was assembled, trained for, and flown in less than 90 days. “You could never get that done now. It was one of the marvels of Jimmy Doolittle,” says Cole, 96, who was Doolittle’s copilot in the first of 16 B-25s that bombed Japan on April 18, 1942. Though Doolittle, a well-known air racer and accomplished engineer, had a fun side, “he was all business” en route, Cole recalls. “There was no chit-chat.” One reason may have been that all 80 volunteers on the raid knew a crash landing or bailout somewhere in the Far East awaited them at mission’s end: Because a Japanese patrol boat spotted the carrier, the bombers were forced to take off from the Hornet about 250 miles farther back from their intended departure point. There was no guarantee they’d have enough fuel to reach the landing strips in China they had counted on.

As Cole’s airplane passed over Japan, “we could see people waving at us. The Japanese had just had an air-raid exercise, so they probably thought we were part of that.” After dropping bombs on Tokyo, Doolittle flew to occupied China, where the crew bailed out in a night storm and, with the help of friendly villagers, evaded capture by the Japanese.

Cole served 28 years in the Air Force, retiring as a lieutenant colonel. Today he raises “the best weeds in Texas” on his five-acre farm in Comfort. The oldest of five remaining Raiders, Cole plans to attend next year’s 70th anniversary reunion in Dayton, Ohio, where he was born and grew up idolizing Doolittle.

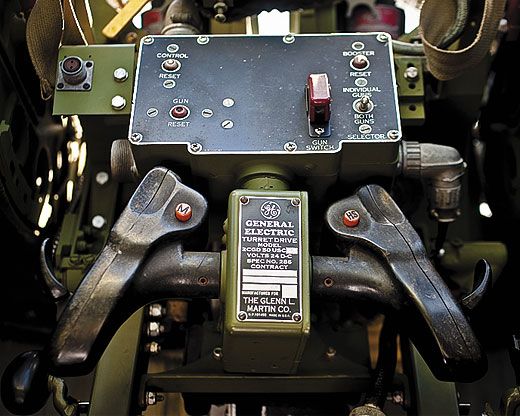

FROM HIS PERCH IN the top turret of the seventh bomber, Ruptured Duck, engineer-gunner David Thatcher never got to fire his .50-caliber machine gun over Tokyo. “I didn’t need to,” he recalls. No fighters challenged the bomber, and although “there was a lot of anti-aircraft fire, it wasn’t very accurate. We were coming in over the wavetops. It was a Saturday, about noon. We could see people on the beach and they were cheering.”

After the aircraft bombed the Nissan steel factory, pilot Ted Lawson, who would later recount the raid in his book Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, headed for China, where he tried to land on a beach. “We were nearly out of gas, and couldn’t get high enough to bail out, so we had to come down anyway,” says Thatcher. In the darkness and rain, the bomber hit the water and flipped over, throwing everyone but Thatcher out through the plexiglass nose. After being briefly knocked unconscious, Thatcher managed to escape from the wreckage, and helped get his injured crewmates to safety—an act that won him the Silver Star, to go along with the Distinguished Flying Cross awarded to each Raider. (Doolittle, who feared court-martial for losing the bombers, was also given the Medal of Honor and eventually four stars. He died in 1993.)

After the raid, Thatcher was ordered to Europe where he flew 26 bombing missions aboard B-26s over Tunisia and Italy, including the first raid on Rome. Unlike the Doolittle Raid, those runs had fighter-escorts, usually Spitfires or P-40s. Discharged in 1945, Thatcher returned home to Montana, got married, and raised a family as a postal carrier in Missoula.

Now 90, Thatcher has made more than 40 reunions, which the Raiders have held annually since 1946, and plans to keep going as long as his health holds out. “I’m still able to mow the lawn and shovel snow in the wintertime,” he says. “It’s great to get together [at the reunions]. It seems like I learn something more about their experiences each time I go.” What helps is that the sponsoring city pays airfare, hotel, and expenses for the Raiders and their escorts, says Thatcher, who has brought his daughter along on recent trips.

THE RAID’S NINTH BOMBER, Whirling Dervish, missed its target: a military factory in southern Tokyo. Its bombs hit the Tokyo Gas and Electric Company next door. “We flattened that instead,” says Tom Griffin, the airplane’s navigator. “We didn’t know we’d hit it until some time later, when the facts came out about the mission.” For Griffin, the raid was just the start of a long war. Rescued after bailing out over China, he returned to combat duty as a navigator on B-26 bombing runs over North Africa and Italy.

On July 4, 1943, a week shy of his 26th birthday, Griffin was shot down over Sicily and taken prisoner by the Germans. “It was a long 22 months,” says Griffin, now 95. “I spent it trying to think up ways to escape. It was our job to keep the Germans busy, so we gave them as much trouble as we could.”

When the war ended, he returned home and opened an accounting office in Cincinnati, Ohio. Because tax time is the busiest period for accountants, he was able to begin attending the mid-April reunions only after he closed the practice in the early 1980s. Two other Raiders attend the reunions: Ed Saylor, an engineer on bomber 15, TNT, and Bob Hite, copilot on bomber 16, Bat Out of Hell, are not pictured. At a final reunion, the last two are to open a bottle of Hennessy cognac from 1896 (the year Doolittle was born) and toast their departed colleagues. Says Griffin: “Dick Cole and I have a big thing going about that, who’s going to be the last. We say it’ll be us and we’ll be having that toast.”

Historians say that although the raid caused minimal damage, it had great strategic impact. American morale, still hurting over Pearl Harbor, soared, and Japan at once saw itself vulnerable to air attack. That impression pushed the Japanese navy to try to capture Midway Island, a decisive loss that heralded Japan’s defeat.